FATAL MOUNTAINEER: THE HIGH-ALTITUDE LIFE AND DEATH OF WILLI UNSOELD, AMERICAN HIMALAYAN LEGEND. Copyright 2002 by Robert Roper. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Roper, Robert.

Fatal Mountaineer : the high-altitude life and death of Willi Unsoeld, American Himalayan legend / Robert Roper.1st ed.

p. cm.

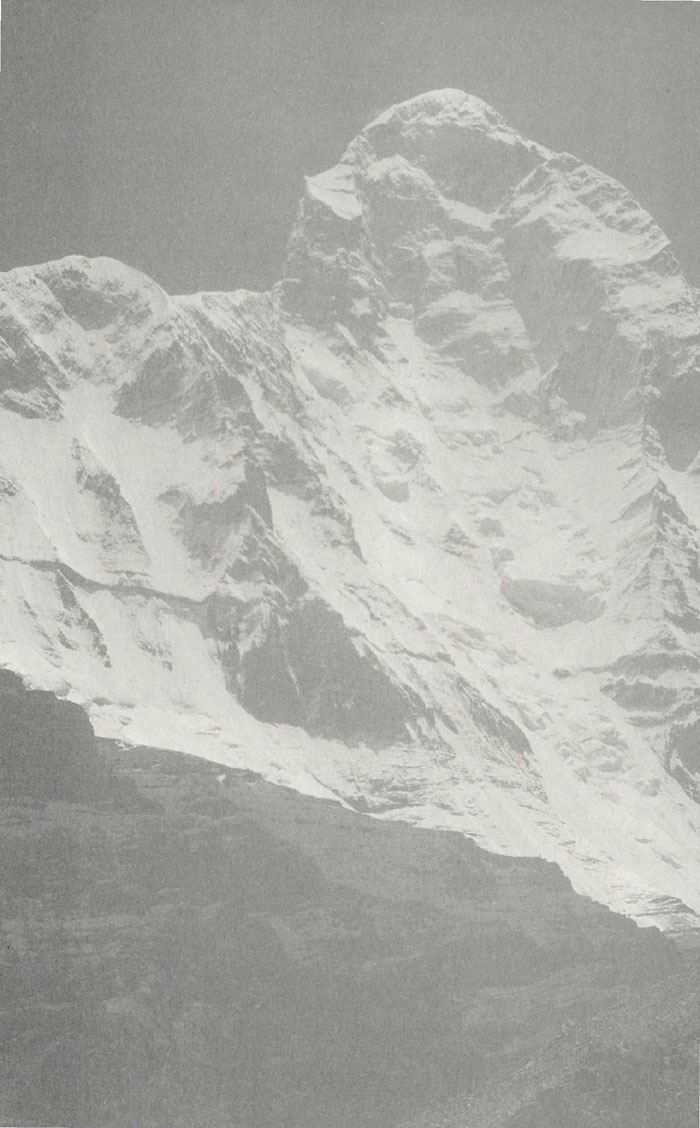

1. Unsoeld, William Francis, 1926-1979. 2. Unsoeld, William Francis, 1926Friends and associates. 3. MountaineersUnited States Biography. 4. MountaineeringIndiaNanda Devi. 5. Nanda Devi (India)Description and travel. I. Title.

Praise for Fatal Mountaineer

A magnificent story a drama worthy of Sophocles Roper is interested in the big questionsfate, the ethics of risktaking, the flaws in character that lead inexorably to tragedyit is strong medicine, and it makes for a strong book.

Anthony Brandt, National Geographic Adventure

A story that has all the riveting qualities of a novel and the added punch of truth outdoor literature at its best . Like the great flawed heroes of classic literature, Unsoeld's story ranges from awe-inspiring to tragic, producing strong contradictory feelings in the reader. It's a rich tapestry, a book for both the general reader and the climbing fanatic.

Floyd Skloot, San Francisco Chronicle

Engaging a provocative look at the legendary climber who himself died in an avalanche in 1979.

Denver Post

[Fatal Mountaineer] is a cautionary tale of how pursuit of a mountain at any cost and in any weather can have deadly consequences. Unsoeld's philosophythat life begins at ten thousand feet and abovemust be challenged.

Lynn Arave, Deseret News

Riveting you care intensely about what happens to the characters as they struggle for the summit of Nanda Devi . Roper paints a complicated picture of Unsoeld, warts and all. The beloved teacher's passion for mountaineering and the outdoors inspired many, but his thirst for high-altitude risk cost him.

