Winter Mountaineering is the fourth book in the Rucksack Guide series and covers the skills required to become a competent winter mountaineer. This handy book can be kept in your rucksack and will help you to gain the experience to mountaineer safely in winter anywhere in the world. It does not cover the technical aspects of navigation or alpinism (see Rucksack Guides to Mountain Walking and Trekking and Alpinism).

The Rucksack Guide series tells you what to do in a situation, but it does not always explain why. If you want more information behind the decisions in these books, go to Mountaineering: The Essential Skills for Mountaineers and Climbers by Alun Richardson (A&C Black, 2008).

For more information about the author, his photographs and the courses he runs go to:

www.alunrichardson.co.uk.

On a cold clear day, with firm snow, winter mountaineering can be safer than in summer. However, it can all change in a few hours and gale force winds, blizzards, zero visibility, avalanches and the numbing cold will soon sap your reserves.

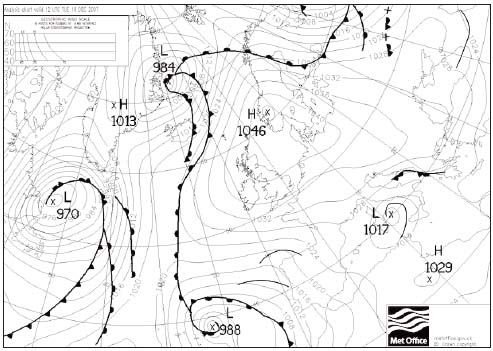

Winter starts as the sun drops on the horizon and the Earth is warmed less effectively. In the Northern Hemisphere this allows the Polar Front to move south bringing colder air from the Arctic. From autumn, through winter and well into spring, the battle between the warmer moist air to the south, and the colder drier air to the north, produces the winter storms that bring the snow to the UK and North America. (See Mountaineering: The Essential Skills for Mountaineers and Climbers (A&C Black, 2008) or Rucksack Guide: Mountain Walking and Trekking (A&C Black, 2009) both by the author, for more information on how our weather is made).

The low pressure gradient within winter storms often creates strong winds of 160kph plus. Gusts of 70kph and above are difficult to walk in and the wind above 800m, especially in Scotland, is at least double the strength at sea level. The wind chill factor can make it feel even colder: +5C in a 50kph wind can feel like 12C on exposed flesh. The mountains in winter are serious places.

EXPERT TIP |

|

| Alun Richardson IFMGA/BMG Guide www.alunrichardson.co.uk Dont let blind ambition ruin your winter trip. The mountains will always be there will you? |

