INTRODUCTION

Peter Gillman

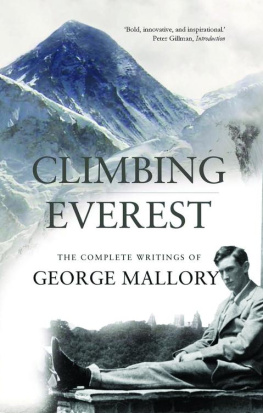

On 12 April 1922, George Mallory sat down to write a letter to his wife Ruth. The British Everest expedition had just reached the Tibetan fortress town of Kampa Dzong, having fought its way through a blizzard which had obliterated their tracks and rendered the Tibetan plateau into a wasteland of snow and ice. As Mallory related, he was wearing two sets of underclothesone wool, the other silka flannel shirt, a sleeved waistcoat, a lambskin jacket and a Burberry coat, as well as plus fours, two pairs of woollen stockings, and a pair of sheepskin boots. Yet his hands were so cold, he told Ruth, that he could hardly manage to grip his pen.

It says a great deal about Mallorys tenacity and dedication that he completed his letter , telling Ruth about the shadows of mountains moving over the plains and the delicate shades of red and yellow and brown of the landscape before the snow came. It also reveals much about Mallorys view of himself as writer. In the first place, he regarded it his duty to posterity that he should faithfully record the sights and events the 1922 expedition encountered on its arduous five-week trek to Everest. In the days when history was still inscribed in pen and ink, letters were seen as vital links in the testimonial chain, and Mallory certainly had a sense of the expeditions part in the developing saga of human exploration.

His writing also met more personal goals. George and Ruth Mallory had married in July 1914, on the very eve of the First World War. As an artillery officer, Mallory spent a year and a half, with intervals, on the western front. Throughout that period he and Ruth had sustained their marriage by writing to each other regularlyin Ruths case, every single day. Thus when Mallory departed for Everest, doing so three times in the space of four years, they continued the practice as a way of keeping their relationship and their love alive.

Both during the war, and while Mallory was away on Everest, their exchanges were always endearingly intimate: Ruth tells George about the latest doingsand misdeedsof their three young children, Clare, Berry and John. She recites her domestic concerns, her encounters with Georges parents and with hers, the state of the garden at their home in Godalming, Surrey. George is almost as gossipy in response, giving his views of his brother officers on the Western Front and his fellow climbers in Tibet, as well as describing the more momentous progress of both the war in the France and the expedition in Tibet. Their letters are all the more poignant given that their love was doomed, destined to end when Mallory disappeared near the summit of Everest a little less than ten years after they were married.

Once back home in Godalming, Malloryto use a very modern phraserecycled his letters to provide his contributions to the official books of the expeditions. Although he removed the less discreet references to his fellow-climbers, the thrust of the narrative, and the quality of his descriptions, are essentially the same. The account which constitutes six chapters of Everest Reconnaissance 1921 shines even more by contrast with the eleven flat, tedious chapters written by Lt Col Charles Howard-Bury, the expedition leader, which Mallory justly described as quite dreadfully bad.

It was in response to this kind of monotonous prose, devoid of all affect, that Mallory had been developing his own theories of writing. It also stemmed from his involvement with the Bloomsbury group and what was termed the Cambridge School of Friendship, where emotional openness and honesty were all. Mallory believed it was vital that mountaineering writing should function on an emotional level, disclosing the participants feelings and attempting to evoke them in the reader. Not for him the stiff upper lip of traditional mountaineering prose, whose authors did their best to conceal their sentiments behind layers of irony and understatement.

Mallory liked to conjure new epithets too: at the tiny settlement of Shilling during the approach march in 1921, he wrote how the wind, a relentless, ever-present force, swept over the sand of a river bank so that it rippled like a sea of watered silk. Such descriptive touches illustrate Mallorys primary delight in savouring new experiences, one of the key motivations of his life, and his determination to render them in a way that others starting with his beloved Ruthcould comprehend.

Mallory had embarked on this process at least a decade before. His published canon is not large: he wrote a total of six articles for the two principal climbing publications of the day: the Alpine Journal, published by the Alpine Club, and the Climbers Club Journal. The first of these, The Mountaineer as Artist, written in 1913, illuminates his theories about both mountaineering literature and writing in general.

Mallorys immediate topic was the meaning of risk in mountaineering. It is significant that he should address this, as mountaineerings practitioners can attempt to delude themselves and family and friendsinto believing that theirs is not an unduly dangerous pursuit , providing only that they obey the safety rules. Equally telling, Mallory wrote his article at a time when the select coterie who comprised the core of British mountaineering were reeling from the deaths on several of their members in climbing accidents in Snowdonia and the Alps.

Geoffrey Winthrop Young, one of the impresarios of the British climbing world, and the principal sponsor of Mallorys career, was among the most distressed at the deaths, observing that they marked the end of climbings age of innocence. Mallory courageously grappled with these issues in the article, scrutinising the validity of the climbers experiences , and producing the metaphor of a symphony to represent the rhythms of climbing s aesthetic and emotional appeal. Although Mallory was uncertain whether his article had succeeded in its aim, it represented a prescient attempt to identify the emotional core of all sporting experiences which prefigures the recent wave of sports writing.