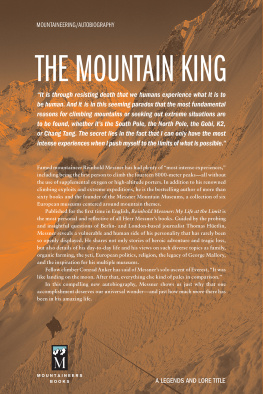

In 2004 and then again in 2014, legendary climber Reinhold Messner sat down with journalist Thomas Hetlin for a series of wide-ranging conversations. In the resulting exchange, Messner reflects on how his life experiences led him from his childhood in postwar Italy to becoming the worlds most renowned mountaineer to his current passion: curating a group of six museums about mountains, collectively known as the Messner Mountain Museums.

CHAPTER I

DEFYING GRAVITY

19491969

Thoughts worth thinking should not just be understood; they should be experienced.

Count Harry Kessler,

May 1896

A CHILDHOOD ON THE ROCKS

I have been a rock climber for as long as I can remember.

As a boy, I didnt just climb on the cliffs of the local Geisler peaks; I climbed on the house-sized boulders at the edge of the forest, on the walls of ruined buildings, and on the cemetery wall during school break time. Most of all, I dreamed of climbing.

Thinking I was a little more able than I actually was, I imagined myself climbing steeper and steeper rock facesuntil it seemed that no route was impossible for me. In my minds eye I managed to make a series of first ascents on the highest faces in the Dolomites, and on the Eiger, Kilimanjaro, and Aconcagua.

I was also attending school and, like all my brothers and my sister, I had to help look after the chickens at home; it was these that made it possible for my parents to feed nine children. My father was a village schoolteacher. He was also my first climbing mentor, but by the age of ten or twelve I was climbing harder routes with my younger brother, and we were soon to enter a realm that belonged to us alone.

During my last few years of school, I came to realize that my path to knowledge would not lead me to libraries, professors, universities, and studies. My path to knowledge was through living life and experiencing reality. I could learn plenty secondhand, but nothing was ever to surpass the experiences I had in the wilderness. All my knowledge of social, scientific, and religious issues has been acquired through personal experience.

This is one of the reasons why in later life I kept forcing myself to organize the next expedition, the next big trip. How often on an expedition have I told myself, Thats enough! and then a few weeks later when the effort, worry, and hardship were forgotten, I began dreaming about a new journey, planning a new climb. Pretty soon Id be off again. And once again, it would be dangerous.

I never intended to risk my neck, but I knew that if I were ever to stop dreaming or traveling I would be old. And that would drive me to despair.

It was midday, and the four of us were sitting on a sharp, rocky ridge on the Secda in the Geisler Rangemy father, two of my brothers, and me. Above us was the Kleine Fermeda. The south face was bright in the sun. It looked steep but well featured; the line of the route was logical. A few scattered clouds hung like cotton wool over the peaks of the southeastern Dolomites, which rose above the Puez Plateau. That meant the weather was going to stay fine.

It wasnt curiosity or high spirits alone that made me keep looking up at the face above us; it was more than that. Perhaps it could be described as the desire to measure up.

Since my father had no objections, I set off alone without a rope. I scrambled down a rocky terrace for a bit, then climbed up and rightward. The rock was quite smooth, and it wasnt particularly steep at the start, although the cliff dropped away abruptly beneath me. I didnt look down, only at the rock face in front of me, taking it step-by-step, hold-by-hold. This was exactly what I wanted to do, to climb without distractions, following my instincts, finding the route as I went. I felt proud of myself.

I had now arrived at the crux and took a good look at the vertical wall above me. After spying out a series of handholds and footholds, I started climbing again.

Everything else was forgotten; it was just handholds and footholds and unrestrained movement. I was oblivious to everything around me. I might have hesitated briefly, looked down at my feet and seen the abyss that dropped 300 meters to the green alpine pastures below. After a few meters the climbing got easier again, and I was soon standing, carefully, on the south summit before scrambling up loose rock to the main summit. Looking north, I could see right down to the pastures of the Gschmagenhart Alm, where we had set out from that morning. To the south I could see all the famous Dolomite peaks, from the Langkofel to Sass Songher, with the Marmolada, Monte Pelmo, and the Civetta behind.

Climbing for me was more than a sport. Danger and difficulty were part of the game, together with adventure and exposure. Climbing a big route means total commitment. It requires total reliance on yourself for maybe several days as you try to unlock its secrets.

Climbing is all about freedom, the freedom to go beyond all the rules and take a chance, to experience something new, to gain insight into human nature. And there is always more than one answer to a question, more than one story behind every experience. For me, imagination is more important in climbing than muscle or daredevil antics. It is worth more than technology. The development of the person is more important than having bolt ladders everywhere. There are few treasures to be found in bolt-protected climbs. We need to protect the diversity of climbing, not every meter of rock.

H: You grew up in Villnss, a valley in South Tyrol at the foot of the Geisler Range that has remained pretty much unspoiled to this day. Who was at the top of the hierarchy of this unspoiled cosmosGod?

M: No, the most powerful person in the valley was the man with the biggest farm. Then there was the parish priest, a venerable old gentleman who we all respected. My father was the senior teacher and headmaster of the school in the valley.

H: Your father also bred rabbits. Why was this?

M: We were nine children, and my father needed the extra income. My mother used to shear the rabbits and sell the angora wool. We butchered a few as well, but we kept the fifty or sixty rabbits mainly for their wool, angora woolvery valuable wool.

H: And you also had a chicken farm.

M: We ended up with thousands of chickens. We supplied chicks and pullets all over South Tyrol. All of us children had to lend a hand. I started working in the henhouse at the age of six.

H: How many hours did you have to work?

M: In the summer six, seven, eight hours.

H: A day?

M: