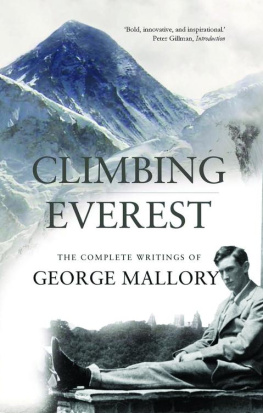

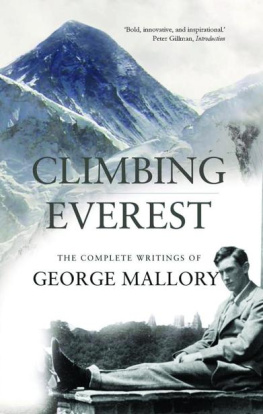

The new base at Kharta established by Colonel Howard-Bury at the end of July was well suited to meet the needs of climbers, and no less agreeable, I believe, to all members of the Expedition. At the moderate elevation of 12,300 feet and in an almost ideal climate, where the air was always warm but never hot or stuffy, where the sun shone brightly but never fiercely, and clouds floated about the hills and brought moisture from the South, but never too much rain, here the body could find a delicious change when tired of the discipline of high-living, and in a place so accessible to traders from Nepal could easily be fed with fresh food. But perhaps after life in the Rongbuk Valley, with hardly a green thing to look at and too much of the endless unfriendly stone-shoots and the ugly waste of glaciers, and even after visions of sublime snow-beauty, a change was more needed for the mind. It was a delight to be again in a land of flowery meadows and trees and crops; to look into the deep green gorge only a mile away where the Arun goes down into Nepal was to be reminded of a rich vegetation and teeming life, a contrast full of pleasure with Nature's niggardliness in arid, wind-swept Tibet; and the forgotten rustle of wind in the willows came back as a soothing sound full of grateful memories, banishing the least thought of disagreeable things.

The Kharta base, besides, was convenient for our reconnaissance. Below us a broad glacier stream joined the Arun above the gorge; it was the first met with since we had left the Rongbuk stream; it came down from the West and therefore, presumably, from Everest. To follow it up was an obvious plan as the next stage in our activities. After four clear days for idleness and reorganisation at Kharta we set forth again on August 2 with this object. The valley of our glacier stream would lead us, we supposed, to the mountain; in two days, perhaps, we should see Chang La ahead of us. A local headman provided by the Jongpen and entrusted with the task of leading us to Chomolungma would show us where it might be necessary to cross the stream and, in case the valley forked, would ensure us against a bad mistake.

The start on this day was not propitious. We had enjoyed the sheltered ease at Kharta; the coolies were dilatory and unwilling; the distribution of loads was muddled; there was much discontent about rations, and our Sirdar was no longer trusted by the men. At a village where we stopped to buy tsampa some 3 miles up the valley I witnessed a curious scene. As the tsampa was sold it had to be measured. The Sirdar on his knees before a large pile of finely ground flour was ladling it into a bag with a disused Quaker Oats tin. Each measure-full was counted by all the coolies standing round in a circle; they were making sure of having their full ration. Nor was this all; they wanted to see as part of their supplies, not only tsampa and rice, but tea, sugar, butter, cooking fat and meat on the Army scale. This was a new demand altogether beyond the bargain made with them. The point, of course, had to be clearly made, that for their so-called luxuries I must be trusted to do my best with the surplus money (100 tankas or thereabouts) remaining over from their allowances after buying the flour and rice. These luxury supplies were always somewhat of a difficulty; the coolies had been very short of such things on the Northern sidewe had no doubt that some of the ration money had found its way into the Sirdar's pockets. It would be possible, we hoped, to prevent this happening again. But even so the matter was not simple. What the coolies wanted was not always to be bought, or at the local price it was too expensive. On this occasion a bountiful supply of chillies solved our difficulty. After too many words, and not all in the best temper, the sight of so many of the red, bright, attractive chillies prevailed; at length my orders were obeyed; the coolies took up their loads and we started off again.

