For Suzanne.

the English also contain pixies. They are enormously solemn, solid and venerable; suddenly there is a sort of rumbling within them, they make a grotesque remark, a fork of pixie-like humour flies out of them, and once more they have the solemn appearance of an old leather armchair.

Karel  apek (trans. Paul Selver), Letters from England

apek (trans. Paul Selver), Letters from England

CONTENTS

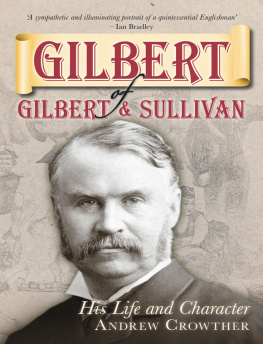

When I tell people that I am interested in W.S. Gilbert, the usual response is a polite, blank look. Of Gilbert and Sullivan, I add, and the eyes fill with recognition. Gilbert tends to be remembered as one half of the indissoluble team: his name on its own means little or nothing. But in his long life he was much more than simply Gilbert-of-Gilbert-and-Sullivan as I explain to people at great length, unless they are lucky.

I believe that there is no such thing as a definitive biography. A writer always selects from the evidence the particular story that s/he wishes to tell, and sets to one side other stories, other equally valid interpretations of the evidence. This book is certainly not intended as definitive. It is intended simply as a version of one part of the truth, going back to contemporary sources wherever possible and paying some attention to some of the things that other biographers may have neglected. I have tried to construct the book as a coherent narrative. This has meant having to leave out many little facts which, try as I might, I could not fit into the jigsaw puzzle. I have tried to eliminate the inaccuracies committed by previous biographers but am aware of the probability that I have introduced some of my own. I can only say that I have done my best.

I have benefited from the help of many people. Firstly, the previous biographers of Gilbert, on whose shoulders I have trodden and whose researches I have shamelessly used: Jane W. Stedman, Michael Ainger, David Eden, Hesketh Pearson, Sidney Dark and Rowland Grey, Edith Browne and others.

I am grateful for the help of many others, who have been generous with their time and expertise. My editor Simon Hamlet should top the list. I wish to thank Ralph MacPhail Jr for his invaluable comments on the manuscript; Brian and Kathleen Jones for hospitality, friendship and scholarship; Sam Silvers, who made us welcome in New York; Arthur Robinson, librarian extraordinary, for unearthing interviews, letters and news stories; Dr Esther Cohen-Tovee for kindly reading my theories about Gilberts character and suggesting when I was going wrong; John van der Kiste for starting it all off; Stuart Box for saving the project at a crucial point; Jane Irisa for pointing out a vital internet resource at exactly the right time; also Vincent Daniels, Hal Kanthor, Simon Moss, Dr J. Donald Smith, David Stone, David Trutt and Marc Shepherd. All errors, misinterpretations of the evidence, ignoring of advice and examples of sheer forgetfulness are, of course, my fault.

I would like to give thanks to the staffs at the British Library, the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the Theatre Collection at the University of Bristol, the Archives at Kings College, London, and Bradford Central Library, for their assistance.

Thanks are due to the Royal Theatrical Fund for their permission to quote from Gilberts unpublished writings, and to Peter Joslin for providing many of the illustrations.

I wish to acknowledge the generous financial assistance of the Gilbert and Sullivan Society and of the Society for Theatre Research in the course of writing this book. Quite simply, I could not have completed the necessary research without their help.

The internet has of course revolutionised the whole business of research. In particular the British Librarys nineteenth-century newspapers website, the University of Florida Collections scans of Fun, and the scanned images of books available at Google Books and at openlibrary.org have been invaluable. Information available at the amazing Gilbert and Sullivan Archive has also been a great help.

Finally, the biggest thanks of all are due to Suzanne, for love and support, and for putting up with the whole business.

One day in the summer of 1891, two men took a tour of the grounds of Graemes Dyke, a large house at Harrow Weald, north of London. One of the men was Harry How, the interviewer at The Strand Magazine. The other was W.S. Gilbert, who had bought Graemes Dyke the previous year out of the profits of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas.

Gilbert 54 years old, tall, grey-haired, moustached and muscular guided Harry How through the walks of roses and sweetbriar, the banks of moss and ferns, the avenues of chestnut trees. He showed him the Dyke itself and the statue of King Charles II standing incongruously on its bank, which had originally stood in Soho Square. He showed him the farm which was also part of the property, with its Jersey cows, its horses, pigs and fowl, and its hayricks. He showed him the observatory, the pigeon house, which the pigeons had not yet been persuaded to use, and the green beehives with bees crowding round, looking, as Gilbert said, like small country theatres doing a tremendous booking.

In the entrance hall there stood a model ship, 16ft in length, built around the mock-up set which Gilbert had had built for the original production of H.M.S. Pinafore in 1878. In another corner of the entrance hall perched two parrots. Gilbert pointed out one of them as being the finest talker in England. The other parrot, who is a novice, he added, belongs to Dr Playfair. He is reading up with my bird, who takes pupils.

Gilbert took Harry How on a guided tour of the building a fine example of Victorian mock-Tudor designed by Norman Shaw. They passed up the oak staircase and into the billiard room, which was decorated with photographs of the Savoy actors in costume, photographs of old theatrical friends and statuettes of Thackeray and Tom Robertson. They visited the drawing room, with Frank Holls dark, brooding portrait of Gilbert presiding over it; the dining room, with its massive Charles I sideboard; and finally the library, with seventy papier-mch heads of Indian types arranged on the bookcases, mingling with drawings by Watteau, Rubens and others. In all these rooms small objets of every sort were arranged on tables, placed on bookcases, hung from the walls. This was a house of things in the Victorian style.

The two men sat in the library and talked. Gilbert talked of his life, his career as a barrister, his work as a man of the theatre:

I consider the two best plays I ever wrote were Broken Hearts and a version of the Faust legend called Gretchen. I took immense pains over my Gretchen, but it only ran a fortnight. I wrote it to please myself, and not the public. It seems to be the fate of a good piece to run a couple of weeks, and a bad one a couple of years at least, it is so with me.

Did he really think that Broken Hearts was a better piece than The Mikado? Few people today, if any, would agree with him. But he routinely disparaged the easy trivialities of the Savoy libretti,

Harry How asked Gilbert if he would write some verses to be published with the interview. We can only imagine the tone of Gilberts voice as he replied: Thank you, very much, but Im afraid I must ask you to excuse me. However, he did allow The Strand to publish a lyric which had not quite made it into The Gondoliers two years before. In it, a young woman pleads with the Grand Inquisitor, who is planning to separate her and her friend from their newly wedded husbands:

Next page

apek (trans. Paul Selver), Letters from England

apek (trans. Paul Selver), Letters from England