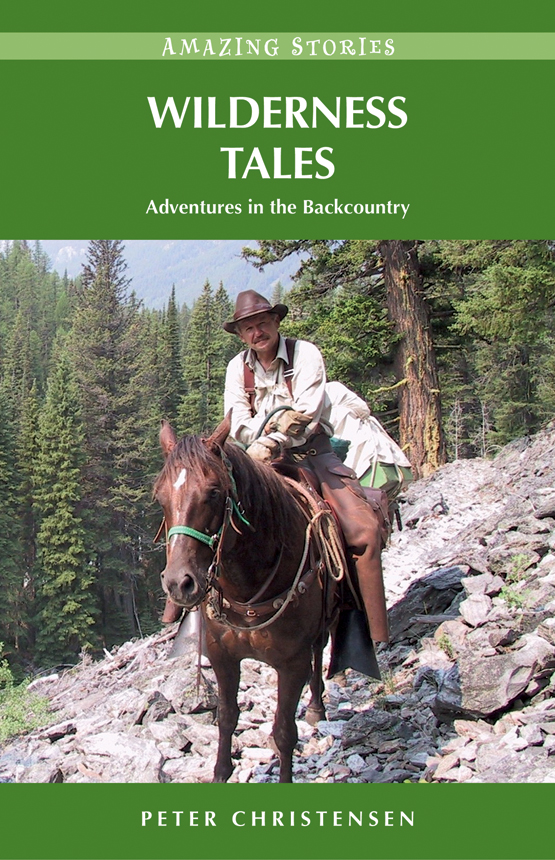

About the Author

Peter Christensen grew up on a west-central Alberta bush farm before the oil rush. He graduated from university and then moved to the wilderness country, where he worked as a guide, a remote area lead hand for Banff National Park, and a backcountry and north coast provincial park ranger. He has published four books of poetry with Thistledown Press. His most recent poetry book is Winter Range , published in 2001.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge and thank the many people who work for the protection and preservation of our wilderness areas.

I also wish to acknowledge the support and love that my wife, Yvonne, has given me. She has travelled many days with me in the backcountry and is a true and fine wilderness companion.

Contents

Copyright 2009 Peter Christensen

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, audio recording or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher or a photocopying licence from Access Copyright, Toronto, Canada.

Published by Heritage House Publishing Co. Ltd. in 2009 in paperback with ISBN 978-1-894974-70-7.

This electronic edition was released in 2011.

e-pub ISBN: 978-1-926936-32-1

e-PDF ISBN: 978-1-926936-54-3

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Edited by Lesley Reynolds

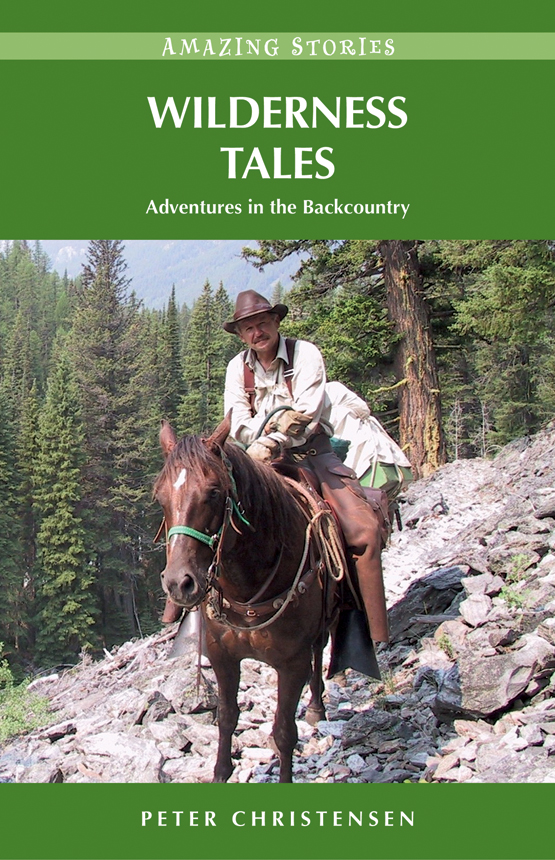

Cover photo of the author at Lower Findlay Creek by Mike Gall

Heritage House acknowledges the financial support for its publishing program from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF), Canada Council for the Arts and the province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

www.heritagehouse.ca

Prologue

As evening approached, Joe and I rode down the back trail of Stoney Mountain on our return from a nine-day shift in the backcountry. As we rounded the belly of the mountain we could at once hear the high-pitched buzzing sound of truck and car tires on the Trans-Canada Highway.

