This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

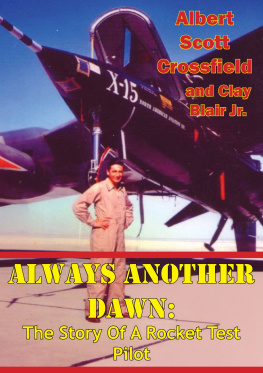

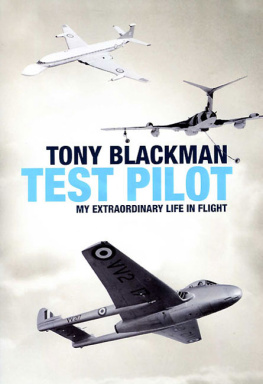

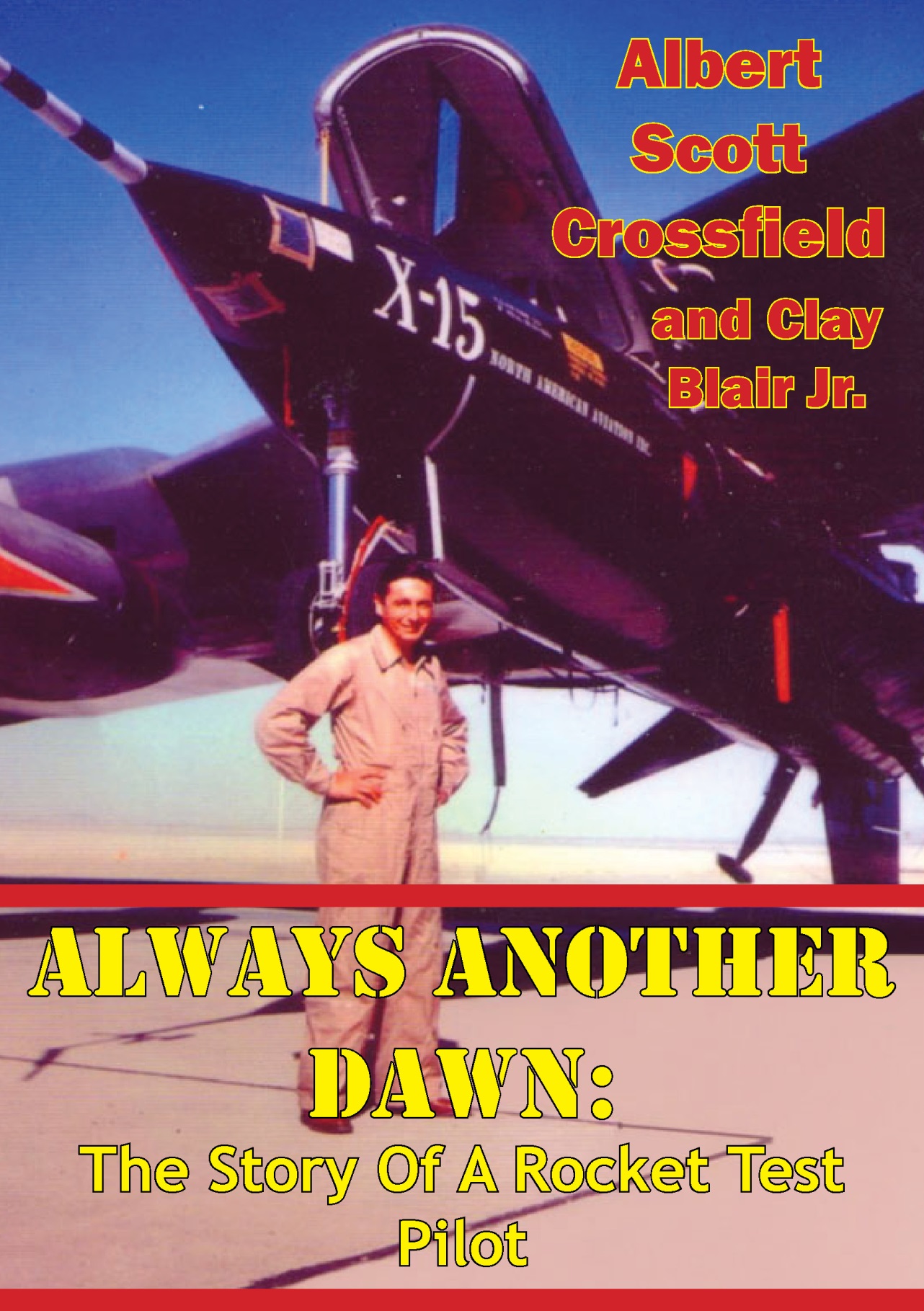

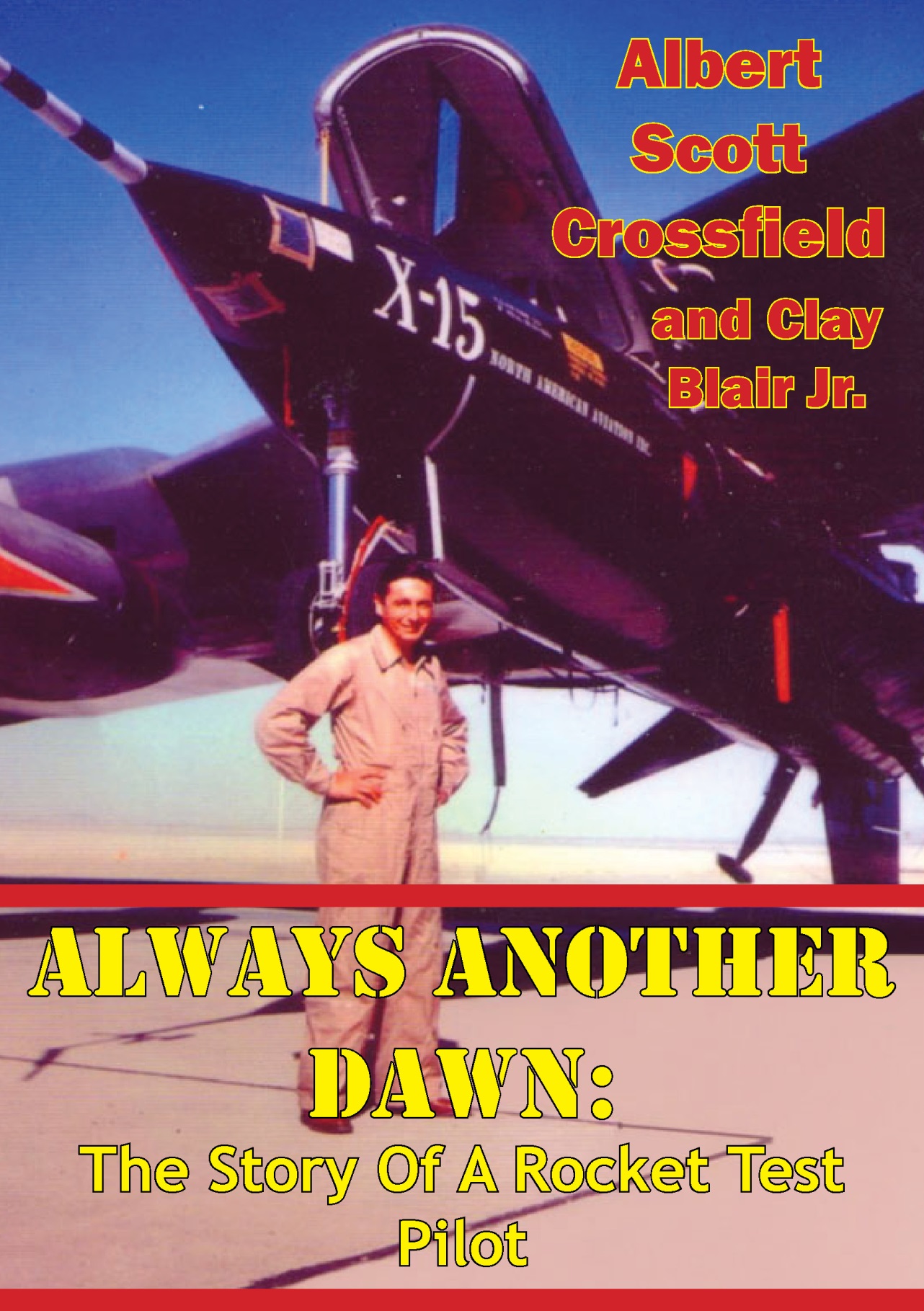

Always Another Dawn

THE STORY OF A ROCKET TEST PILOT

by A. Scott Crossfield with Clay Blair, Jr.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

Dedication

To Joseph, who knows why

Front Matter

All his life Test Pilot Scott Crossfield has carried on a love affair with airplanes. As a child he learned secretly how to fly, and the unyielding ambition to become a superb aviator spurred him to overcome a serious childhood disease. Working for the NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics), Crossfield achieved national renown testing the rocket-powered planes, X-1 and Skyrocket, taking them to amazing heights where man had a new view of his life and the world. He has logged more rocket plane flights than most of the chief test pilots combined.

Written in the tradition of Saint-Exupry and Lindbergh, Scott Crossfield's inspiring autobiography is a testament to the adventure and achievement of the flight pioneers who dare to live beyond the clouds. Why is death the handmaiden of the pilot and how does it feel to face her fifteen miles above the ground? What can a pilot do when fear and panic overtake him? What is it like to be the first man to fly at twice the speed of sound? These are some of the questions Crossfield answers as he explains why he was prepared to devote so much of his time, his dreams, and his aspirations to an experimental plane called the X-15.

