Table of Contents

Guide

COPYRIGHT SUSANNA PFISTERER 2016

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying of the material, a licence must be obtained from Access Copyright before proceeding.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Pfisterer, Susanna, 1962, author

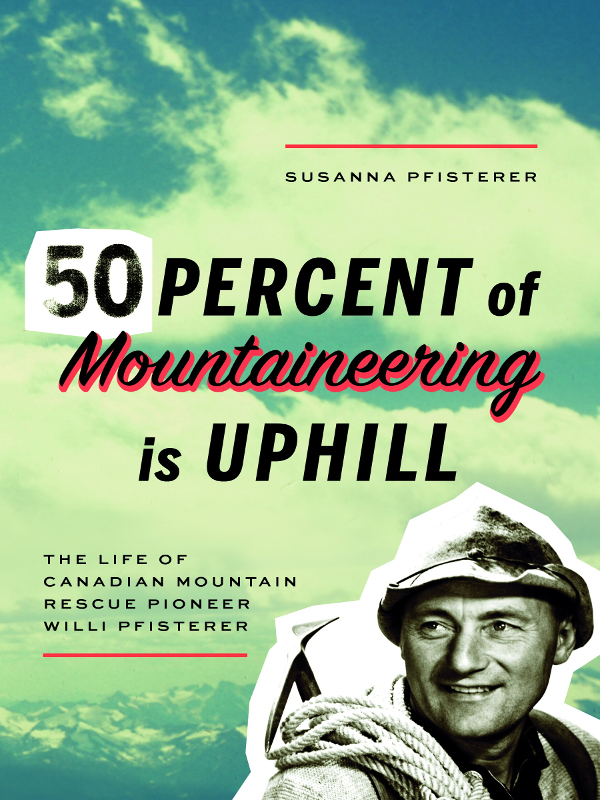

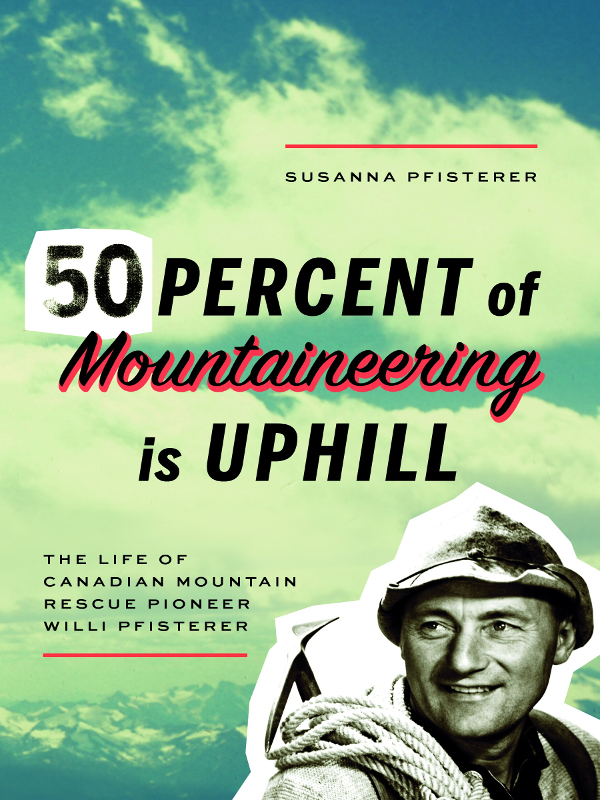

Fifty percent of mountaineering is uphill : the life of Canadian mountain rescue pioneer Willi Pfisterer / Susanna Pfisterer.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-926455-60-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-926455-61-7 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-926455-62-4 (mobi)

. Pfisterer, Willi.. Mountaineers Canada Biography. I . Title.

GV 199.92.P45P45 2016 796.522092 C 2015-906556-9 C 2015-906557-7

Editor: Anne Nothof

Book design: Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design

Author photo: Gerry Israelson

NeWest Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, and the Edmonton Arts Council for support of our publishing program. This project is funded in part by the Government of Canada.

| # 201, 8540 109 Street |

| Edmonton, Alberta T 6 G E 6 |

| 780.432.9427 |

| www.newestpress.com |

No bison were harmed in the making of this book.

Printed and bound in Canada

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15

To Anni and Fred.

SIDEHILLGOUGER : a North American folkloric creature adapted to living on hillsides by having legs on one side of its body shorter than the legs on the opposite side.

CONTENTS

Mount Hochkonig overlooking Muhlbach.

THE SIDEHILLGOUGER SAYS,

Climbing a mountain is simple. Just put one foot in front of the other and repeat.

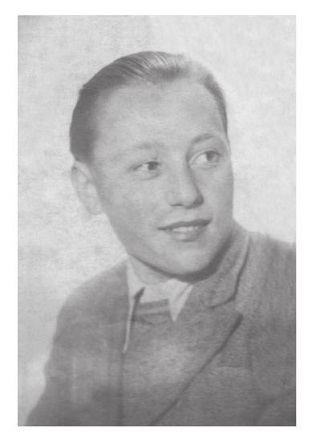

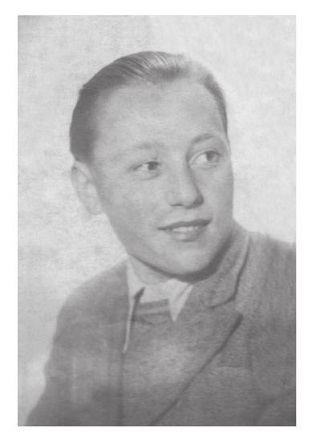

MY MOUNTAINEERING CAREER began with an accident when I was ten years old.

Our family home in those days stood at the upper edge of a small mountain village named Muhlbach, in the Austrian Alps. The house was built on a hillside; a typical alpine-style wood structure, three stories high with a steep pitched roof and every window clustered with flowers. There was a tray of flowers at the bottom, another halfway up, and some pots hanging out to the side of each window. Those colourful blossoms were the pride and joy of my grandmother.

Like many of the other houses in the village, the outside of our home was covered with forester shingles. Each of these shingles measured ten centimetres in width, twenty centimetres in length, and were rounded at the bottom. It literally took thousands of the damn things to cover a wall. My grandfather, a seasoned mountain guide, manufactured and sold them when he was not out climbing, and I, over and above my normal chores, had to carefully pile all that he produced along one wall of the house for them to dry. This was a most tedious and frustrating job for a busy, impatient ten-year-old boy.

The gravel road that wound its way up the valley ended in front of our house. From there, footpaths and a wagon road led further up to the alpine huts and mountains above. Mountaineers from all over Europe would travel to our area to attempt the great climbs accessed from there, sometimes hiring my grandfather to guide them. Often they would ask to store their bicycles or motorcycles in our woodshed.

Many of the famous climbers of the time passed through my domain, and I knew them all. There was Ertl, Frauenberger, Aschenbrenner, Dulfer, Hinterstoiser and Kurz, the Schmidt Brothers, Hechmair and many others. Some of them are still there now, in the little graveyard behind the church. I would watch and listen to these men in awe, always impressed by what a friendly, happy lot they were. While they climbed, I guarded their belongings with my life.

One day, one of these fellows gave me a piton. I couldnt believe my luck a genuine, slightly used, rusty rock piton. In my mind, pitons were synonymous with rappelling, so with gift in hand, I rushed immediately to the work shed to get a hammer and an old piece of rope. Then I climbed up on the house roof and drove the piton into the chimney. I tied one end of the rope to the piton and the other I threw over the edge of the roof. The bottom end of it was at least four metres from the ground, but that didnt slow my enthusiasm. I placed the rope between my legs, up across my chest and over my shoulder just like Dulfer had shown me. Feet apart, I leaned back ready to begin my descent when the piton came out! Down I went, rapidly gaining speed as I schussed down the shingled roof, flat on my back and head first. Remember, the house was three stories high. There was a set of telephone wires at the second-floor level with which I made my first contact. The wires tossed me against the wall of the house. Down the wall I went straight into Grandmothers flowers. I tried to grab hold of the centre tray of flowers as my legs hit and broke the bottom tray, but the brackets holding both came out of the wall and I continued on down.

Flowers, trays, dirt, brackets and I, with the rope still wrapped around me, were all falling as one and then the real disaster happened! I landed on Grandfathers shingles and the entire pile fell over. It took me weeks to straighten those damn things out.

What I considered the biggest stroke of luck though, was that when I was on the ground, flat out among the flowers and shingles and dirt, one of the flowerpots, in delayed action, fell out of its hanger and hit me on the head, knocking me unconscious. This prevented me from getting the biggest spanking of my life.

Thinking of it now, I have that flowerpot to thank for me spending my life in the business of mountaineering.

Injuries aside, that experience left me eager to climb my first real mountain. Every chance I had, I pestered my grandfather to take me climbing with him. The following summer, I saw my opportunity. My Aunt Liesl came from Salzburg with some of her friends for a visit. While there, they wanted to climb Hochkonig, the 2,941-metre peak directly behind our house, with Grandfather.

At the time, like most of the kids in our village, I had only one pair of large-sized boots, which were meant to last me for years. I would begin wearing the boots in the fall when the snow fell and would store them away in the spring when most of the snow had melted. Throughout the summer, I went barefoot.

Our family home minus the flowers.

Aunt Liesl didnt have any boots appropriate for climbing, and without thinking to consult me she asked Grandfather if she could use mine. He agreed. They knew I wanted to climb the mountain and wouldnt want to lend her my boots, so in order to get me out of their hair they sent me on an errand just before they left for their climb.