Contents

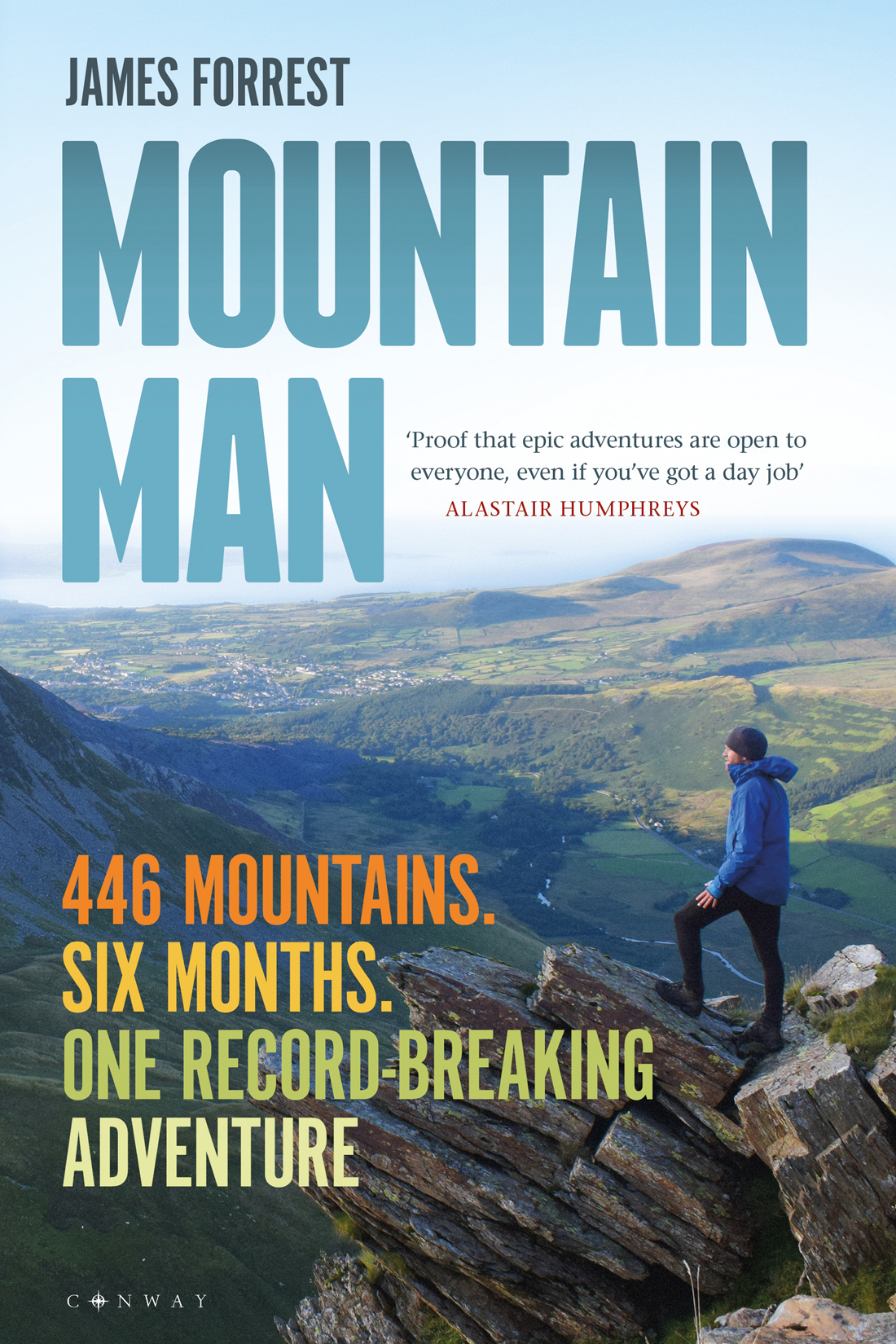

My name is James and there is nothing extraordinary about me. Im not some sort of super-human, all-action adventurer. I have no idea how to abseil down a precipice, or forage for berries, or navigate in mist. I cant build a shelter or tie useful knots or run ultra-marathons. Im scared of most animals and my legs go wobbly if I stand too close to a cliff edge. Dark nights freak me out and I can barely sleep in my tent unless its perfectly horizontal. Oh, and I cant even grow a rugged beard. Rubbish credentials for an adventurer.