When he heard about plans for the X-15, pilot Crossfield knew that his major challenge had begun. For this was to be the first manned aero-spaceship, the first plane to fly at the fantastic rate of six times the speed of sound, and one of America's major bids for supremacy in the race for space. From its very inception the X-15 was surrounded by many challenges: the dictum of some high councils that manned aircraft were already obsolete, unbelievably tough engineering problems, interservice rivalries, and countless dangers. Always Another Dawn tells of the birth of this plane; the daring of the men who painstakingly designed and built her, counting every extra pound a danger and creating innovations unprecedented in flight history. Here is the courage of the men who flew her, their every take-off a hazardous journey into the unknown.

Scott Crossfields belief in the X-15 was his faith in the future of man in space. Probing our new frontier Crossfield experienced fires and explosions, failures and disappointments, and the final triumph of knowing that he had flown a miracle. This book is the thrilling story of mans first faltering steps into space, of the great experiment and the great pilot who set man on his path toward the stars.

Foreword

LONG AGO at Edwards, I heard a story that stuck in my mind. Two small boys, the sons of pilots, were discussing their fathers. One said to the other: Aw, your father cant be a test pilot. He hasnt written a book.

Now I have joined the clan, but, I hope, with a difference. Inevitably I have reminisced, as, it seems, all pilots must. But the intent of this book is broader than mere memoirs. Put simply, the objective is to restate an old principle: that not talk but action is the key to mans progress, and in this age, freedom from enslavement.

A. SCOTT CROSSFIELD Los Angeles, Calif.

August 1960

A Note on Speed

WE HAVE used the modern method of expressing aviation speedthe Mach number. Mach 1.0 is the speed at which sound travels through the air. On an average day at sea level, the speed of sound, or Mach 1.0, is about 760 miles an hour. At higher, colder altitudes on the same day, it is less. For example, at 35,000 feet it might be only 660 miles an hour. Since most of the flying described in this account is at high altitude, Mach 1.0 is, on an average day, about 660 miles an hour. The speed is also expressed in terms of fractions of a Mach number. Thus Mach .5 is half of Mach 1 or half of 660 miles an hourabout 330 miles an hour. Speeds above Mach 1.0 are also expressed in whole Mach numbers and fractions of Mach numbers. For example, Mach 1.5 is the equivalent of one and a half times the speed of sound, or about 1,000 miles an hour. Mach 2.0or twice the speed of sound is twice 660 miles an hour, or about 1,320 miles an hour. Mach 2.5 is about 1,650 miles an hour. Mach 3 is about 2,000 miles an hour.

ALWAYS ANOTHER DAWN

There is no liberty except the liberty of someone making his way towards something. - ANTOINE DE SAINT EXUPRY

CHAPTER 1 A Modern-Day Lindbergh

A MISTY RAIN, typical of Seattle in the spring, fell across the lush green campus of the University of Washington that afternoon. It was 1947. I dont recall the exact date because that whole period of my life remains fixed in my mind as a steady, uninterrupted blur of work and study. I do remember that as I drove through the narrow streets setting apart the ivy-smothered Tudor-Gothic buildings, I proceeded with caution. My car was a veteran of many campaigns in Seattle weather and traffic. It was barely hanging together.

When I pulled into my special parking place behind the Universitys wind tunnel, I was quietly angry. I had just come from an advanced class in aeronautical engineering under Professor Frank K. Kirsten, a brilliant but crotchety old martinet. He had devoted the lecture to a discourse on the jet engine, which, he held, had no future because its fuel consumption was too great. I had challenged his assertions and argued forcibly, concluding, with some heat, that other experts in aviation had made such dogmatic statements, only to have them later completely disproved. Take Monteith, I had said (actually quoting Kirsten). He predicted the cantilever wing would not be practicable.

Yet almost every airplane flying today has a cantilever wing. In the aviation world, as anywhere, I concluded, everything is subject to change. We must believe this.

I walked through the power room to a door marked: Chief Wind Tunnel Operator, stashed my textbook and notes in a desk drawer, and then scanned the bulletin board. Posted over the tunnels Schedule-of-Operations sheet was a photograph of a smashed-up automobile, with Guess Who? scrawled underneath. It was an earlier car I owned, a veteran of several brief but devastating engagements. It occurred to me then, for the first time, that both my problem cars had been painted green. I recalled an old race-track superstition against green cars. That was the trouble, I was sure. Overdriving my car and its brakes in Seattle streets couldnt be the reason, of course.

Next page