Prentiss Findlay, Charleston Post & Courier

Gripping a provocative look at a still-legendary climber.

Publishers Weekly

Roper tells a story packed with adventure, suffering, scandal, heroism, and controversy fascinating.

Kirkus Reviews

I longed for the intellectual rigor of Robert Roper's marvelous Fatal Mountaineer, which I was reading concurrently with [another book under review] I had to give myself ten-minute treat breaks [of it].

Carolyn See, Washington Post

Like Anthony Bourdain's Kitchen Confidential, Robert Roper's Fatal Mountaineer is like a juicy absorbing magazine article that just keeps going and you want to stay with it for hundreds of pages fascinating.

Our Town

ALSO BY ROBERT ROPER

Cuervo Tales

The Trespassers

In Caverns of Blue Ice

Mexico Days

On Spider Creek

Royo County

Big Bets Gone Bad (coauthor with Phillipe Jorion)

INTRODUCTION

On March 4, 1979, a man descending Washington's Mount Rainier was swept away in an avalanche. A young woman, coming behind him on a rope, also was carried down a steep slope beneath a pass called Cadaver Gap.

It was snowing hard. Visibility was low, and strong winds scoured the incline. In the last twenty-four hours three feet of new snow had accumulated on the mountain's southern side. The barometer reading was quite low. The weather did not look like improving.

In an avalanche, snow, no matter how powdery, turns into a substance that resembles wet cement. And as soon as movement ceases, it sets up hard. Thus the standard advice on how to behave in an avalancheto swim with it, make a breathing space around your headoften comes to nothing. Everything happens with appalling force and someone buried just under the surface may be fatally entombed.

As it happened, the man descending first on the rope that day, a fifty-two-year-old college professor named Willi Unsoeld, was buried not too far under, but far enough so that his arms and legs were immobilized. His throat and nostrils filled with snow, and the pack on his back pinned him down. The slide that carried him and Janie Diepenbrock, the young woman, away did not crush their bones, but neither did it let them move. It simply held them and then it was all over.

Unsoeld was leading twenty-one people off the mountain, students of his at Evergreen, a state college in Washington. They had experienced Mount Rainier in some of its more elemental moods, huddling in snow caves for two nights and waiting out storms in nylon tents, which burst their seams from accumulated snow. After seven days it could be said that the group had shown a lot of spunk just getting up as high as it had, with some members climbing within fifteen hundred feet of the 14,411-foot summit. Most of them had had a good time. They were enrolled in an outdoor-education program at Evergreen, thus were self-selected for grit and adventure-hunger.

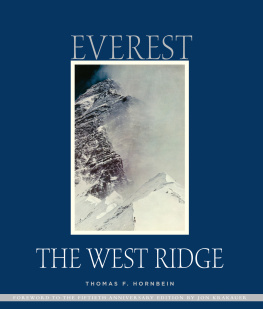

To climb Rainier in winter is always the real deal, but Willi Unsoeld was famous as a purveyor of the genuine article in the outdoors. Throw in no line, catch no fish was his philosophy, and his own life was a testament to the transfiguring influence of mortal risk. Fifteen years before, he had been America's strongest Himalayan climber. He would always be remembered for the 1963 first ascent of Everest's West Ridge, with Tom Hornbein, one of the most audacious high-altitude climbs in history. Usually the strongest, most forward-thinking member of any group going for a great summit, Unsoeld was also a plain wonderful guy, terrific company in a tent during a five-day blow. He was that modern rarity, a philosophy professor who had a philosophy. He was thoughtful and intuitive about other people. Among mountaineers he was legendary, and within his enormous circle of acquaintance deeply beloved.

At age fifty-two, with both hips recently replaced by orthopedic surgery, most of his toes missing due to frostbite suffered on that Everest climb, he was hardly a world-class specimen anymore. Still, you could do worse than to find yourself in a blizzard with Willi Unsoeld. He had climbed Rainier some two hundred times. After years as a professional guide there and in the Tetons, his mountain sense was highly developed, to say the least. At Cadaver Gap Unsoeld made a typically ballsy, yet calculated, move: with members of his party exhausted and borderline hypothermic, he chose the route of descent that, while marginally more dangerous, promised to bring them to safety quickest. (They were within a few hundred yards of a mountain hut.) He led off in the howling stinging whiteness, with Diepenbrock and two others behind him on a rope; but a snow slab, three feet thick and hundreds of yards square, sheared off under them and rudely decided the outcome of the day.