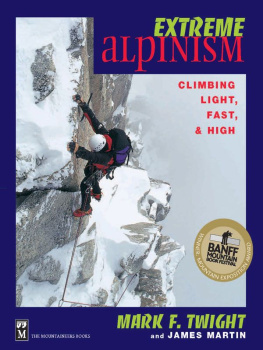

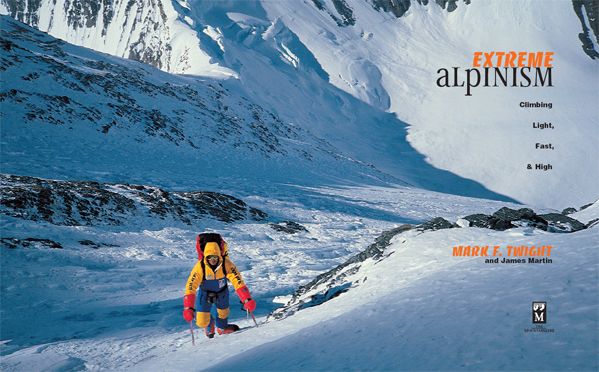

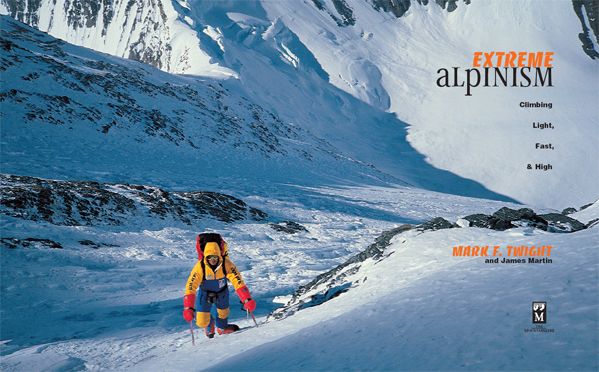

EXTREME

alpinism

Climbing Light, Fast, & High

Twight has been one of Americas boldest climbers for a couple of decades, and his book is a primer for serious mountaineers.

The Twin Falls, ID Times-News

| Published by The Mountaineers Books 1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201 Seattle, WA 98134 |

1999 by Mark Twight and James Martin

All rights reserved

First printing 1999, second printing 2000, third printing 2001, fourth printing 2003, fifth printing 2004, sixth printing 2006, seventh printing 2008, eighth printing 2012

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distributed in the United Kingdom by Cordee, www.cordee.co.uk

Manufactured in China

Edited by Don Graydon

Cover and book design by Ani Rucki

Layout by Ani Rucki

Cover photographs: Front: Mark Twight on the Arte des Cosmiques, Chamonix, France. Photo: James Martin. Back: Mark Twight on the Aiguille du Midi, Chamonix, France. Photo: James Martin

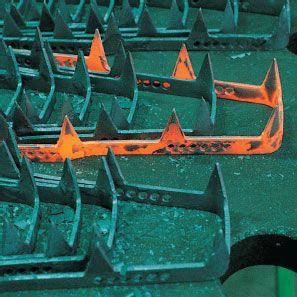

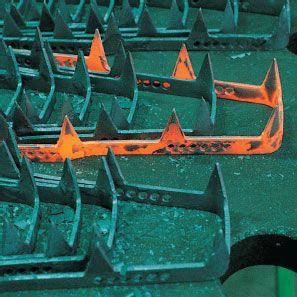

Frontispiece: Crampons cooling in the Grivel factory in Courmayeur, Italy. Photo: Mark Twight

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Twight, Mark, 1961

Extreme alpinism : climbing light, fast, and high / Mark Twight and James Martin. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-89886-654-5 (pbk.)

1. Mountaineering. 2. MountaineeringTraining. 3. MountaineeringPsychological aspects. I. Martin, James, 1950 II. Title.

GV200.T95 1999

ISBN (paperback): 978-0-89886-654-4

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-59485-383-8

F or my mentors: I owe you everything.

Strategy is beyond the techniques.

Technique is beyond the tools.

One.

Two.

Ten thousand.

