Acknowledgements

Having read many history books, Ive often made a point of reading the Acknowledgements, knowing such books do not emerge ex nihilo, but are a research and then composition collaboration of many. Now it is my turn, feeling some inadequacy in trying to demonstrate my heartfelt thanks and gratitude to all who played a part.

Without doubt the first amongst equals is my cousin, Ken Watson, who gave me access to his fathers entire wartime collection. We have talked, laughed and debated constantly to the point of becoming best mates. My thanks to Jill, his wife, for putting up with us.

Andy Wright, my editor, brought unsurpassed knowledge and expertise regarding military aviation history, all delivered with good humour and a necessary directness.

My brother, Rod, did an enormous amount on various online databases tracking down leads related to various people appearing in the book.

Ive had nothing but encouragement and support from Keiths family. His sole surviving brother, Don, and wife Joyce, had me into their home twice, where I conducted oral research while being constantly beaten at cards. Aside from Ken and Jill, there were interviews with Keiths children, Sharon, Dorothy, Wendy, Jaye and Shane, and his granddaughter, Gerowyn. As Keith himself would have said, they are a grand lot.

I have had the privilege of coming to know many of the families who took in Keith during the war. Shirley Ake (ne Hurst) and Marion Gillatt (ne Gibson) both appear in Keiths diary as eight-year-olds. They sent information about the war years and photos, along with information about other families. They are truly my English roses. My thanks to Avril Drakes, too, who helped with stories and photos of her family, the Ruslings.

Ben Blackburn was an absolute gem by providing everything on the Blackburns of Coningsby, including photos of Keith not in the Watson collection. His descriptions of his grandparents ironmonger shop are a highlight of the book.

Peter Mothersill and Gill Mullinar very graciously furnished information (with photos) about their grandparents, Rev Jack and Eleanor Mothersill. Elaine and David Owen provided photos of the Kirkcudbright manse.

My grateful thanks, too, to Bill Gardam Jnr, who shared information about his parents, Bill and Becky Gardam.

Pat Clarke of the Pinner Historical Society helped with aspects of the Sid and May Lowrie story. Alan Sutton of the RAFs Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, RAF Coningsby, greatly encouraged me to follow my desire to tell the stories of the UK families.

The Baskerville brothers Tom, David, Peter and Philip all helped with material about their father Alan (Henry) Baskerville, a friend of Keiths and fellow pilot.

A special thanks to Diana Hecker who provided a wealth of information about her father and pioneering aviator, Sam Hecker. Unfortunately, it was not possible to include all I ended up writing about Sam; he deserves a book of his own.

Many others helped with research: Ann Elliott in Toronto, Michele Collins in Huntsville, Beryl Hartley and Michael Nelmes at the Narromine Aviation Museum, Evon Binney at Toogoom, Peter Scott and Paul Nixon in London, Cameron Willis at the Kingston Penitentiary, and Susan Bell at Lillooet. Kristen Alexander provided crucial information on the Lady Ryder Scheme while encouraging me with my writing. Kevin Bending, author of a history of No 97 Squadron, sent me an invaluable research document on No 97 Squadron aircrew. Tony Brady helped with EATS and Wally Fydenchuk with Camp Borden.

All authors need friends, and every friend does a specific job. Thanks to Bryn and Jean Evans who encouraged me to write the book, then kept following up. Janine McMinn told me to focus on one mans war and not get side-tracked by broader issues. My English friend andZeppelin authority, Ian Castle, offered encouragement, wisdom and, when necessary, frank and fearless advice. Dr Jennie Mack Gray, Chair of the RAF Pathfinders Archive, cast her knowledgeable eye across all my work on the Path Finder Force, challenging and tailoring as needed.

Carol James, my ideal reader, gave me my first full review of the manuscript the perfect blend of insight, critique and correction. My long-time friend, Kerri Setch, brought her Photoshop mastery to restoring damaged photos so they could tell their stories. Nobody does it better. Di Bricknell skilfully worked out what I wanted in order to produce the maps. Cathy Johnstone provided exceptionally helpful suggestions around publishing.

A special word of thanks to Group Captain David Freddo Fredericks, Director History and Heritage Services, History and Heritage Branch of the RAAF. He got in behind me and the manuscript in a very personable way and in so doing demonstrated just how serious the RAAF is in preserving the stories of those who have served in its ranks.

To Denny, Allison and the team at Big Sky, my profound thanks for seeing the value in Keiths wartime story, placing your confidence in me to tell it, and then doing all the hard work to bring it to fruition.

