Alpinism is the sixth book in the Rucksack Guide series and covers the skills required to become a competent alpine mountaineer. This handy book can be kept in your rucksack and will help you to gain the experience to mountaineer safely anywhere in the world. Many of the skills required for competent alpinism are the same as traditional rock climbing and winter mountaineering. This book does not cover the technical aspects of navigation, rock, snow and ice climbing (see Rucksack Guides to Mountain Walking and Trekking, Rock Climbing and Winter Mountaineering for further information).

The Rucksack Guide series tells you what to do in a situation, but it does not always explain why. If you want more information behind the decisions in these books, go to Mountaineering: The Essential Skills for Mountaineers and Climbers by Alun Richardson (A&C Black, 2008).

For more information about the author, his photographs and the courses he runs go to:

www.alunrichardson.co.uk.

Alpinism is not controlled adventure like sport climbing or climbing on a roadside crag; it is real adventure, in which you have to rely more on your awareness and judgement than your technical skills. Luckily there are challenges to suit everyones ambitions, experience and abilities, including glacial walking, non-technical and technical routes on low- or high-altitude mountains.

A non-technical peak can be described as one where one axe will suffice, yet the ascent requires fitness and an understanding of objective dangers such as altitude, rock fall and avalanche. General crampon, ice axe and rope work skills are required for crossing glaciers and ascending easier snow slopes. A technical peak usually involves all of the above, as well as scrambling, rock-climbing and/or ice climbing techniques.

Alpinism refers to mountaineering in areas such as the Rocky Mountains, the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada in the United States, and the Canadian Rockies. For UK climbers, the European Alps are a useful stepping-stone to expedition climbing, because the mountains are more remote, logistics are difficult and rescue is largely down to the climbers themselves.

Many of the skills required for competent alpinism are the same as traditional rock climbing and winter mountaineering or climbing. They are applied here to the European Alps, but the principles also apply to alpine mountain ranges around the world.

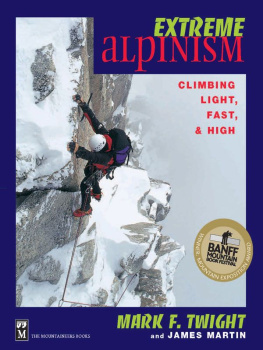

Fig. 1Climbers on Peigne dArolla, Swiss Alps

Climbing quickly is the essence of safe alpinism, as you are exposed to the danger zone for less time, and it enables you to reach the summit and descend before the afternoon storms catch you. Being fit and a good climber are obvious assets, but efficiency is synonymous with climbing light if you carry everything you are probably going to need it!

Unlike Scotland in winter, you will experience extremes of temperature in the same day, meaning a flexible clothing system is essential. Invest in a good pair of Schoeller-type mountaineering trousers and always carry a warm hat and gloves. Consider shorts and a T-shirt for the walk to the hut. Wear combinations of layers and ventilate/remove the layers to stay dry.

Next to the skin Use a performance wicking fabric, such as polypropylene, that wicks perspiration away from your skin to the mid-layer. Avoid cotton.

Mid-layer Use a thicker synthetic fleece to hold in the heat.

Insulating layer A thicker fleece or a soft shell jacket is ideal for the summer. A light down jacket is a good idea for high mountain trips.

Waterproof layer Most of the time the weather will be good, so use lightweight waterproof shells for emergency protection.

EXPERT TIP |

|

| Richard Mansfield IFMGA Mountain Guide www.mountain-guides.net Climbing lightweight: light, plus light, plus light equals heavy. |

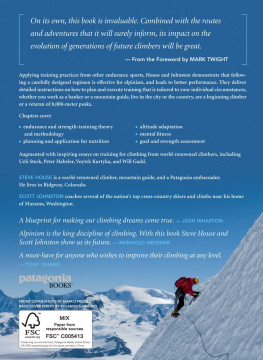

Fig. 2You can save weight on nearly every piece of kit, from krabs to your rucksack. (Climbers on Monch Bernese Oberland, Switzerland.)

Boots suitable for alpine use will have room for your toes to wriggle, be stiffer and have a sharp edge to the sole for kicking into snow slopes. You can wear a pair of running shoes for the hut walk (leave them at the hut if you are coming back the same way).

BOOT TYPES |

Type | Pro | Con |

Leather boots | Good for climbing mixed routes in less-than Arctic conditions Provide a more precise feel | Not as warm Less waterproof |

Plastic boots | Provide warmth Provide good support for ice climbing Waterproof | Mostly heavier Less sensitive The shells cover two size ranges, with a thicker inner to pad out the smaller size. This collapses over time. |

To make the issue of boot/crampon compatibility more straightforward, boots and crampons can be graded according to their basic design and intended use. However, not all manufacturers follow the system designed by Scarpa ().

Graded B0 to B3, dependent on the stiffness of the sole and the support provided by the uppers:

B0 Flexible walking boots. Any boot that can be bent more than half an inch when standing on the front edge will be less suitable for use with all crampon types.

B1 Stiff mountain walking boots suitable only for use with C1 crampons (see ).

B2 Very stiff mountaineering boots suitable only for use with C1 or C2 crampons.

B3 Fully rigid, winter climbing and mountaineering boots suitable for use with C1, C2 or C3 crampons.

Fig. 3A sturdy pair of boots with room for your toes to wriggle is essential for warmth and stability on snow.

Feet have little muscle bulk and it is much easier to keep them warm than to warm them up.

On long belays, avoid standing on snow, weight your feet equally and stamp your feet when they start to chill.

Try to minimise the body closing down the extremities by dressing according to the route and climate, and don't scrimp on leg protection.

Keep your feet dry, even if it means changing your socks during the day.

Wear gaiters (see ).

Foot powder with aluminium hydroxide can help to reduce perspiration.