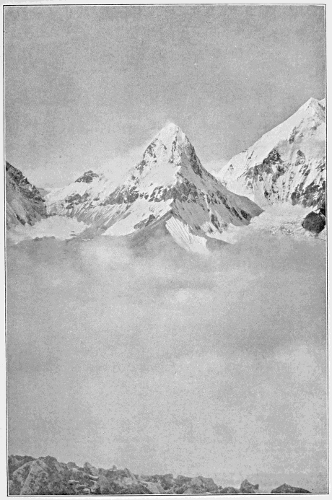

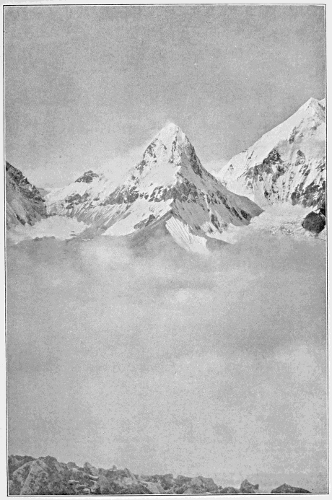

Pethang-tse.

With so much dissatisfaction in the air it was necessary for Bullock and me to drive rather than lead the party. In a valley where there are many individual farms and little villages, the coolies' path is well beset with pitfalls and with gin. Without discipline the Sahib might easily find himself at the end of a day's march with perhaps only half his loads. It was a slow march this day; we had barely accomplished 8 miles, when Bullock and I with the hindmost came round a shoulder on the right bank about 4 p.m. and found the tents pitched on a grassy shelf and looking up a valley where a stream came in from our left. The Tibetan headman and his Tibetan coolies who were carrying some of our loads had evidently no intention of going further, and after some argument I was content to make the stipulation that if the coolies (our own as well as the Tibetans) chose to encamp after half a day's march, they should do a double march next day.

The prospect was far from satisfactory: we were at a valley junction of which we had heard tell, and the headman pointed the way to the left. Here indeed was a valley, but no glacier stream. It was a pleasant green nullah covered with rhododendrons and juniper, but presented nothing that one may expect of an important valley. Moreover, so far as I could learn, there were no villages in this direction: I had counted on reaching one that night with the intention of buying provisions, more particularly goats and butter. Where were we going and what should we find? The headman announced that it would take us five more days to reach Chomolungma: he was told that he must bring us there in two, and so the matter was left.

If the coolies behaved badly on this first day, they certainly made up for it on the second. The bed of the little valley which we now followed rose steeply ahead of us, and the path along the hill slopes on its left bank soon took us up beyond the rhododendrons. We came at last for a mid-day halt to the shores of a lake. It was the first I had seen in the neighbourhood of Everest; a little blue lake, perhaps 600 yards long, set on a flat shelf up there among the clouds and rocks, a sympathetic place harbouring a wealth of little rock plants on its steep banks; and as our present height by the aneroid was little less than 17,000 feet, we were assured that on this Eastern side of Everest we should find Nature in a gentler mood. But we were not satisfied with our direction; we were going too much to the South. Through the mists we had seen nothing to help us. For a few moments some crags had appeared to the left looming surprisingly big; but that was our only peep, and it told us nothing. Perhaps from the pass ahead of us we should have better fortune.

At the Langma La when we reached it we found ourselves to be well 4,000 feet above our camp of the previous night. We had followed a track, but not always a smooth one, and as we stayed in hopes of a clearing view, I began to wonder whether the Tibetan coolies would manage to arrive with their loads; they were notably less strong than our Sherpas and yet had been burdened with the wet heavy tents. Meanwhile we saw nothing above our own height. We had hoped that once our col was crossed we should bear more directly Westward again; but the Tibetan headman when he came up with good news of his coolies, pointed our way across a deep valley below us, and the direction of his pointing was nearly due South. Everest, we imagined, must be nearly due West of Kharta, and our direction at the end of this second day by a rough dead reckoning would be something like South-west. We were more than ever mystified. Fortunately our difficulties with the coolies seemed to be ended. Two of our own men stayed at the pass to relieve the Tibetans of the tents and bring them quickly on. Grumblings had subsided in friendliness, and all marched splendidly on this day. They were undepressed with the gloomy circumstance of again encamping in the rain.