Contents

Guide

Page List

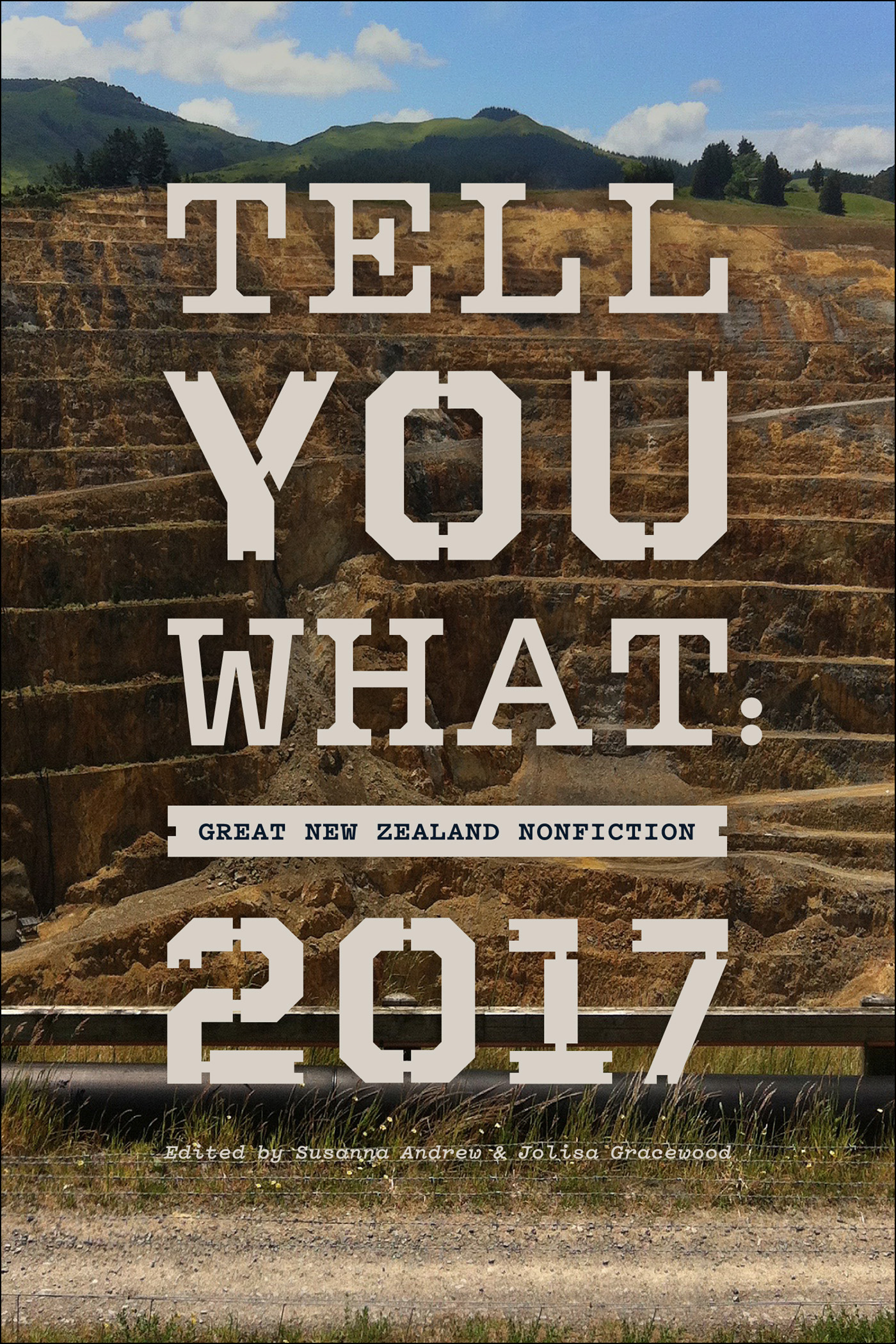

Tell You What

Tell You What

Great New Zealand Nonfiction 2017

Edited by Susanna Andrew & Jolisa Gracewood

Editors note

Fresh voices, new sources, an ever-widening world of great New Zealand nonfiction to select from: this third collection confirms our original intuition that we are swimming in wonderful writing. As John Campbell put it last year: There isnt a single, defining what... There are, instead, multitudinous voices... a true self-confidence, beyond hopefulness and latency, now deep in the bones.

Once again, we dug deep and roamed widely to bring you more of those voices: strong, diverse and confident. Whether pursuing big truths or small, the personal epiphany or the historical revelation, or just taking a topic and running with it, every one of these writers pushes beyond first impressions and easy words towards conclusions that surprised, delighted and moved us.

This is just one decisive slice from a luxurious longlist.We hope it sends you off in pursuit of even more stories from these writers, their peers and the original places of publication. Youll find (as we did) a multitude of lives and minds and histories in flux, writ down with verve and skill for posterity and safekeeping. Tell you what: start here, and dont stop.

David Haywood

Hstens Vemod

A few years ago, I was chatting with another father at a childrens playground in Trondheim, when the subject of hstens vemod came up.

