Table of Contents

FOR MY MOM AND DAD,

IRENE AND DICK GRIEST,

WITH ALL MY LOVE

AUTHORS NOTE

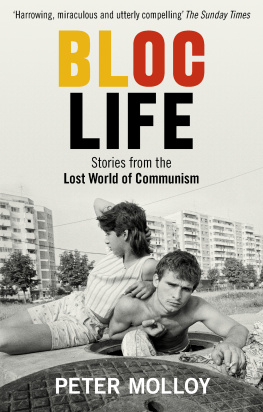

BETWEEN 1996 AND 2000, I visited the following nations: Russia, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, China, Vietnam, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, the former German Democratic Republic, and Cuba. All experimented with communism in the twentieth century, either by choice or by force. None achieved it, but a few are still trying. (I refer to them collectively as the Bloc, although historically, the term referred primarily to the East European nations that formed the Warsaw Treaty Organization.) This book focuses on the capitals of the three that most intrigued me: Moscow, Beijing, and Havana. As cities, they are about as representative of their nations as Washington, D.C., or New York City is of the United States. To truly appreciate the complexities of Russia, China, and Cuba, one must spend time in its heartlands, its rural towns and mountain villagesthe fascinating subject of other books, but not of this.

Translation is a tricky business. I have used a rough English transliteration for the Russian, Pinyin for the Mandarin, and Tex-Mex for the Spanish. My sincere apologies for butchering these beautiful languages as badly in print as I normally do in spoken word.

As for the amazing cast of characters youre about to meet, I have changed the names and identities of mostin some instances to protect their privacy; in others, to ward off possible reprisals. A couple of important characters have been omitted altogether, as per their request. Not all events have been relayed in precise chronological order, and many of the conversations and descriptions are approximations from journal entries and memory rather than formal reportage.

I thank the heroines and heroes of this book immensely for allowing me into their lives and entrusting me with their stories. I can only hope to have portrayed them justly.

PROLOGUE

RED STAR OVER SOUTH TEXAS

THE BAD DREAMS STARTED right before my high school graduation in 1992. Myself at a washed-up twenty-five, roaming Mary Carroll Highs halls in my letterman jacket and getting plastered in the Taco Bell parking lot for fun. I had to get the hell out of Corpus Christi. Wanderlust pumped through my veins: My great-great-uncle Jake was a hobo who saw the countryside with his legs dangling over the edge of a freight train; my dad drummed his way around the world with a U.S. Navy band. I too wanted to be a rambler, a wanderer, a nomadthe kind whose stories began with Once, in Abu Dhabi... or Ill never forget that time in Ouagadougou when _______. Who bought her funky jewelry from its country of origin instead of a booth at the mall.

I only needed to figure out the details: how, where, and with whose money?

Around spring break, an invitation to a national journalism conference for high school students found its way into my mailbox. Having toyed since childhood with the idea of being a reporter, I raised a little money, talked my mom out of her frequent flier miles, boarded a plane for the first time in my life, and headed out to Washington, D.C. The keynote address on opening night was given by a seasoned CNN correspondent who had covered the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. He vividly described how Lithuanians had flung their bodies in front of Russian tanks to shield their television tower, how Estonians had impaled their Soviet passports upon stakes and set them ablaze in protest, how millions spilled into the street and demanded social change. These images and ideas completely transfixed me. The only thing people took to the streets and shook their fists about in South Texas was football.

This mans job would get me out of Corpus!

When his oratory ended, I darted into the aisle, grabbed a microphone, and asked for advice on how to be a foreign correspondent just like him.

He cocked his head and looked straight at me. Learn Russian, he replied. Next question?

Russian? Half my roots were buried beneath the pueblos of Mexico and I could barely say, Dnde est el bao? How could I possibly learn a language like that? And why would I want to? Id never met a Russian, and my primary associations with their nation were the cold war and communism. I didnt know much about either, except that my country had recently won the former and the latter made its practitioners psychotic. (Why else were Soviets always building bombs, Chinese drowning their baby girls, and Cubans crossing shark-infested waters on rafts made of tires and plywood?)

Still, he couldnt have been more specific than Learn Russian. And I had to study some language when I started college that falland I preferred it not be Spanish. My mom had faced such ridicule for her Spanish accent growing up, she never spoke it around my sister and me, to spare us the humiliation of mispronouncing our chs and shs. There hadnt been much incentive to learn it at school, either. Sounding pachuco and acting Mexican were considered insults in my schoolyard back then, conjuring images of an uneducated someone whose jeans hung around their ankles and who had slicked-back, greasy hair. Spanish for me was a language of hushed whispers followed by laughter, of jokes I was never in on, of rosaries and funerals and quinceaeras and weddings, of uncles in cowboy boots calling me mhija and my abuelita in an apron feeding me beans. Moreover, it was the language of the place I wanted to leave. If Russian could get me out, I was willing to give it a try. That September, I enrolled in the Department of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin (UT) and signed up for Russian 601A. That was my first step toward a four-year, twelve-nation tour around the Bloc, but I didnt know it then. When I jetted off to Moscow in January 1996, I was just looking for some excitement. I didnt really care what happened, as long as it was interesting.

SECTION ONEMOSCOW

REVOLUTION IS A DIRTY BUSINESS.

YOU DO NOT MAKE IT WITH WHITE GLOVES.

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov Lenin

1. MOSCOW MANIFESTO

FROM EACH ACCORDING TO HIS ABILITIES,

TO EACH ACCORDING TO HIS NEEDS.

Karl Marx

THEY SAY THE first rule of traveling is packing only what you can carry for half a mile at a dead run. I had every intention of doing this back home in Texas, but my barest essentials filled two huge suitcases and a potbellied backpack. While I could not actually carry all seventy pounds of my luggage, I could push and shove it for small distances. So thats what I did at Sheremetyevo Airport, from passport control to baggage claim to customs. Beyond the exit gate was a mob of onlookers who exuded my first whiffs of Moscow: a scent of equal parts vodka and sausage, leather and tobacco, sweat and strife. For one brief moment, the crowds collective attention focused on me, taking in my lumberjack hiking boots, Michelin man down coat, and wire-rimmed glasses. Inostranka, they murmured my nickname for the next half year. Foreign girl. Then the beefy guys in tracksuits and gold chains turned back to their cell phones, the fashionable girlsimpeccably dressed in floor-length furs, knee-high riding boots, and fluffy hatslit up another round of slender cigarettes, and everyone else resumed their stoic stances. I navigated in, around, and through them and emerged smelling vaguely of sausages.

Next page