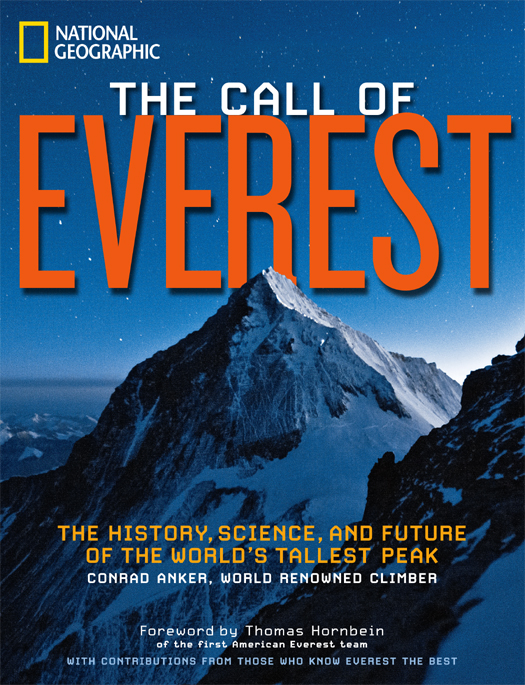

The National Geographic Society is one of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to increase and diffuse geographic knowledge, the Societys mission is to inspire people to care about the planet. It reaches more than 400 million people worldwide each month through its official journal, National Geographic, and other magazines; National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; music; radio; films; books; DVDs; maps; exhibitions; live events; school publishing programs; interactive media; and merchandise. National Geographic has funded more than 10,000 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program promoting geographic literacy. For more information, visit www.nationalgeographic.com.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE

(647-5463) or write to the following address:

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact

National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights:

Copyright 2013 National Geographic Society.

Foreword, Everest Calls, text 2013 Thomas Hornbein

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Anker, Conrad.

The call of Everest : the history, science, and future of the worlds tallest peak /

Conrad Anker; foreword by Thomas Hornbein.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-4262-1241-3

1. Everest, Mount (China and Nepal) 2. Mountaineering expeditions-Everest, Mount (China and Nepal)History. 3. Everest, Mount (China and Nepal)Description and travel. I. Hornbein, Thomas. II. Title.

DS495.8.E9A64 2012

915.496dc23

2012045336

v3.1

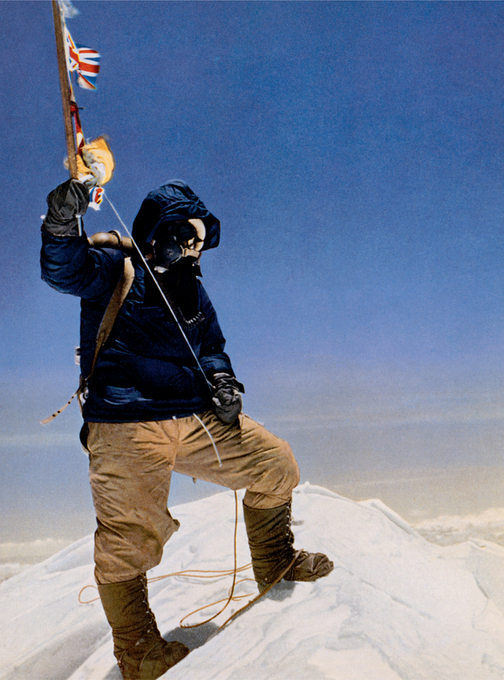

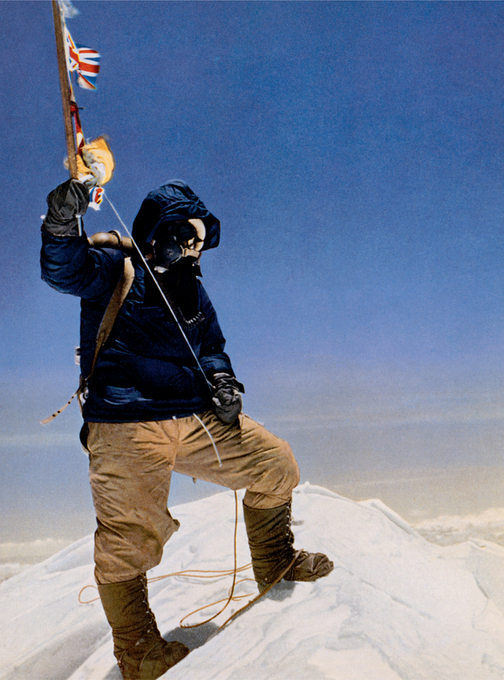

SUCCESS! TENZING NORGAY holds out his ice ax into the thin air on the summit of Mount Everest on May 29, 1953, as he and Edmund Hillary became the first people to stand at the summit.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

