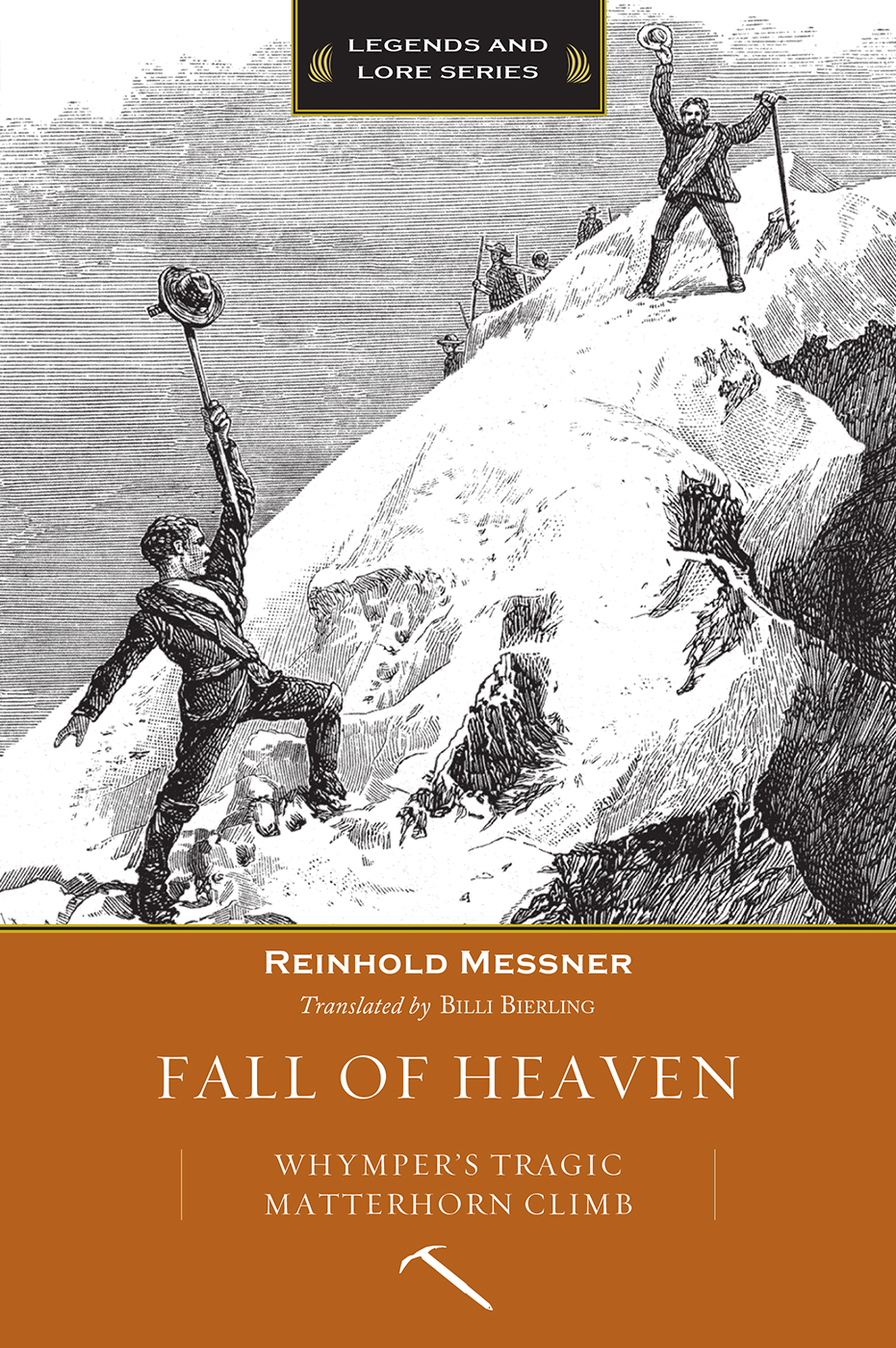

FALL OF HEAVEN

WHYMPERS TRAGIC

MATTERHORN CLIMB

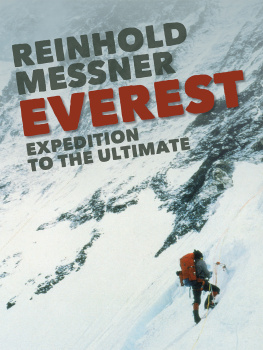

REINHOLD MESSNER

TRANSLATED BY BILLI BIERLING

LEGENDS AND LORE SERIES

Mountaineers Books is the publishing division of The Mountaineers, an organization founded in 1906 and dedicated to the exploration, preservation, and enjoyment of outdoor and wilderness areas.

1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201, Seattle, WA 98134

800.553.4453, www.mountaineersbooks.org

Copyright 2015 by Reinhold Messner

Translation 2017 by Billi Bierling

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Originally published as Absturz des Himmels

(c) S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

20 19 18 171 2 3 4 5

Copyeditor: Chris Dodge

Series design: Karen Schober

Layout: Jen Grable, Mountaineers Books

Cover and interior illustrations from Scrambles Amongst the Alps by Edward Whymper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available on file.

Mountaineers Books titles may be purchased for corporate, educational, or other promotional sales, and our authors are available for a wide range of events. For information on special discounts or booking an author, contact our customer service at 800-553-4453 or .

