For Rob Hosking. For all the tracks you didnt get to tramp, and the book you didnt get to write.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Strategically homeless

Ruapehu

The ice likes to bite

Aoraki/Mount Cook

Blazing a path through ignorance and convention

Kaweka and Kaimanawa ranges

Second-hand socks and snowy tops

Taranaki

Fat girl slim, skeletons and missing men

Arthurs Pass

The mystery of Miss McHaffie

Westland and the deeper south

Pink pyjamas and taking no bullshit

Fiordland

Hidden secrets, missing tribes

Mount Aspiring

Trust your instincts

Conquering fears

Finding home

PREFACE

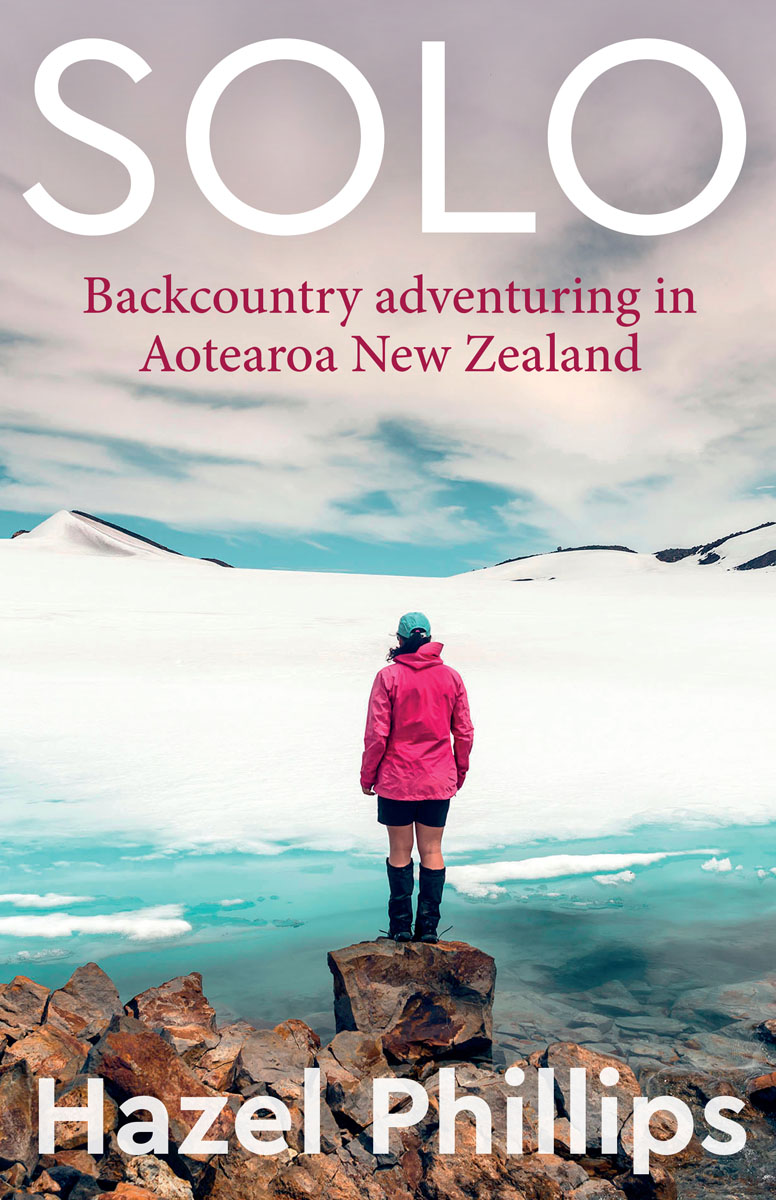

IN PART, THIS BOOK is the story of my quest to find home. Its also about feminism and its intersection with mountaineering.

