T HE INSPIRING STORY OF A DETERMINED WOMAN AND AN ISOLATED FARMING LIFE .

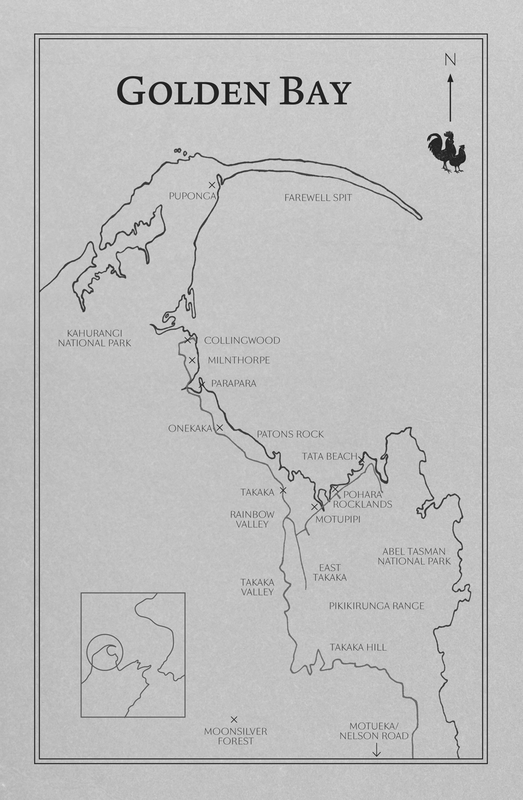

Robby and Garry Robilliard arrived in Golden Bay in 1957 as a young married couple with a baby. They longed to own their own sheep farm, but a lack of money stood in their way.

Then they found Rocklands, a rundown marginal property in the hills above Takaka. Its three previous owners had gone bust; no wonder Robby came to call it nightmare land.

Sixty years on, Robby and Garry still call Rocklands home. Hard Country is Robbys entertaining story of their decades eking out a living at Rocklands, and their encounters along the way with the many and varied Golden Bay characters.

T O G ARRY, MY HUSBAND, AND OUR CHILDREN

T IMOTHY , S ALLY AND M ICHAEL, WITH LOVE .

Contents

The Takaka Hill is my Rubicon. Its the mountainous barrier that isolates Golden Bay, in the north-west corner of New Zealands South Island, from the rest of the country.

What was I doing here?

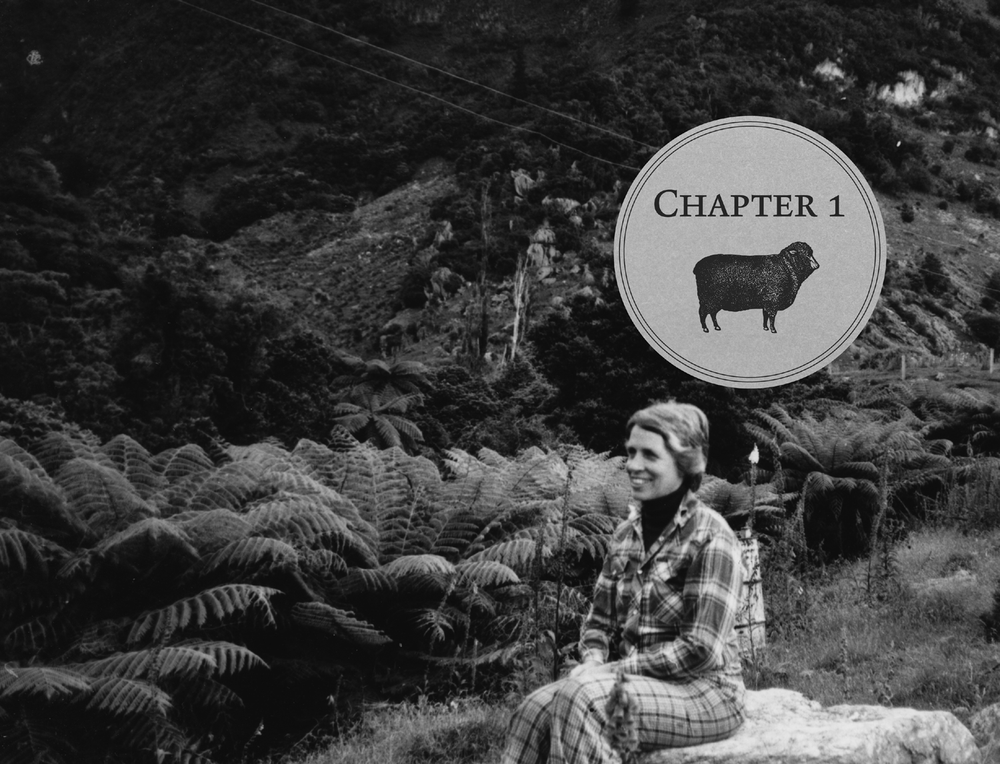

Well, Id married someone as independent as myself. We were not going to work for other people any longer than we had to. And so it was that in 1957, within a year of our marriage, and with a six-week-old baby, Garry and I had taken on what was undoubtedly some of the worst land in the country. Some 1500 mountainous acres of gorse, scrub and bracken, aptly named Rocklands, now belonged to us.