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-68051-085-0

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-68051-086-7

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

NO OTHER MOUNTAIN IN THE world has such distinct features as the Matterhorn. It appears inaccessible from all sides. What did the residents of the Swiss canton of Valais think or feel thousands of years ago, when they first set eyes on the mountain that locals to this day call Horu? Did they worry that avalanches or rocks would tumble down onto their pastures and destroy their livelihoods? Could they predict the weather in the mists gathering on its flanks? Or were they just too frightened to go anywhere near it?

The initial name given to this unique mountain is said to have been Mons Silvius. The Swiss philosopher and geologist Horace-Bndict de Saussure, as well as the Schlagintweit brothers, who published a geological geography of the Alps in 1854, used the name Mont Cervin in their reports, and both noted 1682 as the first record of the names Zermatt and Matterhorn.

When Saussure first passed through the Valtournenche Valley on his way to the southern base of the Matterhorn in 1789, he had no intention of climbing this awkward-looking mountain. Two years previously he had stood atop the highest mountain of the Alps, Mont Blanc. There he took barometer readings to establish the exact height of the peak.

In 1789 there was no route to the top of the Matterhorn, which rises gigantically into the sky over the wide pastures of Breuil. The triangular obelisk, looking as if it had been chiseled, was considered unscalable. Its ragged cliffs, too steep to allow snow to cling, would not allow even the thought of an ascent.

On his second trip to the Alps in 1792, Saussure started in Valtournenche, advanced to the Col de Saint-Thodule, and stayed there for three days to analyze the structure of the Matterhorn and determine its exact height. He collected rocks, plants, and insects, wondering how the glacier fleas could possibly live in such cold temperatures and take such big leaps across the snow. Fifty years later, herdsmen of Breuil would remember the noble stranger who had insinuated himself into their lives, the tall man who excavated the remains of a fort at the col south of the Matterhorn. Saussure believed that the Valdostansthe people living in the Aosta Valleybuilt the Fort de St. Thodule to defend against attacks launched by the Valaisans.

The natural scientist, geologist, and philosopher James David Forbes continued the work of Saussure. He also considered the Matterhorn to be the most different mountain in the Alps. At that time, with alpine exploration in its infancy and mountain climbing considered an exotic pastime for wealthy people, the myth of the Matterhorn was born. The locals could not fathom why strangers, who had all possible comforts at home, came to their poor valley to hike the slopes of inhospitable and dangerous mountains, sleep in hay barns, and scale icy mountaintops when they could instead have traveled by coach through industrial cities and slept in comfortable hotels.

In the summer of 1880, around the time Napoleon and his army crossed the Great St. Bernard Pass to advance into Italy, the English crossed the Col de Saint-Thodule. They arrived in the Valais from Valtournenche, frightening the vicar of St. Niklaus, who had never had the pleasure to meet an Englishman. He hoped that the St. Niklaus Valley and his congregation would be spared the influence of tourism.

It took forty years for the village physician, Dr. Lauber, to open the first inn in the valley, the Du Mont Cervin, which had a kitchen and three guest beds. Now more and more tourists, first and foremost English, flocked to the Alps to visit this gigantic natural amphitheater. The Matterhorn, which was hailed the miracle of miracles, still only attracted the interest of scientists (Forbes was not alone in believing the most wonderful peak in the Alps to be unscalable).

In 1844 the English writer, painter, and philosopher John Ruskin arrived in Zermatt, where from the north he created an image of the Matterhorn that would become well known. His parents, who had taken him on a trip to the Alps when he was fourteen, had kindled his interest in the mountains, and after reading Saussures Voyages dans les Alpes, given to him by his father, Ruskin found his way to nature. Nature has given me a new life, he wrote, which will only find its end at the gates of the mountain of no return. Through William Turners paintings, which show mountains ravaged by thunderstorms or dipped in beautiful sunsets, the romantic philosopher learned to recognize what he called the architecture of mountains.

In 1855 Alexander Seiler, who was not a native, opened a guesthouse with six beds in Zermatt. Two years later, the English set up their exclusive Alpine Club, whose members had to prove that they had climbed higher than 13,000 feet (4,000 meters). The Matterhorn and its twenty-nine surrounding 4,000-meter peaks became their preferred playground. Interest in mountaineering was growing. English sport enthusiasts scaled more and increasingly difficult peaks with their Swiss mountain guides. Only one mountain, the Matterhorn, remained out of the question. The fact that guides believed it unscalable soon became incentive for many alpinists, however, who viewed it as a challenge.

East of the Matterhorn, a nine-year struggle for Monte Rosa ended in 1855, when its highest peakthe Dufourspitzewas conquered on August 1 by a party of eight: Matthus and Johannes Zumtaugwald, Ulrich Lauener, Christopher and James Smyth, Charles Hudson, John Birkbeck, and Edward Stephenson. Other mountains in the Zermatt area were being scaled, and only the enigmatic Matterhorn remained untouched, as if it was taboo. The Matterhorn can be conquered, wrote Alsatian scholar Daniel Dollfus-Ausset that year. A balloon made of extraordinarily durable material and of a certain shape tied to a long rope... would allow an aeronaut to steer his gondola and land on its top.

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper