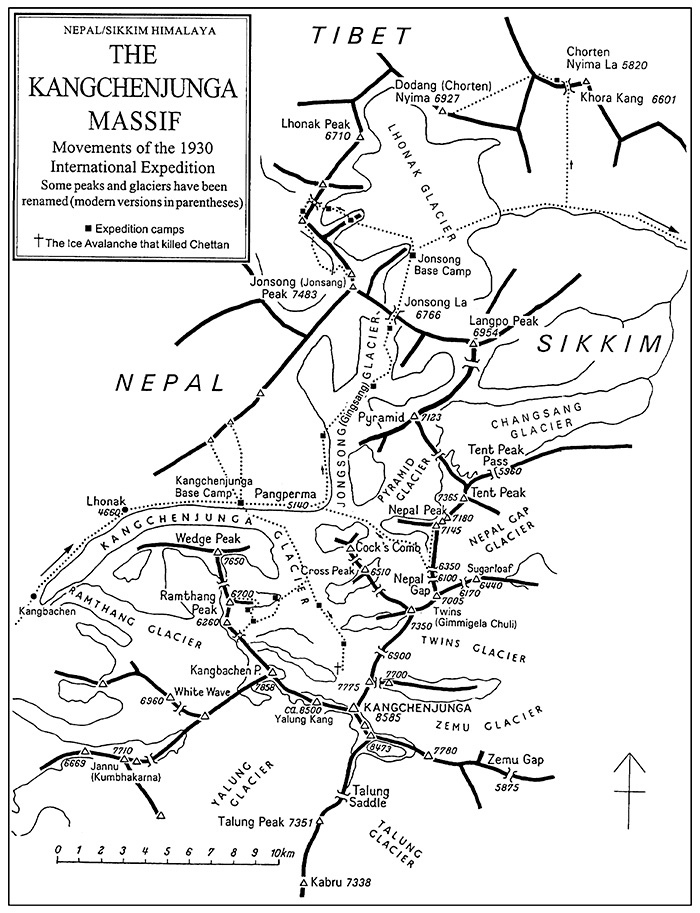

This book is a personal account of the attempt made in 1930 to climb Kangchenjunga, 28,156 feet, and the successful ascent of Jonsong Peak, 24,344 feet, and other great peaks of the Eastern Himalayas, by a party of mountaineers from four nations, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Great Britain, under the leadership of Professor G.O. Dyhrenfurth. I have endeavoured to record my own personal impressions of what was primarily an adventure. It is now no longer necessary to disguise adventure shamefacedly under the cloak of science. The scientific side of the expedition was well attended to, and interesting and important data has been gained. We went, however, to Kangchenjunga in response not to the dictates of science, but in obedience to that indefinable urge men call adventure, an urge which, in spite of easy living and Safety First, still has its roots deep in the human race.

Additional footnotes (denoted by ) have been added to provide additional information where suitable.

Chapter One

Ambitions and Dreams

In the geography class at school we knew on paper, three kinds of mountain ranges. There was the mountain range represented by a long line supported on either side by little legs, which straggled pathetically across the page of our freehand geography drawing books, like some starved medival dragon. This method of mountain delineation is technically known as hachuring, but our Geography Master generally referred to mountain ranges drawn thus contemptuously as centipedes and awarded but a low mark to home-made maps drawn in, as he rightly considered, such a slovenly fashion. Then there was the shading method. The idea of this was in imagining the sun to be shining on one side only of the range, the other side being in funereal shadow. Well done it is quite effective, and as there are few schoolboys who can resist rubbing a pencil lead up and down a piece of paper, it was universally popular. Yet, if giving some vague impression of form and relief, the mountain ranges we drew were grim sad affairs as desolate and unattractive as the airless vistas of the moon. And lastly, there was the contour method. This was popular among few owing to the time and labour involved, for unless approximate accuracy was achieved, a map drawn thus was sure to incur the teachers wrath.

Personally, I found much satisfaction in laboriously drawing out and colouring any mountain range portion of the map, sometimes to the exclusion of all else on the map and other items of homework. Geography, was indeed, one of the few subjects in which I took any interest whatever at school, and had it been the only subject necessary to qualify for promotion I might have reached the Sixth. As it was, I was relegated for the remainder of my natural school life to the Fifth Modern, a polite term for Remove, the pupils of which were taught handicrafts on the apparent assumption that their mental equipment was such as to render it impossible for them to make their living otherwise than with their hands.

The green lowlands of the map had little fascination for me. Mentally, I was ever seeking escape from the plains of commerce into those regions, which by virtue of their height, their inaccessibility and their distance from the centres of civilisation were marked, Barren Regions Incapable of Commercial Development. My gods were Scott, Shackleton and Edward Whymper.

There was one portion of the Earths surface at which I would gaze more often than at any other, the indeterminate masses of reds and browns in the map which sprawl over Central Asia. For hours I would pore over the names of ranges, deserts and cities until they were at my fingertips. By comparison with distances I knew the distance to the seaside, or to London I tried to gain some idea of a mountain range the length of which is measured in thousands of miles, the Himalayas.

In imagination I would start from the green plains, and, follow the straggling line of a river up through the light browns of the map to the dark browns, to halt finally on one of the white bits that represented the snowy summits of the highest peaks. There I would stop and dream, trying to picture great mountain ranges lifting far above the world: the dull walls of the schoolroom would recede, and vanish, great peaks of dazzling white surrounded me, the airs of heaven caressed me, the blizzards lashed me. And so I would dream until the harsh voice of the Geography Master broke in with its threats and promises of punishment for slackness and gross inattention. If he had known, perhaps he would have left me there on my dream summits, for he was an understanding soul.

If I had learnt, as much about other branches of geography as I knew about mountains I should, indeed, have been a paragon. As it was, the knowledge gained from every book on the subject on which I could lay my hands had its drawbacks, and I have a distinct recollection of being sent to the bottom of the form for daring to argue that the Dom and not Mont Blanc was the highest mountain entirely in Switzerland.

Three Himalayan names stood out before everything else, Mount Everest, Mount Godwin Austin (now called K2) and Kangchenjunga. Once the knowledge that Everest was 29,002 feet high, instead of a mere 29,000 feet, resulted in my promotion to the top of the form, where for a short time I remained, basking in the sun of the Geography Masters approval (for he was a discriminating man) before sinking steadily to my own level, which was seldom far from the bottom.

For years my ambitions were centred about the hills and crags of Britain; the Alps followed naturally. They were satisfying, if not supremely satisfying, for they enabled me to erect a more solid castle of imagination upon the foundations of my early dreams. On their peaks I learnt the art and craft of mountaineering, and the brotherhood of the hillside. To some the British hills are an end in themselves, and to others the Alps, but the Journeys End of the mountaineer is the summit of Everest.

Is mountaineering worthwhile? many ask. Not to them, but to others. Adventure has its roots deep in the heart of man. Had man not been imbued with it from the beginning of his existence, he could not have survived, for he could never have subdued his environment, and were that spirit ever to die out, the human race would retrogress. By adventure I do not necessarily mean the taking of physical risks. Every new thought, or new invention of the mind is adventure. But the highest form of adventure is the blending of the mental with the physical. It may be a mental adventure to sit in a chair and think out some new invention, but the perfect adventure is that in which the measure of achievement is so great that life itself must be risked. A life so risked is not risked uselessly, and sacrifice is not to be measured in terms of lucre.