Contents

Guide

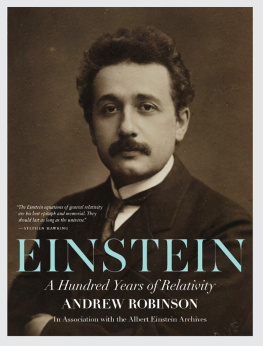

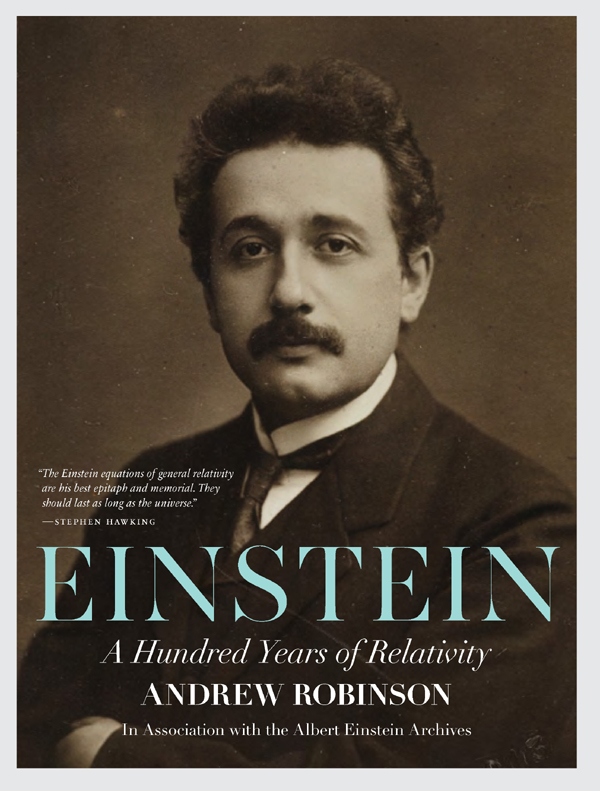

EINSTEIN

A HUNDRED YEARS OF RELATIVITY

Andrew Robinson

In Association with The Albert Einstein Archives

With contributions by:

Philip Anderson, Athur C. Clarke, I. Bernard Cohen, Freeman Dyson,

Philip Glass, Stephen Hawking, Max Jammer, Diana Kormos Buchwald,

Joo Magueijo, Joseph Rotblat, Robert Shulmann and Steven Weinberg

In memory of my father, F.N.H. Robinson,

experimental and theoretical physicist,

who, like Einstein, loved music and sailing.

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

Einstein: A Hundred Years of Relativity was first published in 2005, the centenary of Albert Einsteins most famous discovery. This new and revised edition coincides with another pivotal Einstein centenary: that of his theory of relativity. If the concept of a repeated centenary seems a bit puzzling, let me explain: 2005 celebrated the special theory of relativity, which describes only space and time, while 2015 marks the general theory of relativity, which includes accelerated motion and gravity. Both theories were regarded as too controversial to be worthy of a Nobel prize for many years after their publication. During the past century, however, they have survived all manner of ever more precise experimental tests, in space as well as on Earth, and now form part of the foundations of physics, like Newtons laws of motion.

The book explores just about every aspect of Einstein as a scientist and human being, ranging from his relativity and quantum theories to his political stances and personal relationships, as reviewers appreciatedand this new edition also considers the posthumous publication of Einsteins ideas, thoughts and feelings. The Einstein textual archive is similar in size to that of Napoleon Bonaparte, and several times that of Newton and Galileo. The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, a great scholarly enterprise launched in the United States in 1987 in collaboration with the Albert Einstein Archives in Israel, now runs to fourteen substantial volumes, with separate volumes in English translation, covering Einsteins life up to 1925, and many more volumes to come covering his eventful last three decades, which included his emigration from Germany to America, the Nazi period, the Second World War and the evolution of nuclear weapons. This ongoing research is the subject of a new Afterword, written by the current director of the Einstein Papers Project.

