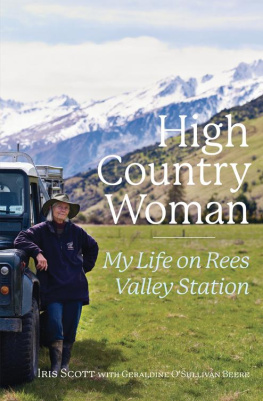

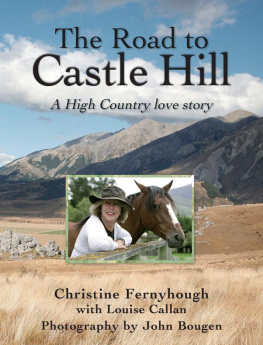

NEW ZEALANDS HIGH COUNTRY farmers are a special breed. They farm in tough terrain, at high altitudes, in areas where extreme climate puts both man and animal to the test. When she was widowed, with three children, in 1992 Iris Scott had to call on all her farming skill and inner strength to carry on as the run-holder of the 150-year-old, 18,000-hectare Rees Valley Station at the head of Lake Wakatipu, near Glenorchy. Not only that, she also had keep up her veterinary practice.

The book also covers the fascinating history of the area long known to locals as The Head of the Lake. It was the focus of North Run, part of William Reess great station based at Queenstown, which was established not long after he and Nicolas von Tunzelman travelled into the area in an epic exploration feat in 1860. Blessed by some of New Zealands most spectacular scenery, the area has long been a magnet for tourists and for filmmakers.

THE NEW ZEALAND FALCON , out hunting, shrieks from the top of a beech tree, kek-kek-kek. Hikers on the Rees-Dart Track, loaded down by their packs, walk the trail along the valley floor thats marked by bright orange marker posts. Far above, a souwester whips snow off the Richardson Mountains and tears it into spindrift clouds. In the valley, a breeze eddies through the tussock. In the bush that skirts the valley, dappled light falls on lime-green moss; the beech trees gently drop their leaves to the forest floor, where robins dart and chitter. At the valley edge, the Rees River races by, pale with powdered schist rock.

I scan the horizon, my eye ranging over the cattle. In this landscape, under my care, is extraordinary biodiversity and complex ecosystems. Its my natural habitat, too, this wide-open space. Its big country, this farm of mine: 18,000 hectares (46,000 acres). On the stations eastern border loom the Richardson Mountains, our undrawn fenceline with the neighbouring station, the Branches, which extends to the Shotover River near Arrowtown.

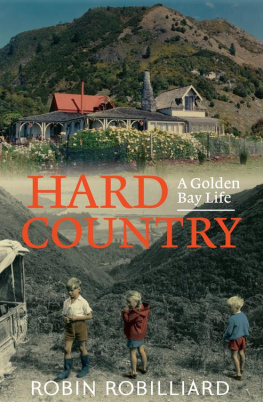

Above the Rees Gorge, all the flat land on the eastern side of the Rees River belongs to Rees Valley Station; all the flat land to the west belongs to Earnslaw Station. The Rees, formed by springs at the head of the valley, gradually expands as tributary creeks feed into it on its journey towards Glenorchy, where it flows into Lake Wakatipu through a wide delta of shingle and schist-sand and knots of willows. Thirty-five kilometres from this delta, at the head of the Rees Valley, is the remote southern wilderness of Mount Aspiring National Park, its brooding, deep-green beech-forested mountainsides and high snow-capped peaks forming the back boundary of the station.

This is a landscape carved by the last ice age, rounded out by glaciers. Scattered through the forest and valleys are boulders of schist, their flanks green and orange with lichen. Some are huge; like a giants plaything, they have been tumbled by the moving ice and then abandoned where they now sit along the forest edges. Isolated moraines some, like Mount Alfred, of very considerable size are all part of the ice ages glacial remains.

If steep crags are one of the natural geological boundaries of the station, then the creeks between the spurs are its major stock boundaries. They run down from each mountain peak, creating a physical border for each of the blocks on the run. Fences? Not in this part of the world. When pastoral farming began here in the late 1860s, fences were built purely to create small enclosures to occasionally hold stock or to protect domestic vegetable gardens. But extensive farming blocks tended to be unfenced on most sides, and on Rees Valley this is still the case today. In any event, fences all too often can be carried away by snow, avalanche, wind and rain. No ordinary farm fence can withstand the punishment.

Rees Valley Station is divided into two blocks: The Farm, which is freehold, and The Run, which is pastoral lease. Each block inside these larger blocks has a name, dating from the early days of human endeavour here. Some, like Invincible or Reef, are reminders of the valleys relatively short-lived goldmining boom in the late 1880s. There are plenty of other echoes of an earlier era throughout the property. Arthurs Creek, for example, is named after Arthur Ford, one of the stations early boundary keepers the men who lived lonely lives in remote huts in the far back country, looking after the stock and keeping a keen eye on weather patterns. As storms loomed, they set out with their dog teams to move the animals back to weather-protected areas. Men rather than fences kept the livestock within the station boundaries.

Im always so keenly aware of the long Pakeha history here. Rees Valley Station was a part of the pastoral run Number 346, granted in 1861 to Robert Campbell. Back then, the run stretched from Twenty Five Mile (or Simpsons) Creek, now on the road between Queenstown and Glenorchy, to Twelve Mile (or Ox Burn) Creek, and included Mount Alfred and all the flat land between the Rees and Dart rivers. The station then passed to John Butement, who held the lease from 1874 to 1887. Next came the Valpy family, who had also left their mark on the station and the district by the time they quit the Rees Valley run in 1895. The Mission Church that they established on the station now stands in Glenorchy, to where it was moved in 1950.

Next was James Dunery, who proved to be a great entrepreneur, not only taking on the lease and the freehold of Rees Valley Station but also running his own carting business, transporting goods to and from the goldmines up the valley. He worked such long hours that they called him night and day Dunery; hed work a shift at the mine, then hitch his team to a wagon and begin carting. His livery and horse stables became the first woolshed on Rees Valley.

Before deciding to let go of the property, Dunery had begun work on several plans, one of which was to establish a new site for the homestead. He moved eight huge fifteen-year-old Wellingtonia trees from the original homestead plot beside Precipice Creek to what is now the driveway to the current house. He also planted what has grown to be a vast holly hedge (more of which later). These days, at the homestead, you cant escape Dunerys legacy: the gigantic Wellingtonia trees tower over the driveway, and the holly hedge that runs along the drive and two sides of the garden is about 2.5 metres tall.

After Dunery came the Scotts, and we have been here apart from an eleven-year gap since 1905. One hundred and seven years with Rees Valley Station: thats quite a number.

THIS REMOTE SOUTHERN LANDSCAPE wasnt always my home and my life. I grew up in the north, in the Auckland suburb of Manurewa, and then at Drury, just south of Auckland. In my early teen years I had become horse-mad, and my parents moved from rural Manurewa to a small acreage what would now be called a lifestyle block, I suppose where there would be space to graze a horse. My family werent country people but somehow I felt that the country was where I belonged.

Growing up, I had, of course, seen photographs of the huge, wild and beautiful places of the South Island. By the mid-1960s I had a chance to actually see them for myself. In 1965, I was one of five women accepted into the Massey University veterinary science degree, which had a requirement for work experience: by the end of the course we needed to have spent six weeks on a sheep farm, six weeks on a dairy farm, two weeks at a meat works, and two weeks at a diagnostic station, and to have completed several weeks practical work in a vet clinic. It made sense; after all, New Zealand was and still is a country whose economy depended on agriculture. Learning about farming was an important part of a veterinarians education.