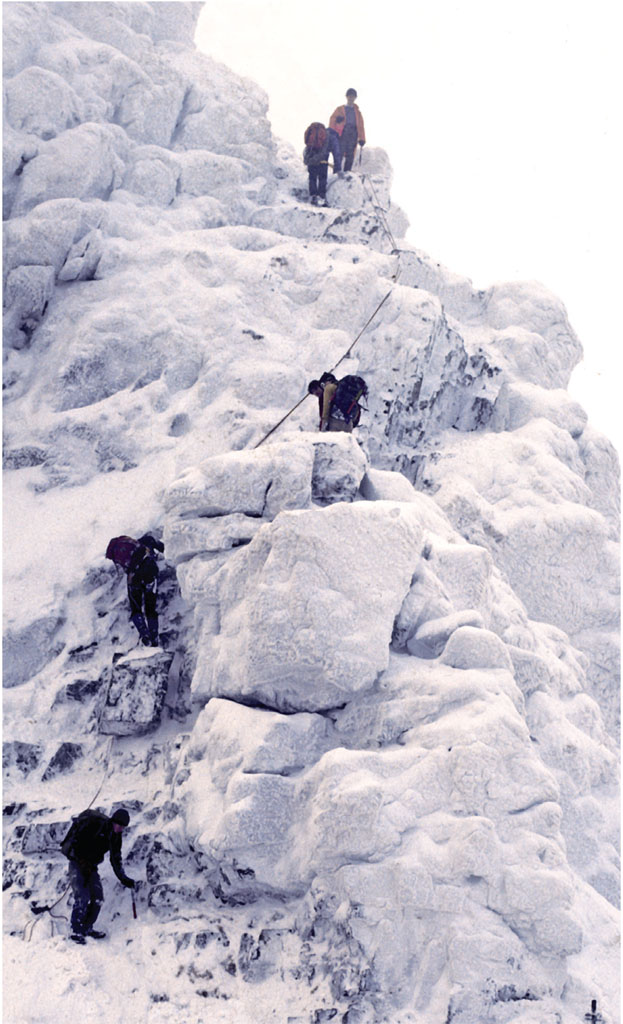

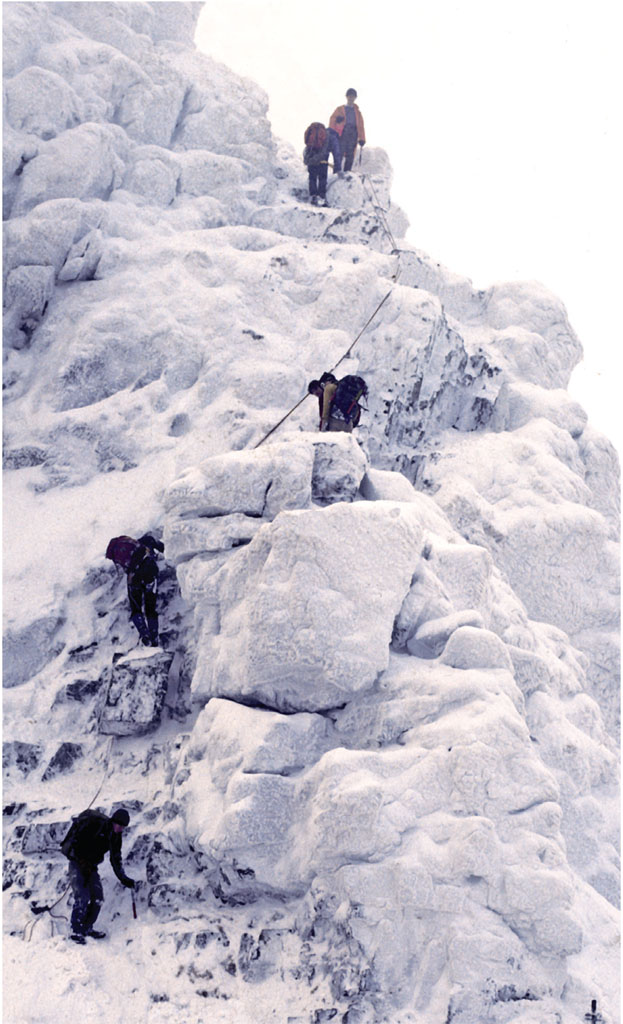

Aanoch Eagach traverse, Glencoe, Scotland

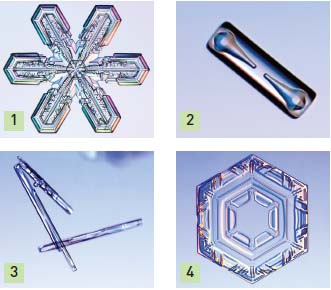

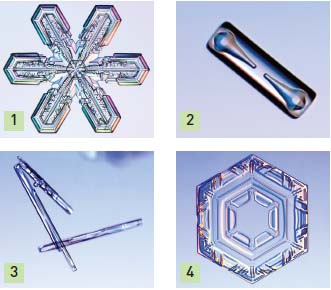

When the temperature of a cloud falls below 0C, tiny particles, such as bits of clay, encourage water to turn into ice crystals that then combine to form snowflakes.

A snowflake is a number of snow crystals that join together as they fall through air that is close to freezing. When the temperature is ideal for stickiness, and the wind is light enough not to break them up, the flakes can grow very large.

Varying temperature, moisture and wind conditions favour crystal growth in different ways ():

Stellar crystals (1) The classic star-shaped snowflake

Columns (2) New snow crystals in a six-sided hollow or solid prism

Needles (3) Long, thin forms

Plates (4) Thin, usually hexagonal crystals

Graupel Soft hail created by water droplets that freeze to crystals forming round particles

Ice pellets Form when rain falls through a very cold air mass

Fig. 1Snow crystal formations

There are two ways air can rise in winter:

When warm, moist air is lifted over cold air it cools, forming clouds, rain or snow. The warmer the air, the more moisture it contains, and the faster it rises and cools, the greater the snowfall. Therefore, air masses originating in warmer areas, such as the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans, have a tendency for greater snowfall.

However, just because a cloud contains snow does not mean it will land as snow rain, freezing rain, sleet and snow can all fall on the same place as the front moves overhead.

When warm air extends to ground level, the snow melts and falls as rain (most winter rain is actually melted snow).

If the band of cold air is relatively thin and the ground is below freezing, the falling rain cools and turns into ice when it hits something, causing freezing rain.

When the layer of cold air is thick enough, the falling rain freezes into ice pellets. If the snow can fall all, or most, of the way through cold air, it falls as snow. At very cold temperatures snowflakes do not form and the snow mostly comprises snow crystals.

If the snowflakes fall and rise again, they can melt and refreeze forming hailstones.

Sleet is a soft melted snowflake that has refrozen.

Although frontal lifting is the major cause of summer storms, in winter the mountains themselves have a major effect. As a storm front, or even just moist air, reaches the mountains it is forced upwards (orographic lift). The resulting cooling can then form snow. The rate of lifting depends on the steepness of the mountains and is greater when the air mass hits the mountain range straight on.

To identify possible snowstorms, look for the path of the depression and its associated fronts:

What is its origin? Does it contain moisture?

Is it travelling over cold areas and can it pick up moisture?

Is the air dry and cold? Since water vapour is needed to make clouds and snow, cold air will tend to produce lighter snow than warmer air, which is why a years worth of snow at the South Pole melts down to less than 8cm of water. In general, the heaviest snow usually falls when the temperature is only a little below freezing, or even above freezing at ground level.

Is the air mass hitting the mountains straight on?

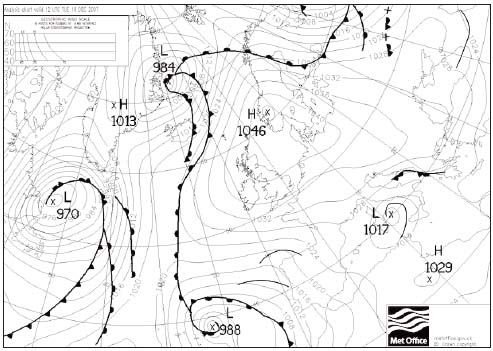

Fig. 2A winter weather map, Crown Copyright (2008), the Met Office. In this example the UK is experiencing sunshine and light winds from an anticyclone. A developing polar low north of Iceland will bring cold polar air and some snow from the moisture it picks up over the sea.

COLD CLEAR SPELLS |

|

High pressure established over Northern Europe or the US during winter can bring a spell of cold easterly or northerly air streams to the UK or US. The clear skies, settled conditions and light winds associated with high pressure allow heat to be lost from the surface of the Earth. The temperature then falls overnight, leading to air or ground frosts. Fog can also form, because the winds are light. |