Interest in Einstein continues to increaseand not only among scholars. There are some 1700 individual books about him listed in library catalogues. No other scientist, with the possible exception of Darwin, fascinates the world as much as Einstein. Certainly no scientist is quoted (and misquoted) so often: a point discussed in the fourth edition of a collection of Einstein quotations published in 2011. Even in translation from Einsteins native German, his words mingle inimitable profundity and wit, as is clear from almost every page of what follows this introductory note.

Indeed, I cant resist concluding with a favourite Einstein quotation of my own, an aphorism he wrote for a friend in 1930: To punish me for my contempt of authority, Fate has made me an authority myself. Given Einsteins complexity, it might be rash for anyone to claim to be authoritative about him. But I can confidently say that this book, with its exceptionally diverse and distinguished contributors (three of them Nobel laureates), does bring to life both Einsteins science and Einsteins personality in striking words and images.

______

Hoffmann: 24

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Oliver Craske for conceiving the book and believing in it, and Colin and Pamela Webb of Palazzo Editions for publishing it. Tony Hey, Alice Calaprice, Robert Schulmann and especially Barbara Wolff (of the Albert Einstein Archives in Jerusalem) kindly checked various points about Einstein, including quotations from him and other writers. Dipli Saikia sustained me throughout the research and writing in every possible way.

Andrew Robinson

Palazzo Editions would like to thank Roni Grosz, Chaya Becker, Barbara Wolff and Anat Eban from the Albert Einstein Archives.

PREFACE

by

Freeman Dyson

Albert Einstein's life was full of paradoxes. This book, published in the centenary of his miraculous year, 1905, describes his life and work and personality, all of which were paradoxical in one way or another. Articles written by experts discuss Einstein's views on space and time, chance and necessity, religion and philosophy, marriage and politics, war and peace, fame and fortune, life and death. I am not an expert on Einstein, but I know something about the universe, so I discuss his view of the universe. Einstein's universe was paradoxically different from ours. It had no black holes.

Black holesfirst mooted as far back as 1783 by an English astronomerare familiar objects to today's astronomers. We know that they exist all over our own galaxy and in the central regions of other galaxies. We see them as sources of X-ray radiation emitted by gas as it falls into them and is heated to temperatures of millions of degrees by their overwhelmingly strong gravity. At the exact centre of our own galaxy we see a black hole weighing as much as a few million suns, with massive stars orbiting around it like moths around the flame of a candle. From time to time, roughly once in 10,000 years, one of the moths will fly into the flame and burn. One of the orbiting stars will pass too close to the black hole and will be torn into an orbiting tangle of spaghetti by tidal furces stronger than its own feeble gravity. The orbiting star will die, part of it being swallowed by the black hole and the rest blown away as an expanding cloud of gas and X-rays. Black holes are not rare, and they are not an accidental embellishment of our universe. They are a fundamental driving force of its evolution. They are the dominant source of energy. For every ounce of matter consumed, black holes yield about a hundred times more energy than the nuclear reactions that cause our Sun to shine and our hydrogen bombs to explode. To a modem astronomer, a universe without black holes makes no sense.

To a modem physicist, black holes are also objects of transcendent beauty. They are the only places in the universe where Einstein's theory of general relativity shows its full power and glory.

Here, and nowhere else, space and time lose their individuality and merge together into a sharply curved four-dimensional structure precisely delineated by Einstein's equations. If you were to imagine yourself falling into a black hole, your local perception of space and time would be detached from the space and time of an observer watching you from outside. While you would see yourself falling smoothly into the hole without any deceleration, the outside observer would see you coming to a halt at the horizon of the hole and remaining fur ever in a state of permanent free fall. Permanent free fall is a situation that can only exist by virtue of the distortion of space and time predicted by Einstein's theory. As seen from the outside, you would keep on falling fur ever into the hole and never reach the bottom.

Black holes can also rotate, and the behaviour of space and time as you fall into a rotating black hole is even more peculiar. Rapidly rotating black holes can be a prodigious source of energy. The gamma-ray bursts which we see at a rate of about one per day in remote parts of the universe are the most violent of all natural events; and the most plausible theory to explain them has them originating as instabilities of rotating black holes. All these strange and beautiful features of our universe would have been unimaginable without Einstein's theory to guide our thinking.