For Joanne and Belinda, whose unconditional love

has made my lifes journey worth every single step

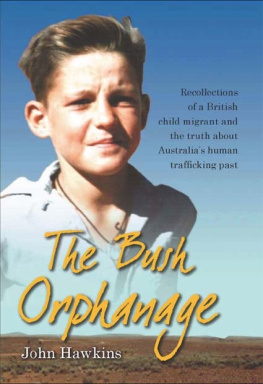

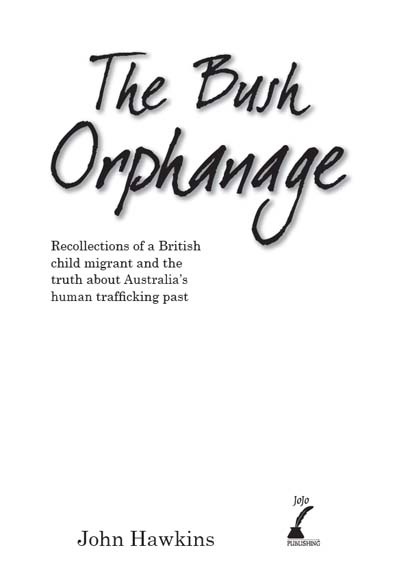

The Bush Orphanage

By John Hawkins

Published by JoJo Publishing

Yarras Edge

2203/80 Lorimer Street

Docklands VIC 3008

Australia

Email: jo-media@bigpond.net.au or visit www.jojopublishing.com

2009 JoJo Publishing

No part of this printed or video publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright owner: JoJo Publishing

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Hawkins, John (John Patrick)

The Bush Orphanage : Recollections of a British child migrant and the truth about Australias human trafficking past / John Hawkins.

9780980619317 (pbk.)

Hawkins, John (John Patrick)

Immigrant childrenAustraliaBiography.

Immigrant childrenGreat BritainBiography.

ChildrenInstitutional care.

Great BritainEmigration and immigration.

AustraliaEmigration and immigration.

304.894041

Editor: Gill Smith

Designer / typesetter: Rob Ryan @ Z Design Media Printed in China by Everbest Printing

Digital Editions Published By

Port Campbell Press

www.portcampbellpress.com.au

ISBN: 9781877006319 (Epub)

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Part I The life journey of a child migrant

1 Baby John

2 Leaving home

3 Great ocean adventure

4 Castledare

5 My Australian family

6 Other lost souls

7 The bush orphanage

8 Tommys class

9 Hunting and trapping

10 Hewats regime

11 Someone at last

12 The bird man

13 The great potato uprising

14 Working boys

15 Becoming a farmer

16 Forced to quit

17 Having another go

18 In search of family

19 Love and dust

20 The highs and lows

21 Settling down with doubts

22 Thats her, thats my mum

23 Settling down again

24 Honesty and dishonesty

25 A loose cannon

26 The aftermath

27 Meeting my other mother

Part II The story of child migration to Australia

Introduction

Early child migration from Britain

Postwar migration

Dealing in children

A policy of institutionalisation

A vastly reduced pool

The role of the Catholic Church

Looking further afield

Who is to blame?

Child welfare reform in Britain

The Curtis Committee Report 1946

The Home Office memoranda 1947

Responsibility for child migrants

The Children Act 1948

A new life of drudgery

The tide turns

The Moss Report 1953

A change of tack

The failed recruitment drive 1955

The widening divide

The Western Australian inquiry 1953

The Ross Report 1956

The British parliament inquiry 1997

The Australian government inquiry 2001

Denial and reparation

Appendix:

The Benhi Karshi orphanage and the Edmund Rice Camp for Kids

Bibliography

Preface

In 1618 one hundred homeless children were taken off the streets of London and sent to Virginia, Britains first American colony. Over the next 350 years an estimated 150,000 children were sent to Britains colonies to work, to populate the land and to defend their new homes.

Remarkably, even into the 1940s, Britain continued to use abandoned children as an arm of foreign and economic policy, responding to pleas from Australia, a faithful wartime ally, to help fill a vast continent of barely seven million people to either populate or perish. The last child migrants, supposedly orphaned or deserted by their parents over 3000 of them were sent to Australia after World War II.

In 1933 Canada banned child migration after years of allegations of cruelty and abuse. Ever mindful of not repeating the Canadian scandal, the British Home Office laid out specific guidelines about how these children should be raised, educated and assimilated into Australian society. However, the more child-friendly and humane model for care of children proposed by the Home Office did not exist at the time in Australia. This could have been a sticking point for the child migration scheme.

A five-page memorandum, written in 1947, from the Home Office to the Australian government, outlined principles of acceptable childcare based on the recommendations of the 1946 Curtis Committee Report, which had condemned institutional care and promoted fostering and adoption. It was accompanied by a one-page memo from the British High Commissioner in Canberra that read, in part, This is a departmental view only and is not to be taken as the view of the British government, effectively allowing Australia to ignore the Home Offices standards of care. It seems likely that the hands of the British Secretary of State, who was responsible for child migrants, were all over this statement, as he fully supported Australias ambitions for child migration.

Ideas about welfare in the two countries could not have been more different. With the passing of the 1948 Children Act (UK), Britain began formally moving away from harsh institutionalised care for apparently abandoned children, preferring to foster or adopt these children back into British society. The Act presented a much fairer social deal for the estimated 30 000 British children who, for years, had been locked away in homes and orphanages. Unfortunately some were allowed to fall through the legal cracks left open by the Act and the Secretary of State.

While British social workers were removing children from institutions, private charitable and religious organisations, with approval from the Secretary of State, continued shoving them straight back into even worse institutions on the other side of the world. Australia had legislated for the care of all British children until the age of 21, but in effect this care only continued until the children were sixteen.

The Australian Immigration (Guardianship of Children) Act 1946 resulted in institutionalisation of all the British children, so preventing them from being fostered or adopted and having a normal home life.

During the parliamentary debate over the Act, the member for Darwin in Tasmania, Dame Enid Lyons, warned of the possible damaging consequences and offered 5000 homes across Australia for fostering and adoptions. Arthur Calwell, the Minister for Immigration, who demanded to retain the personal power of legal guardianship for child migrants, refused, telling the Parliament, We certainly require more safeguards in respect of them than we do for our own children.

During the years of postwar child migration, a frustrated Home Office frequently lectured the Australian government about the inadequacies of institutionalised care. Finally fed up, Britain was forced to ban child migration in 1956 after a withering condemnation in the Ross Report commissioned by the Home Office, citing institutionalised cruelty and abuse.

Part I of this book is the life story of a child traveller cast adrift on an ocean of uncertainties. It is my story.

Part II is a brief overview of the child migration scheme to Australia.

It is a story about the complicity of governments who shirked their legal and moral responsibility for the lives of child migrants and, in doing so, negated the common misconception that the genuine but misguided authorities in Britain and Australia were driven by benevolence and goodwill to give children a fresh start in life. It is also a story of the churches and secular organisations that took part in child migration, and ultimately have taken the blame for the tragedy.

Next page