Hstens vemod is a very important Norwegian concept, he told me. Perhaps the most important concept in our entire national psychology. Believe me: to understand hstens vemod is to understand Norway.

He watched as my children circumvented the safety barriers of the guaranteed-safe Swedish-designed playground and climbed precariously on to the roof of the slide tower.

The literal translation of hstens vemod might be something like autumn sadness, he continued. Put simplistically, this is the sadness that you feel in autumn after the summer has passed. There is, of course, nothing wrong with autumn in Norway, it is perhaps our most pleasant season. But after autumn comes the oppressive horror of winter. Therefore we cannot enjoy the pleasures of autumn because of the unpleasant future event that lies ahead.

This, of course, can be extended to Norwegian life in general. How can you enjoy eating an ice cream, for example, when you know that death is inevitable? Dying in a cancer ward, perhaps? Your own death ahead of you like an inexorable freight train about to crush you that is the worst thing. This is why we Norwegians lack confidence; why we cant properly enjoy our vast sovereign wealth funds. Even Frida Lyngstad experiences hstens vemod. Did you know she is Norwegian? People dont warm to her because of her melancholic nature; she is the most depressing member of ABBA.

A long silence followed these words. Neither of us felt like talking. The sun had faded behind a cloud; the playground chilled as a damp gust of wind blew in from the sea. Perhaps this was the first hint of autumn, I thought. Why did I suddenly feel sad?

It is no understatement to say that this conversation has been a profound revelation to me. The hstens vemod of Norway finally put into words an emotion that Ive suffered all my life. Perhaps not so much an obsession with the unavoidability of death, but certainly an Eeyore-ish inability to fully embrace happiness purely as a consequence of the knowledge that, inevitably, all happiness must pass. It may even explain why my enjoyment of ABBA is only 25 per cent that of most other people.

Nevertheless who knows how I somehow manage to struggle on. For the last couple of years my little daughter, Polly, has been a great help with the building work to which fate has sentenced me. At first, I admit, her presence was a bit frustrating. But then she became rather useful: handing me tools, doing simple carpentry work, negotiating improved trade discounts with my suppliers. Eventually she became indispensable. In a few months, however, she will be going to school, and already I am overflowing with hstens vemod at the thought of her departure.

It is a fascinating thing, with your children, to be able to see another persons life a person who is often wholly different to yourself in its full unedited format. Polly has a will of iron. Whereas her older brother had to be cajoled and persuaded (and, in some cases, threatened) through every stage of childhood development, Polly has been grimly determined to overcome every obstacle in her path. Toilet training was over in a flash; she demanded a grown-up girls bed before the thought had even occurred to her parents; afternoon naps were forsaken at the earliest possible opportunity.

It is perhaps only in her difficulty with bedtime that she resembles her brother. For several years Polly was unable to fall asleep except via the mechanism of an extended pushchair ride. There is a great deal of entertainment in the vicinity of our house: cows, sheep, horses, pigs, chickens, alpacas, a church, and a caf where occasional ice creams are eaten. While we trundled along, Polly felt obliged to provide a travelogue of the various sights. Her disembodied voice would drift up from beneath the pushchairs hood.

A streetlight flickering into illumination could provoke an interesting observation: I am a lighthouse. Whenever you push this button, my light goes on. And whenever my light goes on I lay an egg. These are all my eggs. Most of them are for eating, but we have to look after this one because it has a baby lighthouse in it...

The combination of church and caf and a passing police vehicle could provide culinary inspiration: Welcome to my caf. Would you like some steeple pancakes? They are made from church steeples. Dont worry, the church said they didnt mind. And the police gave me some of their special potion that you sprinkle over things to make them good to eat. Your baby could have a bottle? We have real breast milk. It came from my mother who died when I was a baby and all her breast milk fell out. We use the special police potion to make it taste nice and fresh...

As the kilometres rolled by (a 9-kilometre bedtime ride was not unexceptional), Pollys travelogue would gradually begin to fade. Long periods of silence would ensue. As I finally began to hope that our nightly journey was over, her voice would re-emerge sleepily, often with a particularly recondite observation: Gerry Brownlee came along and tried to knock down our chicken house. Then the chickens all got free so they came and pecked his eyes out. He couldnt see so he stumbled around and around. Then he banged into his own house because he couldnt see it. And he knocked his own house down. Ha ha.

This last item touches upon the main source of unhappiness in Pollys life: the government. I suppose that when the government has razed your entire former neighbourhood then you are inclined to view them in a less-than-charitable light. The blind on the window next to Pollys bedroom must always be pulled tight at night to prevent the government getting in; a trip to Christchurch was ruined when a shop clerk mentioned that John Key was visiting the city, and Polly hysterically demanded to be taken home in order to protect our house from government demolition.

![Lt Col C. G. Powles - THE NEW ZEALANDERS IN SINAI AND PALESTINE [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/399129/thumbs/lt-col-c-g-powles-the-new-zealanders-in-sinai.jpg)