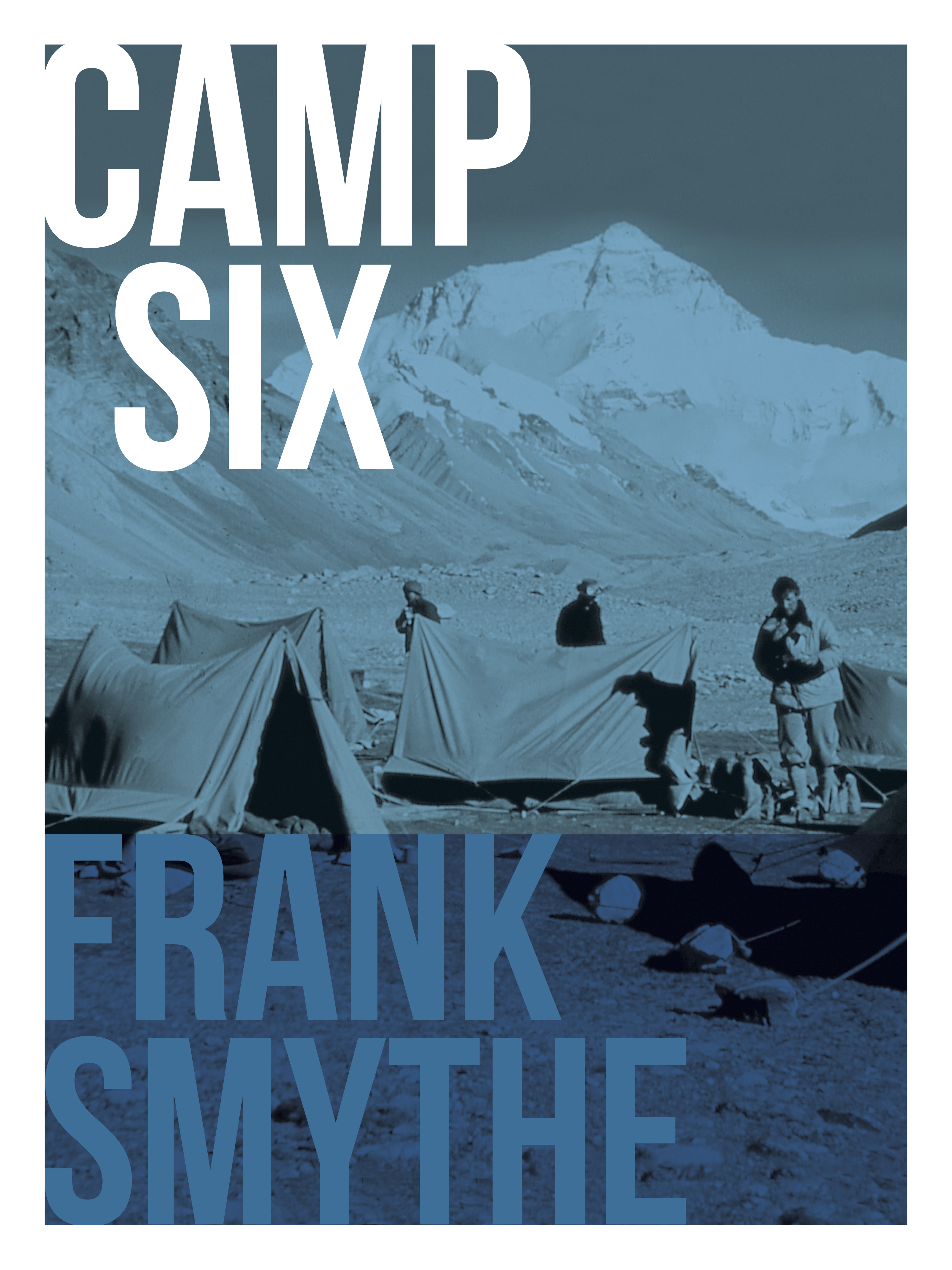

Authors Note

This book is a personal account of the 1933 Everest Expedition, compiled from a diary which accompanied me to the highest camps, and is published by permission of the Mount Everest Committee. The reader who desires a more comprehensive account is referred to the official expedition book Everest 1933 by Hugh Ruttledge.

There have been six expeditions to Everest of which two were primarily reconnaissances and there is to be a seventh in 1938. The 1933 Expedition was the fourth and, like the 1924 Expedition, it came very near to success. Its members were:

Hugh Ruttledge (leader) [Hugh], E.O. Shebbeare [Shebby], C.G. Crawford [Ferdie],

Captain E.St.J. Birnie [Bill]; Maj. Hugh Bousted [Hugo]; T.A. Brocklebank [Tom];

Dr. C. Raymond Greene, Percy Wyn Harris [Wyn], J.L. Longland [Jack], Dr. W. McLean

[Willy], Eric E. Shipton, Lieut.W.R. Smijth-Windham [Smidge]; F.S. Smythe, Lieut.

E.C. Thompson [Tommy], Lawrence R. Wager [Waggers], George Wood-Johnson.

The memories of physical hardship are fortunately so illusive that it almost seems to me that my diary exaggerates. Did we really have such an unpleasant time in 1933? Perhaps in this connection I may mention the diary of a former Everest climber. Above the Base Camp his description of the days events is said to be prefaced invariably by the words Another bloody day.

