ALSO BY WADE DAVIS

The Wayfinders

Light at the Edge of the World

The Clouded Leopard

Shadows in the Sun

One River

The Serpent and the Rainbow

Passage of Darkness

The Lost Amazon

The Sacred Headwaters

Nomads of the Dawn

(with Ian MacKenzie and Shane Kennedy)

Rainforest

(with Graham Osborne)

Book of Peoples of the World

(ed., with David Harrison and Catherine Howell)

Grand Canyon

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by Wade Davis

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

All photographs courtesy of Royal Geographical Society except (top and middle): Ed Webster.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Davis, Wade.

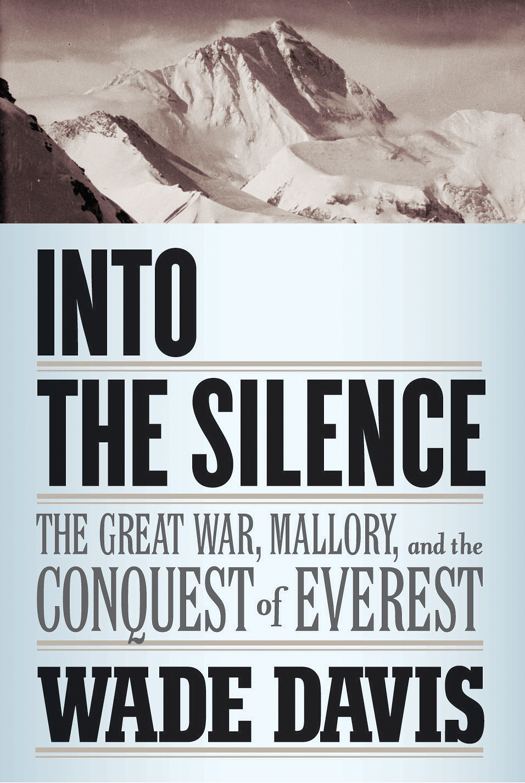

Into the silence : the Great War, Mallory, and the conquest of Everest / by Wade Davis.1st ed.

p. cm.

A Borzoi book.

1. Mallory, George, 18861924. 2. Mountaineers

Great BritainBiography. 3. Mount Everest Expedition

(1924). 4. World War, 19141918Great Britain

Influence. I. Title.

GV199.92.M356D38 2011

796.522092dc22

[ B ] 2011013888

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Davis, Wade

Into the silence : the Great War, Mallory, and the conquest of

Everest / Wade Davis.

Includes bibliographical references.

Also issued in electronic format.

eISBN: 978-0-307-40185-4

1. Mallory, George, 18861924. 2. Mountaineering expeditions

Everest, Mount (China and Nepal). 3. Mountaineers

Great BritainBiography. 4. SoldiersGreat Britain

Biography. 5. Everest, Mount (China and Nepal). 6. World War,

19141918Great Britain. I. Title.

