Pen & Sword Discovery

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard Sale and George Rodway 2011

ISBN 978-1-84884-139-0

ePub ISBN: 9781844683192

PRC ISBN: 9781844683208

The right of Richard Sale and George Rodway to be identified as

Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

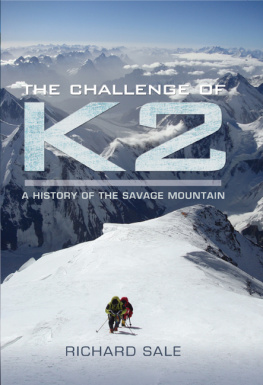

Cover photograph: Tom Hornbein on the summit after the first ascent

of Everests West Ridge in 1963. ( Willi Unsoeld Estate)

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics

and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Prologue

On 20 July 1939 two men lay outside the tent they had pitched, enjoying the warmth of the summer sun. So warm was it that the men lay naked on their sleeping bags. Apart, perhaps, from the nudity, there is little in this picture to surprise. But the tent the two had pitched was at 7940m, just 671m below the summit of K2, the second highest mountain in the world. The two men were Fritz Wiessner and Pasang Dawa Lama, and the previous day they had climbed to within about 240m of the summit.

Fritz Wiessner was born in Dresden in 1900 and emigrated to the United States in 1929, by which time he had established himself as a superb rock climber: at the age of 25 he had completed one climb in the Austrian Tyrol that was claimed to have been the hardest yet accomplished in the European Alps at that time. In the US he rapidly produced a string of climbs which raised the standard of American rock climbing. It was therefore no surprise that in 1939 he was invited to go to the Karakoram.

The Americans had already attempted to climb K2 in 1938, when an expedition under the leadership of Charles Houston had, in the course of a thorough reconnaissance of the mountain, identified the most promising line, up the Abruzzi Ridge. One member of the team, Bill House, climbed what proved to be a crucial chimney that allowed access to the peaks upper slopes, but the team was forced to retreat from a high point of 7925m.

The original plan had been for the 1938 expedition to be led by Wiessner, but he was unable to participate because of other commitments. So, when a new attempt was scheduled for 1939, he was the logical choice for leader. He chose a strong team of American alpinists but for various reasons many dropped out, and the party he eventually led was inexperienced. Nevertheless they made good progress and by 18 July Camp IX had been established at 7940m, below K2s final pyramid. Here Wiessner and Pasang Dawa Lama, the strongest of the teams Sherpas, spent the night.

Wiessner scanned the route above the camp for a line to the top. There were two options. One moved right to gain a snow corridor that led diagonally to the top. The second option was to tackle a rock headwall, taking its left edge which appeared to lead to the final summit snow slopes. Wiessner was concerned about the threat posed by the huge ice cliffs overhanging the first route, and as a rock climber he was naturally drawn to the second line. So on 19 July the two men, using no supplementary oxygen, set out for the rock wall. It was 9am, a late start very late indeed by modern standards and ice on the rocks slowed the progress of master rock climber Wiessner. But he persevered, and by 6pm had arrived at a point from where he could see that only a final rock pitch separated him and Pasang Dawa Lama from easy-angled snow slopes. Wiessner reckoned that another 3 or 4 hours of snow trudging would see the pair on the summit. The two men were not too exhausted and the weather was set fair so, despite the novelty of the idea, Wiessner saw no problem in continuing to the top and descending through the night.

But Pasang Dawa Lama would have none of it. In his account Wiessner comments that, with nightfall approaching, the Sherpa had lost heart for the climb and refused to continue. Later accounts, apparently based on conversations with Pasang, have suggested he was fearful of the revenge the mountain gods might exact for the two mens temerity in advancing on their citadel in darkness.

The two men therefore descended, safely but not without incident: at one point, as Pasang extracted himself from a tangle of ropes, he lost the pairs crampons. It was 2.30am on 20 July when the two reached camp, which was one reason why Wiessner decided to rest that day. A leisurely breakfast and a laze in the sun would restore their energies, ready for another attempt the next day. But on 21 July the climb did not go well. Wiessner this time took the snow corridor. Without crampons, steps needed to be cut in the snow and Wiessner knew he had neither the time nor the energy to do so. The pair retreated to Camp IX and the next day climbed down to Camp VIII. By now Pasang Dawa Lama was exhausted, but Wiessner was determined to have one more attempt with a different companion and so left his sleeping bag at Camp IX.

At Camp VIII the retreating climbers found none of the supplies they had anticipated and, much worse, they found Dudley Wolfe, who had been alone in the camp for five days. With no matches to light a cooker, Wolfe had had little to eat and had only been able to drink water melted by the sun on his tents fabric.

Dudley Wolfe was 44 years old, heavy and clumsy, a rich socialite with limited mountaineering experience, all of it as a guided climber whose guides tended to have to haul his corpulent frame up the hill. His presence on the expedition can be put down entirely to his wealth, which underwrote the trip. But he shared Wiessners dream of reaching the top of K2. That dream and his cash had allowed Wolfe to avoid much of the effort the others had put into climbing the mountain. He did no lead climbing and when not climbing upwards seems to have spent his time in his sleeping bag.

The lack of supplies at Camp VIII meant Wiessner was forced to descend further. The three men took a heavy fall on the way and then, to their dismay, found that one tent at Camp VII was wrecked, the other collapsed. Worse still, the camp had been almost completely cleared of equipment. The three men were forced to share a single sleeping bag Wolfe having lost his in the fall and spent a miserable night. Next day Wiessner and Pasang Dawa Lama descended to Camp VI to fetch supplies, leaving Wolfe at Camp VII. Exactly why Wolfe was left behind is not clear, but it was a decision that would have dramatic consequences, as the two who went down found that every camp on the mountain had been stripped. Not until they reached Base Camp, utterly exhausted, could they get proper food and rest.

Wolfe was left at Camp VII on the morning of 23 July. Rescuers did not reach him until noon on the 29th. By then he was in a pitiful state, having had little to eat or drink. He had not left the tent once, using it as a toilet rather than leave the comfort of his sleeping bag for too long. He could not be persuaded to go down, telling the Sherpas who reached him to come back the next day when he would be ready to move; with no option but to obey, the Sherpas descended. Two days later three Sherpas (Pasang Kikuli, Ang Kitar and Pintso) again climbed up in an effort to rescue Wolfe. Neither he nor the Sherpas were ever seen again.

Next page