It is instinctive with man to want to dominate his environment and Everest is one of the last great problems left to him on the surface of this Earth. In solving this problem he adds to his scientific knowledge, and enjoys a physical and spiritual adventure.

That Everest will be climbed cannot be doubted; it may be next year or a generation hence. Every expedition adds to our knowledge of the problem, yet, in the end, the climber depends for success on the casting vote of fortune. There are three problems inherent in the ascent. Firstly, the difficulty of the mountain, which is considerable at a height of 28,000 feet; secondly, the altitude and, thirdly, the weather. Skill and knowledge may solve the first two, but the last will always remain an incalculable factor. The weather defeated the 1933 and 1936 expeditions, though it remains to be proved that men can live in the rarefied air above 28,000 feet without some artificial aid.

Lastly, no reference to the Everest problem, however brief, is complete if it fails to mention the Sherpa and Bhotia porters. Their work has brought us very near to success, and the story of their courage and devotion should stand out in letters of gold when the last chapter in the struggle comes to be written.

Publishers Note

The disappearance of Mallory and Irvine in 1924 and the discovery of the ice axe in 1933, make Camp Six and the official account (Everest, 1933) of particular value. These carried the assessments of what might have happened in 1924 by the first climbers to revisit the scene. Their opinions may be more focused than those of modern commentators as they had similar equipment, food, fuel, and tactical perceptions as the 1924 climbers. Frank Smythe suggests, in the postscript, the ice axe position may point to an accident that took place during the ascent. The later discovery of what may have been a carefully stashed (rather than discarded) oxygen bottle apparently beyond (towards the summit) the ice axe site may weaken this theory. In 1999 the discovery of Mallorys roped body, suggested that he was linked to Irvine at the moment of mishap. This has, if anything, made the presence of the ice axe even more puzzling as the body and axe sites are a considerable distance apart, albeit generally in line. These more recent discoveries are of relevance to the debate in this book, so additional footnotes (denoted by ) have been added where suitable.

Chapter One

Darjeeling

Calcutta is hot even in February. Though sorry to part from many hospitable friends, I was glad to begin the last stage of my journey from England to Darjeeling.

It was a stuffy night to begin with in the Darjeeling Mail, and ravenous mosquitoes interfered with my slumbers, but towards dawn the temperature fell and cool, refreshing airs rushed in at the window.

As the train neared Siliguri the sky lightened with a quick rush of rosy tints and little pools of water opened calm eyes in the paddy fields of the Bengal plain.

I peered from the window into the dim hill-filled north, and there, high up in the sky, I saw a tiny point of golden light. During the few seconds that it was visible before a curve took it from sight it grew larger. It was the summit of Kangchenjunga, nearly one hundred miles distant.

At Siliguri, the foothills meet the plain, and the hillman the plainsman. Half of those on the platform were languid Bengalis, the other half energetic, slant-eyed, broad-faced, high-cheeked Tibetans; smooth-skinned, quiet-mannered Lepchas from Sikkim, and tough little Sherpas from Nepal, their brows furrowed as though from the strain of staring into great distances, and their eyebrows puckered from the snow-glare of the passes. Traders, beggars, Lama pilgrims, rickshaw wallahs from Darjeeling and little Nepali women from the tea plantations, with gay-coloured blouses and cone-shaped wicker baskets on their backs; all were cheerful, all ready to show their teeth in a broad grin.

I breakfasted, then ascended to Darjeeling by the world-renowned Himalayan Railway. So wide are the carriages that they seem likely to over-balance on the narrow-gauge line. A brave little engine draws the train, but it would not succeed in climbing the steeper gradients without two men stationed on the front to pour sand on the rails.

First along the plain, fussed the train, then into the sub-tropical forests that extend for scores of miles along the foothills of the Himalayas. One minute, we were on the level, the next we were climbing steeply uphill.

After the placid, less secretive beauties of English woodlands, these Himalayan forests are strangely impressive. Sunlight rarely penetrates their dense foliage, beneath which all manner of rank shrubs struggle despairingly upwards towards the sunlight; giant creepers embrace the moss-clad trees in an octopus-like grip, and epiphytic ferns, proof of the humid climate, hang from the branches in lank green tendrils, so that the traveller fancies himself walking on an ocean floor amid pendent masses of seaweed. In each great tree dwells a colony of birds and insects, and there is a constant whirring and humming as though countless sewing machines and sawmills were being worked by invisible hands.

Pantheists who can see only beauty and gentility in nature should visit a tropical or sub-tropical forest. Grossness and strife are the keynotes, and the predominant motif is death and the fear of death. Much has been written of the gentle beauties of the English countryside, but where are the poets of the jungle?

The train stopped to pick up a red-haired Irishman, who told me that he had been sitting up all night for a tiger, but without success. He also related the providential escape of a friend from an infuriated leopard. The would-be leopard killer fired one barrel of his gun he was using a double-barrelled shotgun firing soft-nosed bullets and missed. The other cartridge misfired. The next moment the leopard was on him. He ducked as it sprang and somehow he was a powerful man threw the beast over his shoulder. The leopard was so surprised at this all in treatment that it made off, leaving the hunter with a badly mauled arm which he subsequently lost through sepsis. The story ended romantically; he married his nurse.