Perhaps the biggest contrast in mountaineering can be found in the difference between historic climber Freda du Faur, who wrote The Conquest of Mount Cook and Other Climbs, and early author and mountaineer Samuel Turner. Both were admirable climbers in their own right, each with notable firsts. Du Faur was the first woman to summit Aoraki/Mount Cook; Turner, first to solo. Du Faur wrote a book on her climbs, while Turner wrote several. Du Faur emerges as a punchy character, pushing boundaries and bending gender norms, whereas Turner simply comes across as an arrogant egotist.

Having read a number of books on mountaineering, adventuring and wilderness experiences from du Faur and Turner to Peter Grahams biography, Lydia Bradeys Going Up Is Easy and international bestsellers such as Into the Wild (Jon Krakauer) and Wild (Cheryl Strayed) its clear to me that men remain unconscious of their gender as it relates to these activities, while for women it is very much a consideration. Thats not to say that women dwell on the physical aspects (management of menstruation in the wilderness, for example), but more on confidence and ability (or lack thereof), or on the discrimination they experience. Even though women now make up a greater proportion of, say, attendees on snowcraft courses, we still feel othered. Alpine clubs accept women members, there are plenty of women guides so why are we still so astounded to see a woman in the wilderness? At what point do we, as women, not only become normal, but also feel normal?

This book is also about risk and death. Among those backcountry stories I unearthed there are some real tragedies.

A friend commented that while writing this book Id become quite obsessed with people who have perished in the wilderness. My treatment of them may at times sound glib but I trust that any family member of the deceased mentioned who reads this will know that Ive considered this, and the stories of their folk, with the utmost respect and regard.

When you spend a lot of time in the wilderness, and especially when you have a few near-death episodes, you think a lot about how it might end for you. This awareness is nearly always with me and perhaps thats why I take such an interest in these stories. If you, too, are interested, I recommend the two books by Paul Hersey listed in the select bibliography.

Most of all, I think about it in conjunction with the value of these experiences: is it worth it, the risk? Its a question you need to answer each time you go its specific to each activity. Mostly, Id say no, but I know many mountaineers are driven to climb regardless of the risk.

Theres a saying: there are old mountaineers, and bold mountaineers, but no old, bold mountaineers.

Introduction

Strategically homeless

IN 2016, DISILLUSIONED WITH what Auckland had become, I left. I didnt know where I wanted to live, but I figured that packing up and going on the road would at least help me figure it out.

I was also disillusioned with the standard 40-hour-work-week approach of being chained to a desk, and I had switched jobs to a new gig where I was the only staff member in New Zealand. The rest of the company was based in Australia, so I was left on my own to get on with it. My work became entirely doable remotely, and flexibly everything was done with my 13-inch laptop, iPad and mobile phone and eventually it just seemed silly to stay in Auckland, with its housing and traffic challenges. (In the age of Covid-19, it now seems unthinkable, perhaps ridiculous, that we once demanded that people be tied to a specific desk, in a specific office, for a specific period of time each week.)

And so I left. I packed up my whole life except for a tramping pack, boots and ski gear and cut a fast track south.

For the next three years I was strategically homeless. Home became wherever Id chosen to be at that moment. Sometimes it was an alpine club lodge, sometimes a Department of Conservation (DoC) hut, sometimes camping out in the bush or bedding down in a bivvy bag if Id stuffed up and had nowhere to sleep. Sometimes it was a nice hotel in Sydney, when I had to travel for work, which always presented a bizarre contrast of lifestyles; I once spent the night at Rangiwahia Hut in the Ruahine Range, tramped out the next day, drove to Wellington Airport, flew to Sydney and went to bed in a hotel that night.

Strategic homelessness allowed me to be in the hills every weekend and sometimes on weeknights, too. A typical excursion would start on Friday afternoon, when Id haul on my pack, don my boots and walk into the wilderness until Monday morning. Id usually have until around midday before I needed to be back online; thats when my Aussie colleagues would begin to down their coffee and switch on their computers (and, possibly, wonder where I was).

To the casual social media observer, it looked like I was living a dream life always skiing, tramping, mountaineering, with beautiful photos to show for it. What wasnt quite so obvious in the dishonest social construct that is Facebook, was that it demanded more energy, enthusiasm, time management and work than ever. If I stole a chunk of Monday morning tramping out of the bush, it meant a late-night Monday. If I took off camping up a stream bed on Wednesday night, it meant a long Thursday workday. It was a constant juggling act but it was worth it.