There was nothing extraordinary about my adventure, either. I didnt wrestle a bear, or dodge bullets in a war-ravaged country, or survive a near-fatal accident. There were no poisonous spiders or hostile bandits. I didnt triumph over horrific personal demons or have any life-changing epiphanies. I never once had to sever a boulder-trapped limb to free myself from a ravine. All I did was put one foot in front of the other on my days off from work.

But that ordinariness is exactly why my adventure was extraordinary. It proved that you can integrate something truly adventurous into your everyday life. You dont need to be rich, or have 12 months off work, or travel halfway across the world, or be Ranulph Fiennes. You dont need technical skills or expensive kit. With a little outdoorsy grit and adventurous spirit, anyone can go on a big adventure including you.

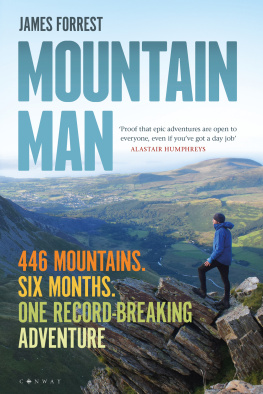

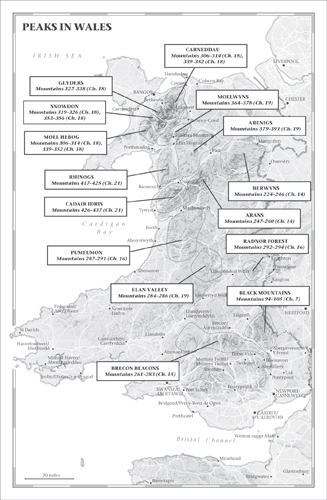

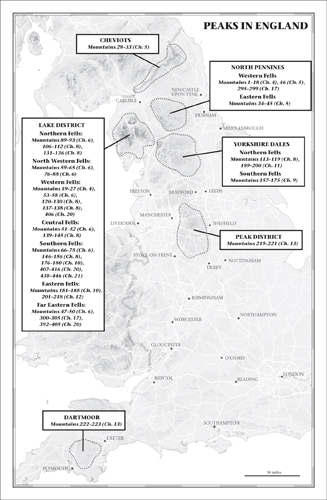

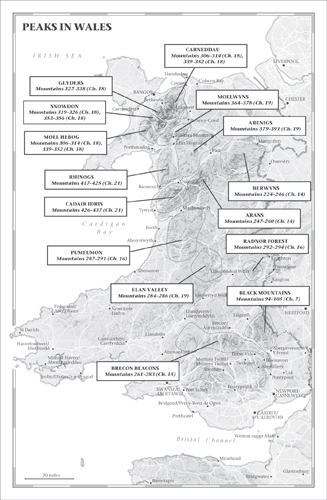

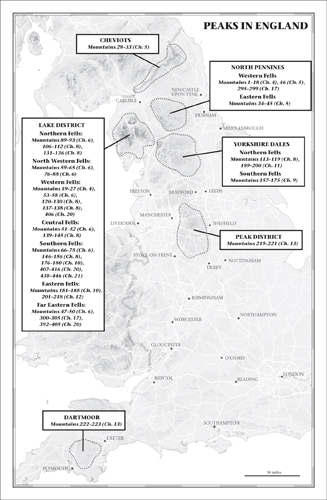

In 2017 I climbed all four hundred and forty-six 2,000ft mountains in England and Wales in just six months the fastest-ever time. Solo and unsupported, I walked over 1,000 miles, ascended five times the height of Everest and slept wild under the stars over 25 times. And I did it all while holding down my job, moving house and, somewhat miraculously, keeping my personal life just about under control.