Finally, to my dear wife, Kathy, who has tolerated three of us in the house over the past three and a half years her, me and Keith. She was sensible enough to give me free rein, listening to the research breakthroughs, sharing the triumphs and disappointments, hearing me read excerpts of drafts, and rising and falling with me when I laughed and cried at elements of Keiths story. That said, I think shes hoping Keith will move out at some stage!

I beg forgiveness from anyone I have missed.

The Storyteller

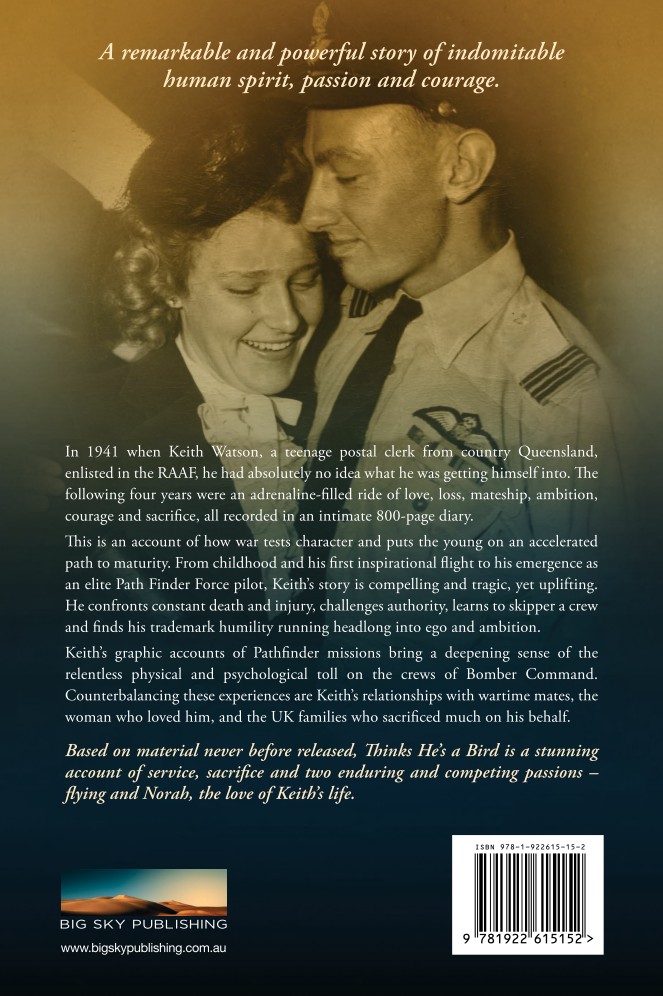

It was January 2004 and Keith Watson had two months to live.

He was being driven north to Burrum Heads with his wife Norah by their daughter Sharon for the annual gathering of the clan. By his own estimation he had been holidaying there for 79 years, except during his wartime service. Given his frailty and the advanced state of his cancer, he seemed surprisingly exuberant and happy, making frequent exclamations about the beauty of the countryside. It reflected his lifelong love of nature, undoubtedly enhanced by the liberal dosage of morphine.

He and Norah would not be staying in the unit at the caravan park as usual, but at one of the several holiday houses the extended family rented throughout the beachside town. The family would gather at Yearenda in Dudley Street, a stones throw from Keiths beloved beach and just around the corner from Travie, his fathers old beachside home, long lived in by his younger brother Don and wife Joyce.

At Yearenda, Keith lounged on the verandah soaking up the scenery. Through the eucalypts with the chattering lorikeets he could see across the cul-de-sac to the white sandy beach, its gently lapping waves long since tamed by Fraser Island. The family was coming and going about him. He was tiring easily, but when the energy came he used it to talk. And what he most wanted to talk about was the war.

This had been an emerging pattern. Four years earlier, after being diagnosed with cancer, Keith took little prompting from his eldest son, Ken, to pour forth recollections of the war years. Unprepared for what he had unleashed, Ken had grabbed the nearest scrap paper and started writing page after page of barely legible script, reflecting the pace at which his fathers memories were arriving. Don and Joyce also recalled that sense of urgency once Keith knew his time was limited. When with them at Travie, the war stories would come, spilling everywhere in no discernible order.

In Keiths final year, as the melanoma metastasized, his chatter had become incessant and repetitive. Sometimes he would reach a point which somehow sent him back to the beginning of the story so he did never ending loops, recalled daughter Wendy.

Next page