Over those years, I tramped my way up and down the country, from the Hump Ridge to Ruapehu and across the Kaimanawa and Kaweka ranges. I destroyed three pairs of boots, two packs and four sets of gaiter straps. Countless packets of dehy food and tasty snacks were consumed. People were met. Land was traversed. Books were read.

During this time I watched my good friend and fellow journalist Rob Hosking fade from the earth after losing his battle with cancer and never getting to do all the things hed planned. His death and these years taught me that you only get one shot at this stuff. Make sure you give it heaps.

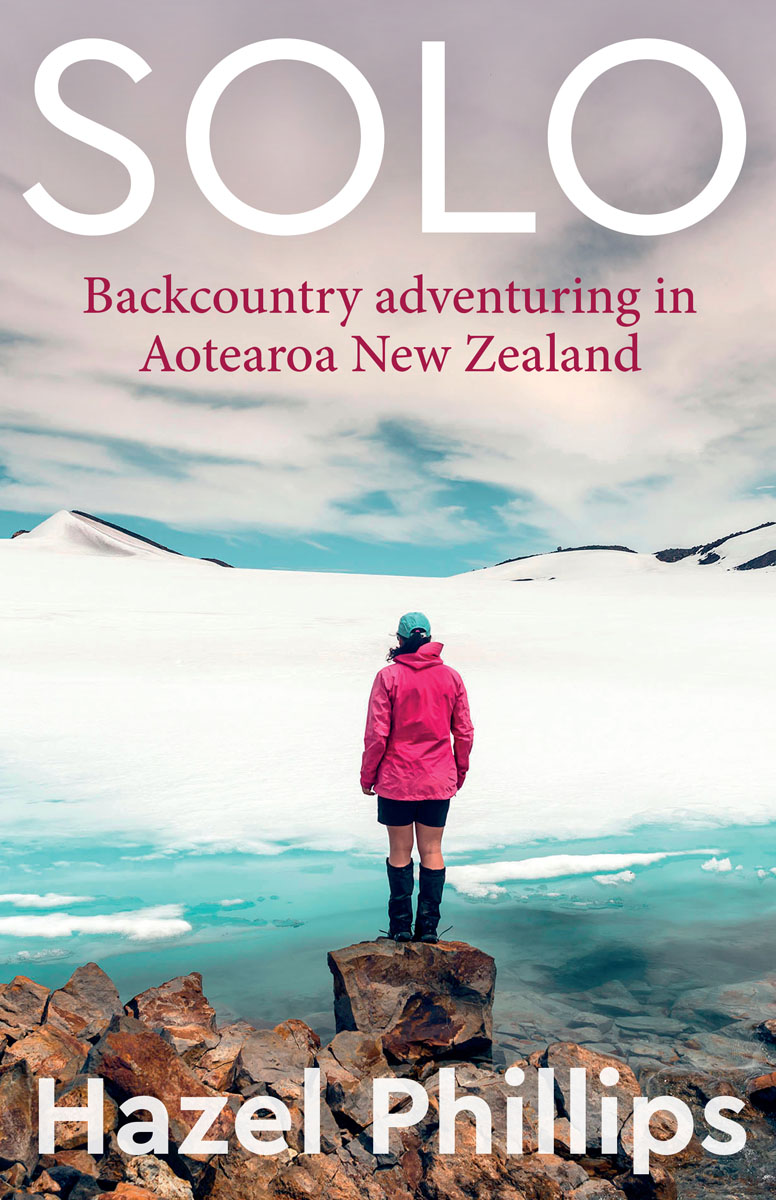

Taking in the stars and snow on a night-time traverse of the Tongariro Alpine Crossing. We started late in the evening under a full moon, which lights up the landscape as it reflects on the snow. It was cold. Very cold. MIKE HEYDON, JET PRODUCTIONS