After a shift in the backcountry where the soft thud of horses feet, the twittering of a flock of cedar waxwings or the low moan of a wolf were everyday sounds, this roar of traffic was a stark reminder that we were returning to another time and another world. Hearing the white noise of the highway, I turned in my saddle, grinned at Joe and shouted, Its the sound of civilization!

Joe grinned back, understanding my meaning and the contradictions inherent in the life we led. While working in the protected areas of the backcountry, we were not only insulated from the intrusions of highway noise, but from the stress of modern life. Time slowed down out there. It was as if we entered a different dimension.

Sometimes we would ride for three or four consecutive days to a destination, covering 25 to 40 kilometres of rugged mountain country per day. Time in the saddle had a rhythm of its own, as we constantly searched for signs of wildlife, cut trail and occasionally repacked after long, steep descents. Life progressed at about 5 kilometres an hour.

I threw my gear in the back of the truck and jumped into the cab. I fired up Old Red and eased out of the yard, making a right turn onto the Trans-Canada Highway. After the first kilometre I noticed the traffic whizzing by at an astounding rate; I also noted that I was driving about 70 kilometres an hour.

I have been at this juncture between backcountry and frontcountry pace many times. I take a deep breath, check and adjust my rear-view mirror, straighten up, check my speedometer, pay attention and then get with the traffic. I shift both mechanical and mental gears into high and enter the 21st century of daily hot baths, box-spring mattresses, constant multifaceted stimulus, and Laz-Z-Boy chairs.

CHAPTER

A Horse Named Wasp

During the 1970s and early 1980s, I worked for various guide outfitting operations in British Columbia and the Yukon. After a dozen years of guiding in our spectacular wilderness Crown lands, I decided to make a change and applied for what seemed to me to be the best job in the federal Parks Serviceworking as ranch hand and remote area trail crew in the eastern ranges of the Alberta Rockies. After an intensive formal interview with senior warden staff, a hands-on evaluation by Banff National Park head horseman Johnny Nylund and waiting a year for a job offer, I was finally given a post as Remote Area Trail Crew Lead Hand. A great-sounding title!

Operations for this position were based out of the Banff corrals at the foot of Cascade Mountain. Since I lived in Radium Hot Springs, an hour-and-a-half drive south, I was allowed a spot near the barns and corrals to park my sturdy and comfortable 1962 Safeway camper trailer. As there had been a rash of thefts from the barns and a number of new and expensive saddles stolen, I think they figured having someone camped part-time near the barns was a good idea. This became my spring, summer and early fall base camp for the next five years.

On the trail crew, we worked nine days in mountain backcountry and five days out, from mid-May to mid-October. Typically, my working partner, Joe, and I would buy groceries in Banff Monday evening, have a beer or two at Wild Bills Saloon to compare notes with other park employees and on Tuesday morning head out to the wild and magnificent backcountry of the Rockies front ranges to maintain the trails and remote warden patrol stations in Banff National Park.

Joe and I would return the following Wednesday afternoon and turn our five-horse cavalcade into the home corrals, where they would have all the hay they could eat and a big ration of oats and kibbles once a day for the next five rest days. The corrals were a buggy location during the summer, so despite the rest and bountiful rations, I believe the horses were happy to see us when we returned for the next shift and just as anxious to get out of Dodge as we were.

The Banff district has 16 backcountry warden stations and many hundreds of kilometres of interconnecting trails linking the stations, remote destinations and public campgrounds. Each station is a neat little homestead in the middle of a wilderness paradise, usually consisting of a small, well-outfitted cabin just right for a couple of people, a storage barn supplied during the winter by skidoo with oats and hay, and a corral, all situated near good grazing pastures and a creek. After years of guiding and sleeping on the ground under leaking tent walls in dubious weather, staying in a warm, dry cabin at the end of a days work outside was a welcome relief.

As ranch hands, we provided the support and services necessary to keep the backcountry facilities and trails in shape. In days gone by, wardens used to do this type of work as well as their enforcement and public safety duties, but many of the new 80s wardens didnt like to get dirty or develop callouses on their hands. For many of them, the only sweat on their brows was from spending too many days hunched over computers generating models and predictions based on flawed mathematics. Not necessarily to the wardens liking, in the postmodern age of process politics, the federal Liberals deemed that wardens should spend their time providing scientific data to justify their existence.

From time to time, the chief park warden and his vice-presidents and a few selected businesspeople from Banff would parade the backcountry on a helicopter-assisted Musical Ride, while the old-fashioned-type backcountry wardens made regular patrols throughout the district. When more than a days ride from town, we saw few people. It was our job as remote area trail crew to keep trails cleared, cabins repaired and stocked with split firewood and kindling, barns, corrals and gates functional, and help with packing goods or hauling horses in support of the parks backcountry operations. It was, in the words of an old-timer, good honest work.