EVEREST CALLS

Thomas Hornbein

CHAPTER 1

THE MEANING OF EVEREST

Conrad Anker

CHAPTER 2

THE BIRTH OF EVEREST

David R. Lageson

CHAPTER 3

THE PEOPLE OF EVEREST

Broughton Coburn

CHAPTER 4

THE NATURE OF EVEREST

Alton C. Byers

CHAPTER 5

THE CLIMBERS OF EVEREST

Bernadette McDonald

CHAPTER 6

THE AGONIES OF EVEREST

Bruce D. Johnson

CHAPTER 7

ONE SEASON ON EVEREST

Mark Jenkins

CHAPTER 8

THE FUTURE OF EVEREST

David Breashears

A SCOUTING PARTY during the 1963 American Mount Everest Expedition appears as small figures in the foreground of Everests forbidding West Ridge. The group inspects part of a new route that will be used by Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein to reach the summit.

In the spring of 2012 the National Geographic Society and The North Face sponsored the Legacy Expedition to Everest. Its goal and that of a companion expedition sponsored by Eddie Bauer was to revisit the 1963 American Mount Everest Expeditions journey nearly half a century before, with teams ascending from both the South Col route and the West Ridge. The plan, like ours in 1963, was to meet on the summit, with the West Ridge climbers descending, as did Willi Unsoeld and I, by the South Col route. Though the South Col part of this plan succeeded during one of the two brief windows of tolerable weather, excessive rockfall and poor snow conditions on the West Ridge made it too hazardous. This years was not an uncommon experience; the success rate on this route over the past half century has been around 10 percent of about 60 attempts, and the chances of dying have proved to be about the same as those of reaching the summit.

This book, The Call of Everest, also celebrates that same 50th anniversary of the first American expedition to climb Everest (and also the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay). This volume is a natural for the National Geographic Society, which was a major supporter of the 1963 American Mount Everest Expedition (AMEE), not least because of the participation of one of their own, Barry Bishop, who was on the team both as climber and photographer. His photo of two tiny figures, Willi Unsoeld and me, on the crest of the West Shoulder, dwarfed by the mountain soaring seductively above captures for me the essence of what our West Ridge adventure was aboutsavoring uncertainty.

The AMEE was successful almost beyond our wildest dreams. On May 1 Jim Whittaker, along with Sherpa Nawang Gombu, became the first American to summit Everest. Three weeks later four more followed. Lute Jerstad and Barry Bishop topped out by the South Col route midafternoon on May 22. A tad tardy, at 6:15 p.m. Willi and I completed the first ascent of the West Ridge (via what Willi liked to refer to as Hornbeins avalanche trap, now known as the Hornbein Couloir). We headed down the South Col route, catching up with Lute and Barry, and we four finished it all off sitting out the night together above 28,000 feet in an unintended bivouac. We were very lucky to have survived the night and lucky that Willi and I had been able to pull off the first traverse of a major Himalayan peak.

Our ascent of a new route on Everest was a predictable stage in the evolution of humankinds relationship with mountains. The underlying theme of this quest is to perpetuate uncertainty: First we identify a goal worthy of our dreams, then figure out how to get to its base, and finally seek a way to its top. Once the mountain has been conquered (an abominable term), the next challenge is to find new paths to follow. This stage also begins to encompass style and, on Everest in particular, climbing without the aid of supplemental oxygen. Later in this evolution new uncertainties are added, like skiing or parachuting from the summit to be down in time for tea. Inevitably, as the human-mountain relationship reaches maturity, the advent of guided climbing brings less experienced aspirants to enjoy a taste of ultimate adventure.

Though none of this evolution is unique to Everest, what is unique is the explosion in numbers seeking to be guided to the top of the highest point on Earth. Everest is being loved to death. But its not the mountain thats dying.

I must admit that until the events of the 2012 season, and in spite of the tragedy of 1996 and some subsequent years, I was able to rationalize the growing numbers and pragmatically accept that guided climbing was as inevitable on Everest as on every other attractive mountain in the world. I reckoned that less experienced but fit people could be guided up Everest with a reasonable margin of safety. I was impressed that the mortality rate did not go up despite the increased numbers of novices. I attributed this relative success to the strategies adopted by thoughtful guide services working together, for example fixing ropes over any terrain where a fall could carry you off.