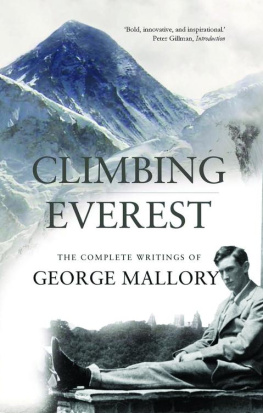

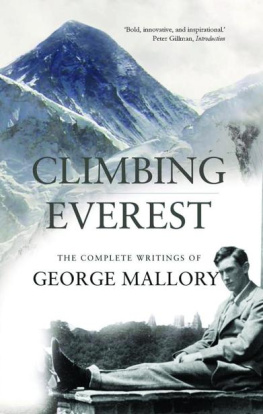

As a matter of history it has been stated already in an earlier chapter of this book that the highest mountain in the world attracted attention so early as 1850. When we started our travels in 1921, something was already known about it from a surveyor's point of view; it was a triangulated peak with a position on the map; but from the mountaineer's point of view almost nothing was known. Mount Everest had been seen and photographed from various points on the Singalila ridge as well as from Kampa Dzong; from these photographs it may dimly be made out that snow lies on the upper part of the Eastern face at no very steep angle, while the arete bounding this face on the North comes down gently for a considerable distance. But the whole angle subtended at the great summit by the distance between the two of these view-points which are farthest apart is only 54 deg.. The North-west sides of the mountain had never been photographed and nothing was known of its lower parts anywhere. Perhaps the distant view most valuable to a mountaineer is that from Sandakphu, because it suggests gigantic precipices on the South side of the mountain so that he need have no regrets that access is barred in that direction for political reasons.

The present reconnaissance began at Kampa Dzong, no less than 100 miles away, and in consequence of misfortunes which the reader will not have forgotten was necessarily entrusted to Mr. G. H. Bullock and myself, the only representatives of the Alpine Club now remaining in the Expedition. It may seem an irony of fate that actually on the day after the distressing event of Dr. Kellas' death we experienced the strange elation of seeing Everest for the first time. It was a perfect early morning as we plodded up the barren slopes above our camp and rising behind the old rugged fort which is itself a singularly impressive and dramatic spectacle; we had mounted perhaps a thousand feet when we stayed and turned, and saw what we came to see. There was no mistaking the two great peaks in the West: that to the left must be Makalu, grey, severe and yet distinctly graceful, and the other away to the rightwho could doubt its identity? It was a prodigious white fang excrescent from the jaw of the world. We saw Mount Everest not quite sharply defined on account of a slight haze in that direction; this circumstance added a touch of mystery and grandeur; we were satisfied that the highest of mountains would not disappoint us. And we learned one fact of great importance: the lower parts of the mountain were hidden by the range of nearer mountains clearly shown in the map running North from the Nila La and now called the Gyanka Range, but it was possible to distinguish all that showed near Everest beyond them by a difference in tone, and we were certain that one great rocky peak appearing a little way to the left of Everest must belong to its near vicinity.

It was inevitable, as we proceeded to the West from Kampa Dzong, that we should lose sight of Mount Everest; after a few miles even its tip was obscured by the Gyanka Range, and we naturally began to wonder whether it would not be possible to ascend one of these nearer peaks which must surely give us a wonderful view. I had hopes that we should be crossing the range by a high pass, in which case it would be a simple matter to ascend some eminence near it. But at Tinki we learned that our route would lie in the gorge to the North of the mountains where the river Yaru cuts its way through from the East to join the Arun.

From Gyanka Nangpa, which lies under a rocky summit over 20,000 feet high, Bullock and I, on June 11, made an early start and proceeded down the gorge. It was a perfect morning and for once we had tolerably swift animals to ride; we were fortunate in choosing the right place to ford the river and our spirits were high. How could they be otherwise? Ever since we had lost sight of Everest the Gyanka Mountains had been our ultimate horizon to the West. Day by day as we had approached them our thoughts had concentrated more and more upon what lay beyond. On the far side was a new country. Now the great Arun River was to divulge its secrets and we should see Everest again after nearly halving the distance. The nature of the gorge was such that our curiosity could not be satisfied until the last moment. After crossing the stream we followed the flat margin of its right bank until the cliffs converging to the exit were towering above us. Then in a minute we were out on the edge of a wide sandy basin stretching away with complex undulations to further hills. Sand and barren hills as beforebut with a difference; for we saw the long Arun Valley proceeding Southwards to cut through the Himalayas and its western arm which we should have to follow to Tingri; and there were marks of more ancient river beds and strange inland lakes. It was a desolate scene, I suppose; no flowers were to be seen nor any sign of life beyond some stunted gorse bushes on a near hillside and a few patches of coarse brown grass, and the only habitations were dry inhuman ruins; but whatever else was dead, our interest was alive.

After a brief halt a little way out in the plain, to take our bearings and speculate where the great mountains should appear, we made our way up a steep hill to a rocky crest overlooking the gorge. The only visible snow mountains were in Sikkim. Kanchenjunga was clear and eminent; we had never seen it so fine before; it now seemed singularly strong and monumental, like the leonine face of some splendid musician with a glory of white hair. In the direction of Everest no snow mountain appeared. We saw the long base tongues descending into the Arun Valley from the Gyanka Range, above them in the middle distance an amazingly sharp rock summit and below a blue depth most unlike Tibet as we had known it hitherto. A conical hill stood sentinel at the far end of the valley, and in the distance was a bank of clouds.

Our attention was engaged by the remarkable spike of rock, a proper aiguille. As we were observing it a rift opened in the clouds behind; at first we had merely a fleeting glimpse of some mountain evidently much more distant, then a larger and clearer view revealed a recognizable form; it was Makalu appearing just where it should be according to our calculations with map and compass.

We were now able to make out almost exactly where Everest should be; but the clouds were dark in that direction. We gazed at them intently through field glasses as though by some miracle we might pierce the veil. Presently the miracle happened. We caught the gleam of snow behind the grey mists. A whole group of mountains began to appear in gigantic fragments. Mountain shapes are often fantastic seen through a mist; these were like the wildest creation of a dream. A preposterous triangular lump rose out of the depths; its edge came leaping up at an angle of about 70 deg. and ended nowhere. To the left a black serrated crest was hanging in the sky incredibly. Gradually, very gradually, we saw the great mountain sides and glaciers and aretes, now one fragment and now another through the floating rifts, until far higher in the sky than imagination had dared to suggest the white summit of Everest appeared. And in this series of partial glimpses we had seen a whole; we were able to piece together the fragments, to interpret the dream. However much might remain to be understood, the centre had a clear meaning as one mountain shape, the shape of Everest.