The mountains taught me a simple but transformative lesson too: if you disconnect from technology, you reconnect with something innate and natural. In an internet-obsessed world of Instagram likes, Netflix binges and bursting email inboxes, we have lost our way. But if you turn off your phone and go climb a mountain, life is happier. Priorities realign, everyday worries dissipate, and closeness to nature and landscape is rekindled. Your reality becomes wholesome, humble, uncomplicated and fulfilling. It is joyous and liberating.

You learn to savour the simple pleasures in life the pitter-patter of rain on your tent, a hot drink on a summit, the stillness of a forest, the wind in your hair, the crunch of the rocks below your feet while simultaneously becoming immune to the stresses and anxieties that plague everyday life. After all, when youre watching the sky swirl a thousand shades of pink as the sun sets over silhouetted mountains, you really dont care about your burgeoning to-do list at work; and when youre hiking along an airy sun-drenched ridgeline, you truly can switch off from the incessant noise of online life; and when youre feeling like the king of the world on top of an exposed summit, you quickly realise how meaningless and fruitless our technology addictions really are.

Conversely, spending time in the mountains is meaningful and fruitful. Every walk Ive completed has been time well spent time for wilderness and solitude, for self-reflection and quiet, for escapism and nature. Every mountain has brought me boundless happiness. To non-believers this might seem a sentimental exaggeration but I stand by the statement. Being in the mountains is good for the soul. Why? Because, in the poetic words of the great fellwalker Alfred Wainwright: I was to find ... a spiritual and physical satisfaction in climbing mountains and a tranquil mind upon reaching their summits, as though I had escaped from the disappointments and unkindnesses of life and emerged above them into a new world, a better world.

So what are you waiting for? Grab your boots, turn off your phone and go explore that better world.

Ive always been pretty terrible at navigation. On countless occasions Ive been well and truly lost in the mountains, wandering around aimlessly, descending into the wrong valley or taking the wrong turn off a summit. One year on the GR20 in Corsica, my friend Joe and I even walked for two full days in the wrong direction, nearly starving ourselves in the process but justifying our schoolboy error with the get-out clause Its all part of the adventure. Back in the mountains of Britain Ive fared little better. Put it this way, if it wasnt for the GPS-tracking capabilities of the OS Maps app, Im pretty sure Id be face down in a gully in the Rhinogs of North Wales right now, with a bemused feral goat nibbling at my rotting body.

My ability to navigate life was, for many years, similarly feeble. I didnt know where I was going or what I wanted. I lost focus of my passions. I made bad decisions. I chased material goals that never satisfied. I marched steadfastly towards one ambition only to realise Id taken a wrong compass bearing and was heading in completely the wrong direction. My journey to the start line of this peak-bagging challenge was, therefore, neither straightforward nor guaranteed. I could so easily have never made it.

I grew up in Birmingham and, despite that fact, had a happy childhood in a loving, middle-class household. My parents gave me everything I could have ever wanted and in return I drove them crazy with what they labelled my ants in pants syndrome. I just couldnt sit still. I always wanted to be outside, exploring or playing football or going to the park. As soon as I could talk, my catchphrase became What are we doing next?

Mum and Dad, understandably, coped with this by shipping me off at every available opportunity to my grandparents down the road in Handsworth. And it was, bizarrely, in that concrete jungle of north Birmingham in the early 1990s that my love for the great outdoors was forged. Every Saturday, my little brother Tom and I, wearing our matching electric-blue shell suits, would be dropped off at Bush Grove and go for a long walk.

Grandpa, who was as tall as a giant and smelled of roll-up cigarettes, would lead the way. He always looked really smart, in a collared shirt, tie, and boots so impeccably polished you could almost see your reflection in them. Granny, with a fresh perm and bubbly demeanour, would take my arm and sync footsteps as we chanted, Left, right, left right, I had a good job and I left her Brummie version of a military marching song that, fittingly, suited her penchant for telling bosses where to stick it. As we weaved along the back streets of Handsworth, through urban parks and past allotments, Tom and I would listen carefully for the roar of the West Bromwich Albion faithful, trying to predict whether it was Bob Taylor or Andy Hunt who had put the mighty Baggies ahead.