GV199.92.M34D39 2011 796.522092 C2011-901741-5

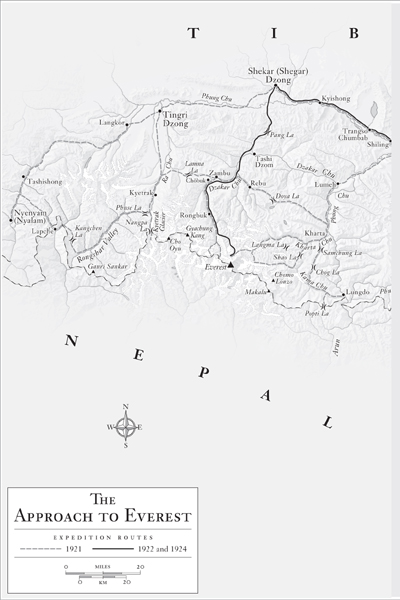

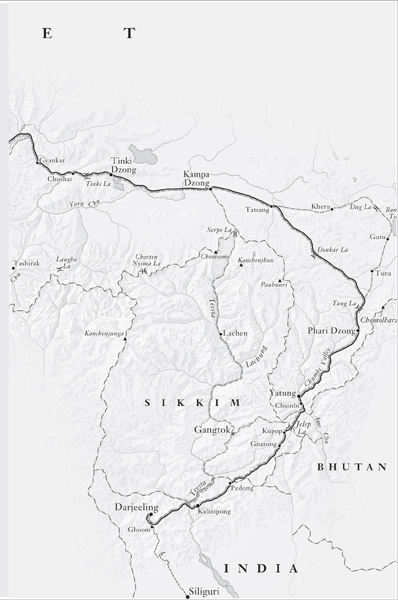

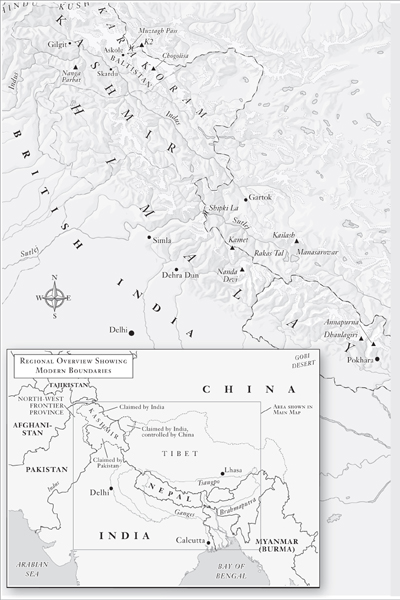

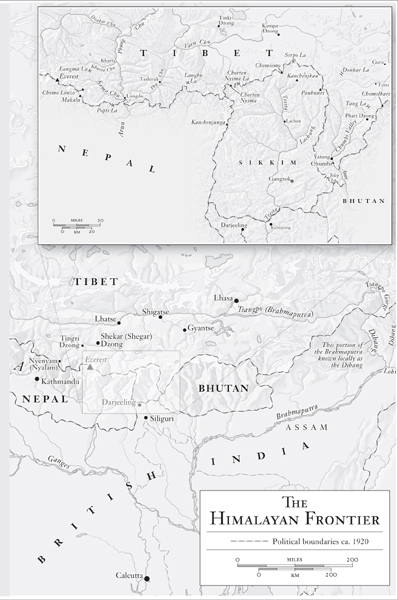

Maps by David Lindroth, Inc.

Cover image: Mount Everest from the North East by L.V. Bryant, 1935 Royal Geographical Society

Cover design by Barbara de Wilde

v3.1

To my grandfather Captain Daniel Wade Davis, who served as a medical officer in France with the Royal Army Medical Corps, 80th Field Ambulance, 32nd Division Train, 19151916, and in England with the Canadian Army Medical Corps, 19161918

Contents

Preface

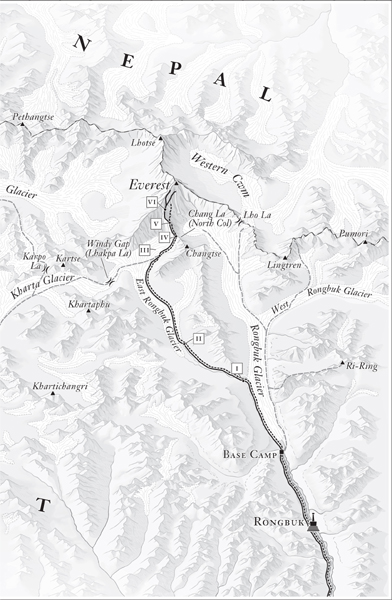

O N THE MORNING OF J UNE 6, 1924, at a camp perched at 23,000 feet on an ice ledge high above the East Rongbuk Glacier and just below the lip of Everests North Col, expedition leader Lieutenant Colonel Edward Norton said farewell to two men about to make a final desperate attempt for the summit. At thirty-seven, George Leigh Mallory was Britains most illustrious climber. Sandy Irvine was a young scholar of twenty-two from Oxford with little previous mountaineering experience. Time was of the essence. Though the day was clear, in the southern skies great rolling banks of clouds revealed that the monsoon had reached Bengal and would soon sweep over the Himalaya and, as one of the climbers put it, obliterate everything. Mallory remained characteristically optimistic. In a letter home, he wrote, We are going to sail to the top this time and God with us, or stamp to the top with the wind in our teeth.

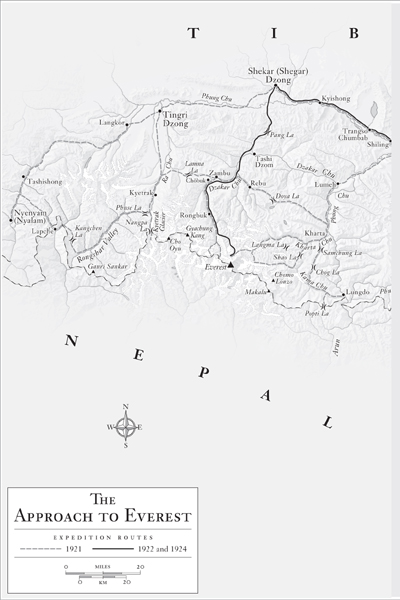

Norton was less sanguine. There is no doubt, he confided to John Noel, a veteran Himalayan explorer and the expeditions photographer, Mallory knows he is leading a forlorn hope. Perhaps the memory of previous losses weighed on Nortons mind: seven Sherpas left dead on the mountain in 1922, two more this season, the Scottish physician Alexander Kellas buried at Kampa Dzong during the approach march and reconnaissance of 1921. Not to mention the near misses. Mallory himself, a climber of stunning grace and power, had, on Everest, already come close to death on three occasions.