It was all we could afford.

But what a place it was. Rocky slopes rose so steeply they seemed to touch the sky. On the northern slopes of the Pikikirunga Range, our back boundary bordered the Abel Tasman National Park. Sparrow hawks soared at the skyline, the untouched bush thrived, and the beautiful view back down to the ocean took our breath away.

It was wonderful for the soul, but dreadful for farming.

With a slum dwelling to live in, and not a viable fence on the property, we learned the farm had bankrupted its three previous owners. All had been unable to make a living on the unforgiving land.

And so Garry began a lifetime of punishing toil on the land. I simply had no choice but to get on with it as well. If we had given up the struggle, I believe neither of us would have ever recovered from the failure. It was to be an existence that would either make me or break me.

I D BEEN BROUGHT UP IN H AWKES B AY , surrounded by prosperous sheep stations and gracious homesteads. It was a life that had certain rules, certain ways of assessing people.

Were they one of us, or not?

But in Golden Bay, I was to learn, people are judged on what they had achieved in their life. No one here asks, Who was your mother, dear? Its what you do that counts. And extraordinary things happen in this isolated but beautiful region. Outsiders say that the people of Golden Bay are like no one else.

Perhaps its all due to that towering Takaka Hill. Severe boundaries of mountain on three sides and the sea on the fourth meant that, in Golden Bays early years, supplies were brought in by boat, and its produce wool, pigs and butter departed the same way. The first road over the Takaka Hill was built in the early 1900s, replacing the old bridle track with its knee-deep mud puddles. It was improved using relief labour in the 1930s Depression, but even then the new road was hardly a breeze. There is no alternative road out.

I think the isolation made so many of us dig deep into ourselves to find hidden talents, a drive, a focus to do extraordinary things we may never have achieved if wed lived in an easier environment with countless distractions. It has created a close, hard-working community, people who rely on themselves and each other to get through.

Golden Bays first settlers may have named the region for the gold they came to prospect, but once the gold ran out they put in the backbreaking work to carve farms from the bush. By the 1870s the lawlessness of the prospecting days had passed, and the settlers were a self-contained, respectable community with a library, a garden society, several schools and regular musical concerts. Generations of sheep farmers continued to struggle on the rocky hills, with dairy faring better on the fertile pastures on the flats. Much was expected of children as they worked alongside their parents on the land. The courage needed to keep going in the face of poverty and hardship on those desperate hills was immense.

I VE OFTEN ASKED MYSELF, OVER THE LAST almost 60 years in the Bay, where I would have preferred to have spent that large part of my life. There were times, many, when I would have said anywhere but here, but I eventually came to realise that this is the place that suits me. It allows me to be myself like nowhere else I know as long as I can escape sometimes.

And who would ever have believed it possible in 1957, when I first crossed the mighty barrier of the Takaka Hill, aged 23, that I would one day have the opportunity to travel to faraway places as a journalist, giving me a creative outlet and much-needed education, with seclusion once home to get the writing done.

Above all, our tortuous landscape, on which my brave husband slogged out his guts over a lifetime, has proved an ideal environment for our three children to grow up in unspoilt, with character and guts. Im humbled by their work ethic and sense of character.

It took me a while, but I did come to realise that I have been fortunate indeed, not only in my husband, but in the incredible friends we have made, and the life that can be lived in this very beautiful place.

We had driven our ex-army truck, loaded to its gun turrets with our bedraggled worldly goods, through the gate, when I remembered the eggs. Stop! Well have to go back! Weve left the eggs behind!

This was serious. Once wed signed up for a derelict farm in the remote north-west corner of the South Island, Id searched every corner of the pine plantation on the North Canterbury farm which my husband Garry was managing, for eggs from our few hens.

Nine dozen had been preserved in Vaseline as a hedge against initial starvation, as we faced survival as farm owners without the security of wages.

Im not going back, said Garry. Weve said our goodbyes.

Reluctantly I had to agree, but was unable to prevent the tears, caused as much from exhaustion as the egg fiasco. It was only six weeks since Tims birth, which had been a difficult one.

At the time, in 1957, we were both in our early twenties, and for the first year of our marriage wed lived on a prosperous sheep and cattle property in Waipara, an hours drive from Christchurch. The house was a dream. We had free meat and electricity, and a car allowance on top of wages. But we longed for a farm of our own. With us it was an obsession, all the more compulsive because we didnt have the wherewithal to even look at a decent property.

With the arrival of the Saturday newspaper we turned first to Farms for Sale. Anything sounding rough or isolated enough to suit our pockets would find Garry visiting the stock firm involved, trying to look 10 years older, and therefore a better loan risk. But he always received the same answer no and we soon learnt that without sufficient capital Canterburys high land prices were an impossible barrier.

Next page