The author wishes to thank Anders Bolinder and Ulrich Link for early work on the Everest Chronicle; Xavier Eguskitsa, Elizabeth Hawley and Eberhard Jurgalski for recent facts in listings in editions of Peter Gillmans Everest book and the American Alpine Journal, the Himalayan Journal and other sources.

Photos used in the book: Leo Dickinson, M. Rnnau, Robert Schauer, J. Ullal. Other photos are from the archives of the author or publisher. G. Lange for his map illustration, W. Quitta for his sketches and other illustrations.

Everest 2000

Mount Everest continues to make negative headlines: as a rubbish tip, a fatal magnet for adrenaline-freaks, or as an amusement park for tourists who have been everywhere else. Ever since word got out that you could purchase the climb of your dreams, an ascent of the highest mountain of the world revered as holy by those living to the south or north of 'Sagarmatha or Qomolungma (its local names), it became transformed into a consumer product. In Kathmandu and Lhasa, government departments and service-providers benefit from an Everest boom built upon the mythology which, over almost eighty years, has grown around a couple of dozen expeditionary mountaineers from Mallory to Ang Rita.

Mount Everest tends to shrink in our imagination when we read it has been conquered by a couple of hundred mediocre alpinists, who probably would not trust themselves to climb Mont Blanc without help; but then it grows again, if a half dozen of these trophy-hunters get themselves killed in the process, as happened in 1996 in the course of two commercial climbing trips organised by Rob Hall and Scott Fischer. Jon Krakauer has written a profound book upon the subject, Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mount Everest Disaster. Despite this, the hordes came again the following year, and once more there were tragedies.

We seem to have lost sight of the fact that humans cannot survive at heights approaching 9,000 metres. While more and more of us climb where we dont belong, the accidents will go on increasing and, with them, because of them in fact, so will the desire to make such an attempt. Treading the footsteps of those before them, waiting in line at the Hillary Step below the summit, growing numbers of people clamber to heights that offer no retreat for the inexperienced when storm, mist or avalanche play havoc with fuddled brains. What makes Mount Everest so dangerous is not the steepness of its flanks, nor the vast masses of rock and ice that can break away without warning. The most dangerous part of climbing Mount Everest is the reduced partial pressure of oxygen in the summit region, which dulls judgment, appreciation, and indeed ones ability to feel anything at all.

With modern, lightweight oxygen apparatus the mountain can be outwitted, but what happens when the bottles are empty, when descent through a storm becomes impossible, when you cant go a step further? An Everest climb cannot be planned like a journey from Zurich to Berlin, and it doesnt end on the summit. In any sports shop you can buy, for a price, the lightest equipment there is, but you cannot purchase survival strategy. The client surrenders responsibility for him- or herself to the guide and the higher the mountain, the more personal responsibility is yielded up, even though this is the basic prerequisite for any mountain experience. And what happens when the leader gets into difficulty? Clients are left hanging in the ropes on a mountain they neither know nor understand.

This Everest is no longer the Everest of the pioneers. Increasingly the apex of vanity, it has also become a substitute for something the summit-traveller wants to flaunt on his lapel, like a badge, without taking any of the responsibility in the field.

The more Mount Everest is turned into a consumer article, the more importance attaches to the key moments of its climbing history with or without supplemental oxygen. As the highest mountain in the world for trekkers, climbers, environmentalists, and aid workers (to say nothing of undertakers) it is guaranteed more publicity than other mountain. Its mythos is continually being misinterpreted, so that it becomes a mountain of fortune and fantasy even for those with no need to go there themselves. For them, I tell this story of climbing by fair means.

Everest as Consumable

Since the beginning of the 1990s more than a thousand people a year converge on the flanks of the worlds highest mountain: hundreds on the north side (Tibet), a few on the east side (Tibet), with the bulk continuing to approach from the south (Nepal). Although permits have become more expensive and parties are threatened with all sorts of restrictions, Mount Everest has degenerated into a fashionable mountain. Dozens make it to the summit each year. The increase in numbers attempting the climb produces a correspondingly higher number of successes and, on top of that, with so many expeditions on the mountain simultaneously, the actual climbing has become far easier: the ice fall is protected with fixed ropes and ladders, the trail broken and marked, high camps established, so that the line of the route is obvious for most of the way to the summit. Todays Everest climber is scarcely ever exposed or completely alone; he or she climbs in a crocodile formation. And any exceptions to this scenario are increasingly rare.

For the first time, in the spring of 1979, a Yugoslav expedition successfully climbed the very difficult West Ridge: over the Lho La, the West Shoulder, and directly up the rocky ridge to the summit.

In February 1980, two days after the winter climbing season ended officially, Polish mountaineers became the first to climb to the top of the world at the coldest time of year.

Russian mountaineers claimed the South Pillar in pre-monsoon 1982. Technically, this prominent rock buttress to the left of the South-west Face may well be the most difficult route on the mountain.

In 1983 a team of distinguished American mountaineers at last succeeded in finding a route up Everests East Face, known as the Kangshung Face.

The Great Couloir on the North Flank, between the North Ridge and a blunt pillar in the central section of the massive face, was climbed by an Australian team in 1984. Variations to the line were done later.

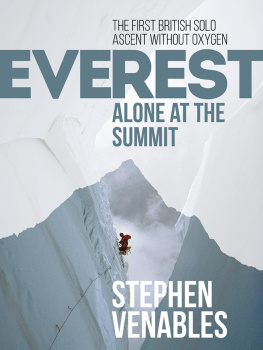

In 1988, ten years after the first ascent of the mountain without oxygen masks, Stephen Venables made it to the top of Everest after an incomparable achievement. Forming a small, unsupported expedition with Robert Anderson and Ed Webster, Venables struggled up a new line to the left of the American Route on the Kangshung Face. All three reached the South Col without supplemental oxygen, climbed higher and survived the panic of losing themselves at those forsaken heights. Venables reached the summit alone and, days later, despite frostbite and complete exhaustion, the crazy trio returned safely to base camp.