| That anyone should want to climb a high mountain solely for pleasure, is, at the present time, simply not understood by these mountain peasants. The exceptions are a few Sherpas who have developed a feeling for the beauty of the mountains and have discovered the pleasure of conquering peaks, owing to repeated participation in expeditions. This is especially true in the case of my own Sherpa, Aila, who was my companion for seven years. Often when we were sitting on a summit with a magnificent panorama spread out before us, he would say very dryly, Very much country, sir. This was his way of expressing his pleasure at the wonderful view. Latterly he went so far as to say, Very beautiful country, sir. There was a wealth of enthusiasm behind these terse remarks. |

TONI HAGEN

EVEREST

The West Ridge

THOMAS F. HORNBEIN

FOREWORD BY JON KRAKAUER

| A LEGENDS AND LORE TITLE THE MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS |

Until one is committed there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sor ts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in ones favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way. I have learned a deep respect for one of Goethes couplets:

Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.

W.H. MURRAY

CONTENTS

To friends and family who have shared my passionate affair with high places and thin air.

You know who you are.

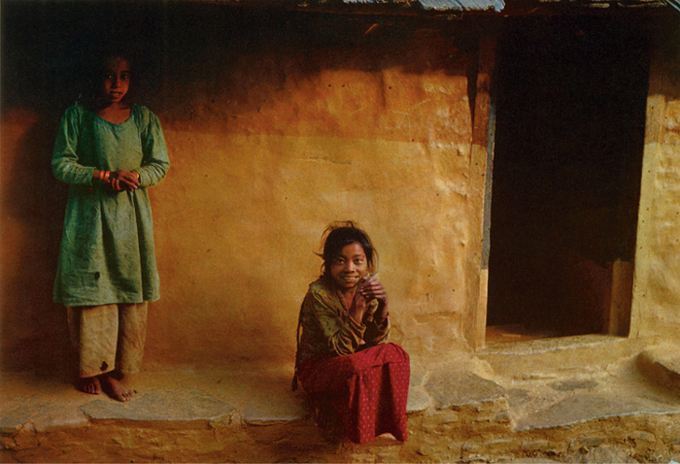

Girl in doorway, Kathmandu (Photo by James Lester)

A temple and prayer flags in Bodnath (Photo by Tom Hornbein)

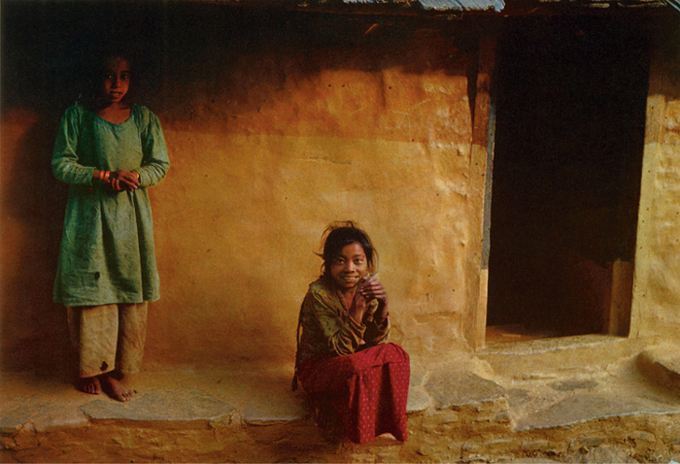

Sisters in Those (Photo by James Lester)

FOREWORD

by Jon Krakauer

M ost present-day climbers who attempt Everest start trekking to the mountain after flying to a Nepalese village called Lukla. Perched 9,500 feet above sea level, boasting an airport that handles fifty or more flights a day during prime trekking season, Lukla is situated just thirty miles from Everest Base Camp. In 1963, however, when the American Mount Everest Expedition (AMEE) embarked for the Himalaya, there was no airport in Lukla, or even a dirt landing strip, and the nearest road ended a few miles outside of Kathmandu. For the AMEE, getting to the base of Everest entailed 200 miles of hard walking.

On the third evening of their month-long trek, the climbing team assembled to discuss the expeditions goals. Their primary objective had always been to make the first American ascent of Everest, by way of the South Colthe route pioneered by Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary a decade previously. Prior to 1963, six men had climbed the worlds highest mountain via the South Col, and three others had reached the summit by the Northeast Ridge, on the Tibetan side of the massif. To a small cohort of the AMEE climbers, the prospect of reascending the South Col route seemed like small beer. Willi Unsoeld, Tom Hornbein, Barry Corbet, Dick Emerson, Jake Breitenbach, and a couple of others were much more interested in attempting an entirely new route via the formidable West Ridgean idea first floated by expedition leader Norman Dyhrenfurth several months earlier.

As the discussion got underway, Hornbein raised his compadres eyebrows by proposing that they scrap their plans for the South Col route, which offered a much greater chance of success, and instead direct the full brunt of the expeditions resources at the West Ridge, even if it meant failing to put anyone on the summit. Although Dyhrenfurth quickly shot down Hornbeins suggestion, the team agreed to try the West Ridge as a secondary objective, after the summit had been reached by the South Col. Following the meeting, Dyhrenfurth noted in his diary that if they could somehow pull it off, the West Ridge, would be the biggest possible thing still to be accomplished in Himalayan mountaineering. During another powwow a week later, however, he cautioned, Lets not go overboard on the West Ridge. I am just as excited about the West Ridge as you are. But lets not jeopardize the South Col. Lets not make the mistake of throwing all the power, all the oxygen, into the West Ridge, because the Col is still our guarantee of success.

For the next two months, almost all of the teams efforts were focused on putting an American on the summit by way of the South Col. At 5:10 PM on May 2, Hornbein and Unsoeld were taking a rest at Base Camp when the radio crackled to life. The Big One and the Small One made the top! announced the excited voice of Gil Roberts, calling down from a camp 4,000 feet higher on the mountain. Despite fierce winds that had blasted the upper peak, Jim Whittaker and Nawang Gombu Sherpa had reached the summit from the South Col the previous day. Hornbein and Unsoeld spontaneously threw their arms around one another in an emotional embrace, overcome with joy for Big Jim and Gombu. But Tom and Willi had another reason to be thrilled, as well: Their friends success had just granted Tom, Willi, and the rest of the West Ridge crew the opportunity to pursue their pipe dream.