CONTENTS

Scott Backes climbing near the top of the fourth rock band during the first ascent of Deprivation on the North Buttress of Mount Hunter, Alaska. Photo: Mark Twight

FOREWORD

In June 1977, I had the incredible good fortune to climb in the Alaska Range with two of my personal heroes, Jeff Lowe and George Lowe. Four thousand feet up a new route on the north face of Mount Hunter, Jeff rode a broken cornice for sixty feet, snagged a crampon, and cracked his ankle. Somewhat naive and certainly far less experienced than these titans of the North American alpine climbing scene, I viewed this development with considerable alarm, while my more worldly companions seemingly took it in stride.

In reality, the level of concern Jeff and George had for our predicament equaled or exceeded mine. They simply had so many more miles than I did that they knew exactly how to deal with it. I had the technical skills, but each of them had the head. It was an invaluable lesson, but I would learn a lot more in the coming weeks.

We worked out an efficient system for our retreat and reached the glacier a day and a half later. Jeff flew out to have his ankle treated, and after a few days rest, George and I returned to the face and completed the Lowe-Kennedy and a descent of the West Ridge in a five-day round trip. Mount Hunter had been a big route, especially for me, but now George and I were faced with a difficult decision. We had originally planned to go for yet another first ascent, but with Jeff, who we both felt was the strongest member of our team, out of action, we struggled with our doubts and fears. What if we came up against something we couldnt climb? What if George or I were injured? Most important, could the two of us, alone, put out the sustained physical and psychological effort needed for our next project, the south face of Mount Foraker?

Unlike Hunter, which was largely a snow-and-ice climb, Foraker would involve mostly technical rock and mixed climbing on a longer route on a higher peak. After reaching the mountains south summit, wed have to traverse to the higher north summit, and then descend the treacherous Southeast Ridge. Nothing quite like it had been done alpine-style in Alaska before.

After much discussion, we decided to go to the Cassin Ridge, the classic hard route on Denali. The route had been climbed many times before, and we both felt confident in doing it. But doubts swirled around in my head, and fifteen minutes before leaving, I told George that we should go to Foraker instead. I thought that wed always question ourselves if we didnt take this step into the unknown.

We made the long approach that night, and spent most of the next day resting and observing the face, guessing at where wed go, how far wed get each day, where we might encounter problems. An early-morning dash across the serac-threatened glacier put us onto the route, the line revealing itself as we worked our way up the initial rock pitches.

After our second night on the route itself, we knew we didnt have enough gear to rappel down the ground wed already covered. The only way out was up and over the top. Foraker was the first time Id experienced this level of commitment, and it was a marvelously liberating experience. We had been apprehensive starting up the route, but as we gained elevation the doubts and fears gradually faded away as we became more and more immersed in the climbing, the details of eating, drinking, and sleeping in this steep, apparently inhospitable world.

On our fifth day, near the end of twenty-four hours of continuous climbing, we came to the hardest part of the route, a steep mixed gully. George suggested that we bivouac so wed be able to tackle the problem fresh, but I had a second (or third or fourth) wind and went ahead.

What remains is one of my most powerful climbing memories. I recall very little of the actual climbing, the technical details of the moves. What I do remember is looking up and visualizing myself climbing this sectionwhich was probably the hardest climbing of that sort Id done at the timeand then some time later, looking back down at George as he came up. It is one of the few times Ive gone outside my own consciousness, beyond what I thought or knew I could do, a feeling that Ive kept looking for since, in climbing, skiing, running, hiking, all the mountain activities were so fortunate to enjoy. As befits such a rare gift, it has always come unheralded, never when I thought it would or should.

We continued to the top and back down, with a few exciting moments along the way. George and I had spent eleven of the most intense and rewarding days of our lives on the Infinite Spur. Twenty-two years and many mountains later it remains my most influential climb, an experience that opened my eyes to the possibilities in the big mountains of the world. But as much as anything, Foraker awakened in me a deep sense of spirituality and reverence for life that has helped define my life since then.

Like so many who started climbing in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I began as a hiker, soon took up rock climbing, and eventually gravitated toward the mountains. Ive never taken a climbing lesson or been to a climbing school. I learned from friends, taught myself a lot, and served a lengthy apprenticeship under the guidance of more accomplished climbers. My education continues, as does my shedding of decades-old bad habits and weaknesses.

Next page