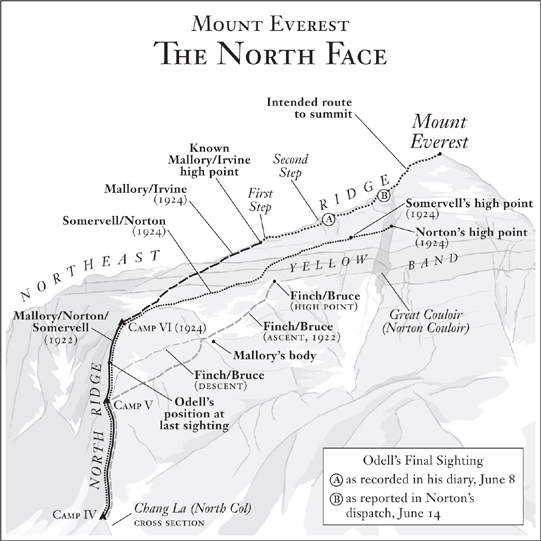

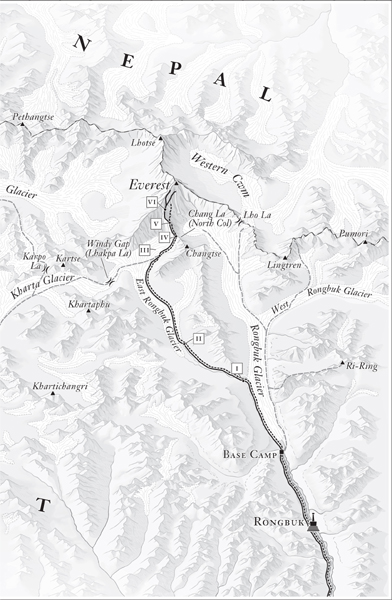

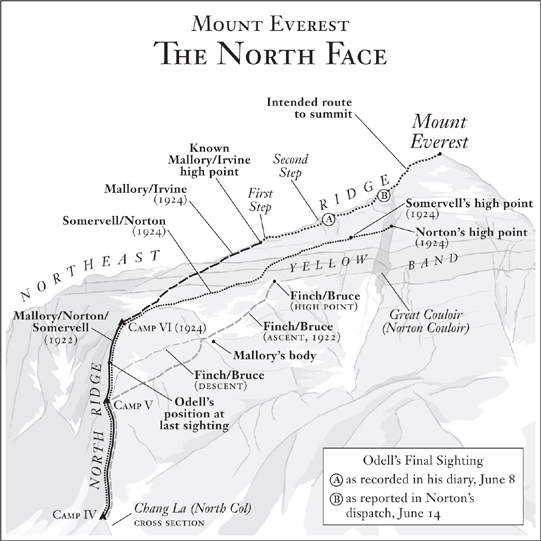

Norton knew the cruel face of the mountain. From the North Col, the route to the summit follows the North Ridge, which rises dramatically in several thousand feet to fuse with the Northeast Ridge, which, in turn, leads to the peak. Just the day before, he and Howard Somervell had set out from an advanced camp on the North Ridge at 26,800 feet. Staying away from the bitter winds that sweep the Northeast Ridge, they had made an ascending traverse to reach the great couloir that clefts the North Face and falls away from the base of the summit pyramid to the Rongbuk Glacier, ten thousand feet below. Somervell gave out at 28,000 feet. Norton pushed on, shaking with cold, shivering so drastically he thought he had succumbed to malaria. Earlier that morning, climbing on black rock, he had foolishly removed his goggles. By the time he reached the couloir, he was seeing double, and it was all he could do to remain standing. Forced to turn back at 28,126 feet, less than 900 feet below the summit, he was saved by Somervell, who led him across the ice-covered slabs. On the retreat to the North Col, Somervell himself suddenly collapsed, unable to breathe. He pounded his own chest, dislodged the obstruction, and coughed up the entire lining of his throat.

By morning Norton had lost his sight, temporarily blinded by the sunlight. In excruciating pain, he contemplated Mallorys plan of attack. Instead of traversing the face to the couloir, Mallory and Irvine would make for the Northeast Ridge, where only two obstacles barred the way to the summit pyramid: a distinctive tower of black rock dubbed the First Step, and, farther along, the Second Step, a 100-foot bluff that would have to be scaled. Though concerned about Irvines lack of experience, Norton had done nothing to alter the composition of the team. Mallory was a man possessed. A veteran of all three British expeditions, he knew Everest better than anyone alive.

Two days later, on the morning of June 8, Mallory and Irvine set out from their high camp for the summit. The bright light of dawn gave way to soft shadows as luminous banks of clouds passed over the mountain. Noel Odell, a brilliant climber in support, last saw them alive at 12:50 p.m., faintly from a rocky crag: two small objects moving up the ridge. As the mist rolled in, enveloping their memory in myth, he was the only witness. Mallory and Irvine would not be seen or heard from again. Their disappearance would haunt a nation and give rise to the greatest mystery in the history of mountaineering.