FANTASY ISLAND

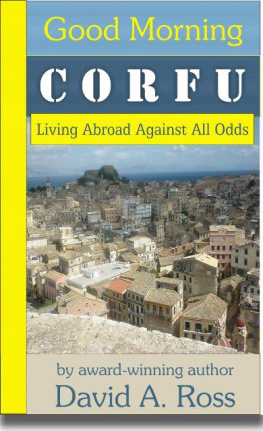

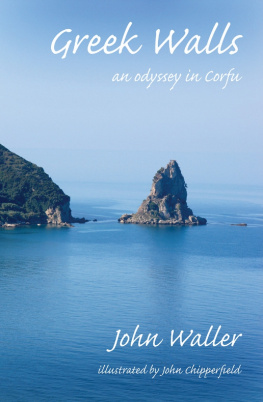

WITH ITS LONG AND VARIED HISTORY, Corfu has played host to many foreigners over the years Italians (Venetians), French and British. These days, over a million travelers per year visit the island, and estimates of ex-pats living here range from fifteen thousand souls on the low side to my own estimate of as many as thirty thousand. What makes Corfu such a compelling place to visit? And what is it about the place that motivates many of those visitors to pull up stakes in their home country and cast their lot on Corfiot soil?

No doubt, the reasons are probably as unique as each transplant. Still, I think there must be a common thread.

I first visited Greece in 1989, Corfu in 1992. As a habitual traveler to Europe (at age thirty-four I began spending every summer away from my home country and traveling for eight to twelve weeks throughout Europe), I came to Greece the first time in an ad hoc way; namely, at the insistence of a traveling companion. I not only fell in love with the sun and the sea, not to mention the cheap prices, but also with the culture. And I still maintain that the hospitality one encounters in Greece is like none other. Back then I often said that even if Greece were not so beautiful, or if it someday became an expensive place to visit, I would come back again and again for the people! After all, where else, upon his return (even after years) is one treated like a long lost cousin, or a returning prodigal?

In 1995, I dared Corfu in winter. After a couple of visits here, and after consulting with a Greek friend who'd recently bought a fair-sized hotel on the Island of Paros for sixty-nine thousand American dollars, I had it in my mind to try to buy a similar hostelry here on Corfu. Arriving by ship at 6:00 oclock in the morning in mid-January was, I readily remember, quite a shocking experience. Once the sun was up, I took the No. 7 bus to Kontokali, but found the village to be something quite different than I remembered from summertime visits. Searching for a room, I walked into the village of Gouvia, which compounded the initial shock, as every shop was boarded up for winter. I did finally find a place to hang my hat, and remained on Corfu for nearly three weeks, asking questions and becoming more and more confused, not to mention more and more convinced that I did not wish to squander the money I'd saved on a tourist hotel on Corfu. Nevertheless, the island held its charm even in winter. I returned to Corfu a number of times in succeeding years before finally deciding to move here in Summer 2001.

Corfu is an easy place to make friends. Anybody who's come here has experienced the acceptance that one receives, try or not. The Corfiots are well experienced at having foreigners in their midst, and the other ex-pats, for the most part, are happy to see a new face. I, too, experienced this acceptance here, so it was easy to feel at home so far away from one's homeland.

Yet, any integration into a new (and very foreign) culture happens by degrees, and mine was no exception. From my eight-year plus vantage point, I must confess that life on Corfu little resembles my perceptions the day I arrived here with my wife, our cat, and a laptop under my arm. The old saying, "Wherever you may find yourself, there you are!" certainly applies. Fact is that what and who you are is maintained (with small but appropriate revisions) no matter where you choose to live, and that's not wholly negative. These days, for me, Corfu is simply my home, with all its quirks and imperfections. Of course I still see its innate beauty, but I must confess that trips to the beach these days are infrequent, the restaurants are a bit repetitive, and the surprises far fewer than they once were.

