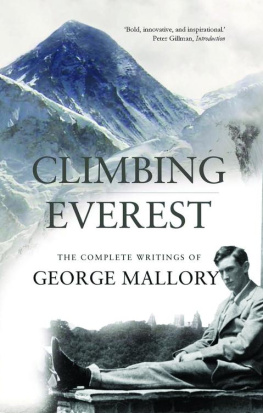

Mount Everest has been my arena. I have spent over two years of my life on the mountain, returning there again and again. I am drawn back because I see there the extremes of human experience played out in the most dramatic surroundings: greed and betrayal, loyalty and courage, endurance and defeat. It is a moral crucible in which we are tested, and usually found wanting. It has cost me my marriage, my home and half my possessions. Twice Everest has nearly killed me. But I find it utterly addictive. And so did George Mallory.

This volume is going to add to the vast pile of books about Mount Everest, a pile that must now must be higher than the mountain. I make no apology for this, for I think I have finally solved the mystery of what happened there on 8 June 1924, when Mallory and his young companion Sandy Irvine disappeared into clouds, climbing strongly towards the top.

My family had a unique relationship with Everest, and this helped me to climb the mountain and to find clues to what happened to Mallory, its most famous opponent. I spent a long time looking for his body, and then I spent a long time trying to prove that he climbed his nemesis before it killed him.

This is going to be a personal story, a detective thriller, a biography and a history book.

I hope it will set the record straight about how Mallory was found. It is about other things, too, such as why we believe in gods and mountains.

Most of all, though, it is about my life-long hunt for an answer to the greatest mystery in mountaineering: who first climbed Mount Everest?

Dawn broke fine on that fatal day. A couple of thousand feet above the tiny canvas tent the summit of the worlds highest mountain stood impassively, waiting for someone to have the courage to approach.

Inside the ice-crusted shelter, two forms lay as still as death. Then there was a groan, a stirring, and eventually the slow scratch of match against sandpaper. Low voices shared the high-altitude agonies of waking, the heating of water and the struggle with frozen boots.

As the sun rose through wisps of cloud beyond the Tibetan hills to the east, one of the men emerged through the tent flaps. It was a fine morning for the attempt, with only a few clouds in the sky. The two of them stood for a while, shuffling their feet and blowing into their hands. Inside the tent lay a mess of sleeping bags and food. The men lifted oxygen sets onto their backs, then turned towards the mountain and stamped off into history.

Seventy years later, above the Hillary Step on the other side of the mountain, I was teetering along the narrow icy summit ridge between Nepal and Tibet, between life and death. The sun was intensely bright and the sky was that deep blue-black of very high altitudes. All around were the icy fins of the worlds highest mountains. And somewhere along that ridge I experienced one of those existential moments that gives you the reason for gambling with your life. The intenseness of the now, the sharp savour of living wholly in the present moment: no past, no worries. The chop of the ice axe, the crunch of the crampons, the hiss of breath this is the very essence of life. Eventually I saw a couple of figures just above me, a couple of steps and I was there.

I cant remember much. Now it all seems a sort of vivid dream: bright sunlight, a tearing wind, a long flag of ice particles flying downwind of us. A vast drop of two miles into Tibet. We could see across a hundred miles of tightly packed peaks, and we could see the curvature of the earth. Contorted faces shouting soundlessly, lips blue with oxygen starvation. Doctors prove with blood samples that climbers are in the process of dying up there on the summit, but I would say that is where I started to live.

As I stumbled down the mountain one thought kept recurring to me. If I, a very average climber, could stand on this summit, how could the legendary George Mallory have failed to do so?

1

Mountaineering is in my blood. My father started taking me out into the hills of Arran when I was five, and I can still remember the moment when we scrambled to the top of the islands highest mountain. I saw the sea laid out almost three thousand feet beneath us like a polished steel floor. Down there was Brodick Bay, with the ferry steaming in from the mainland like a toy boat.

Climbing was filled with sensation: the sheer agony of panting up steep slopes in the summer sun, the sharp smell of my fathers sweat as we lay resting in the heather, the hard coldness of a swim in the burn. Then the gritty feel of the granite under your fingers, and the blast of wind in your face as you breasted the summit.

It must have been a double-edged pleasure for my father, though. His brother, John Hoyland had been killed on Mont Blanc in 1934. Jack Longland, a famous climber of the day who was on the 1933 Everest expedition, described John as potentially the best mountaineer of his generation there was no young English climber since George Mallory of whom it seemed safe to expect so much.

John had hoped to go on the next expedition to Everest, but his death at the age of nineteen had put paid to those hopes. Even I could feel the loss at thirty years distance.

My father told me about another climbing hero in our family, a man who had been close to the summit of Mount Everest in 1924. He called him Uncle Hunch, and Dad said that one day I would meet him. He said hed been a close friend of George Mallory, and again that name was mentioned. Mallory, the paragon of climbers. My young mind took it all in.

I lived and dreamed mountains on those summer holidays. To me Goat Fell, the highest of the Arran hills, looked uncannily like Mount Everest when viewed from the south; indeed it does to me even now. And it is almost exactly a tenth of Everests height. I remember cricking my neck back and back on the Strabane shore and trying to count out ten Goat Fells standing on top of each other. I couldnt imagine anything so impossibly vast. How could anyone climb so high?

Eventually, when I was 13 and he was 81, I met Uncle Hunch.

We were at the memorial service of my great-aunt Dolly, who was one of the Quaker Cadburys. She was wealthy and lived in a large country mansion. I remember her house had a wide, open, red-carpeted spiral staircase for the family, inside of which was an enclosed stone staircase for the servants. I would race up the outer stairs past glass-cased model steam engines and then clatter down the inner, hidden stairs. We, the poor relations, used to receive a huge box of Cadburys chocolates every Christmas from Aunt Dolly, and I was particularly fond of her for her gentleness and the P. G. Wodehouse books she used to pass on to me.

Her death was a shame, I thought, a further distancing from a more romantic past. But oddly enough, I was about to be more firmly connected with that past.

I remember standing on the lawn outside Verlands and looking up at Uncle Hunch the legendary Howard Somervell, who was actually a cousin, not an uncle.

He really was an extraordinarily gifted man: a double first at Cambridge, a talented artist (his pictures of Everest are still on the walls of the Alpine Club) and an accomplished musician (he transcribed the music he heard in Tibet into Western notation). He served as an army surgeon during the First World War and was one of the foremost alpinists of the day when he was invited to join the 1922 Mount Everest expedition. He took part in the first serious attempt to climb the mountain, and his oxygen-free height record stood for over 50 years. General C. G. Bruce, the expedition leader, described his strength on the mountain: Stands by himself an extraordinary capacity for going day after day.