As I see more and more ex-pats coming to the island to stay, I've often asked myself just what is it, on a personal level, that makes one brave such a move. Knowing well that the reality of living here is inevitably different than the fantasy that brought us here in the first place, I can only conclude that it is some deeper quality that makes one long for island life. Perhaps the inner self must inevitably express itself as the outer reality: Are we each an island unto ourselves, and are some of us compelled to act out that solitary mentality in physical, or symbolic, terms?

For me, the transformation to Greek island life, and from first world competition to a somewhat less hurried lifestyle, has been a success. Not to say that I have not seen many during my five years here who have been unable to make the transition. Still, I can't help feeling that the so-called "island mentality" existed within me long before I came to Corfuto act out my fantasy. Indeed, Corfu (and other like islands) is borne in one's fantasy. The reality, with all its joys and foibles, must prove to be something different, something in and of itself. Of this, I am convinced.

HOW THEY COME AND GO

LIVING IN KONTOKALI, I see quite a few transients during the course of the summer. Of course Kontokali, as a tourist destination, is but a shadow of its former profile. Talk with any of the local people about Kontokalis precipitous decline in tourism, and they are likely to remember a time not long past when the streets of the village were thronged with visitors during summer. Sadly, or perhaps not so sadly, those days seem to be gone.

These days, the one attraction remaining for this once popular tourist village is Gouvia Marina. It is by all accounts a first class facility, so many of the itinerants one encounters in the village have moored their boats and are here for either a long or short stay at the marina. As a result, the tourists, or visitors, one typically finds in Kontokali these days are not week-long package holidaymakers, rather they are the more salt-of-the-earth variety, sailors and those somehow involved in the pastime of sailing. They are quite a colorful lot, to say the least, and if one is fortunate enough to get to know some of these visitors during their stay at Gouvia Marina, he is lucky indeed.

One of the first people I met here in Kontokali, other than the Greeks in my immediate vicinity, was a fellow named Bertie. He was an Irishman who was acting as the skipper of a yacht moored in the marina. Talking with Bertie one afternoon at the Beer Bucket, I learned that he had spent some time living in my home city in the States. We swapped a few stories about Denver while drinking large bottles of Amstel as a toast to each one or so it seemed. As the summer progressed, I met a few other sailors from the marina (DH, an ex-Special Services war horse; OD Alan, a quiet man from the North country; Scottish Jimmie, whom I failed miserably to understand due to his thick brogue) and I fell in with their afternoon drinking crowd (my own thirst, I must confess, was no match for theirs).

Later that summer, however, Bertie abruptly disappeared. Word went out that he'd left rather suddenly for Spain. His departure seemed to me to be a bit premature, so I asked around about it. Apparently, he'd insulted one of the Greek women in Kontokali by making (in jest it was presumed, but not confirmed) a sexual innuendo about the woman's daughter (who was undeniably very attractive). Whatever old Bertie had meant by his off-color comment, innocent or otherwise, the meaning was apparently lost in translation. I'm not exactly sure why he left so suddenly, but I think I can safely assume that his decision was taken with some amount of encouragement from the local Greek population.

That same year, though in late autumn and early winter, I remember another rather colorful figure here in Kontokali. Otto, a Dutchman of ninety-nine, was staying aboard one of the yachts anchored in the marina with his daughter and son-in-law. Otto's ambulatory prowess had apparently long since deserted him, and he was confined to a wheel chair, though that hardly seemed to stop him from getting round the village. (Whether or not his mental faculties were intact is quite another matter altogether). On any number of occasions, I saw old Otto driving his motorized chair down the streets of the village, traffic backed up behind him, with drivers honking and cursing for him to yield the way. Seeming not to hear the car horns (or the explicatives), Otto continued on his way without pause or concern. (Where he might have been going is anybody's guess.) All throughout the winter, he was a familiar (if obstructive) figure on the streets of Kontokali Village.