Copyright 2014 by Andrew Lock

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First North American Edition 2015

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

Visit the authors website at www.Andrew-Lock.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lock, Andrew, 1969

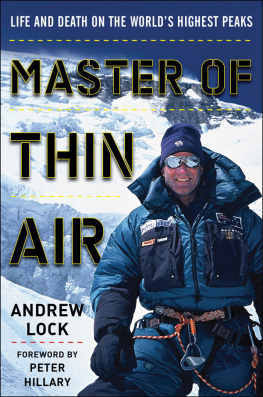

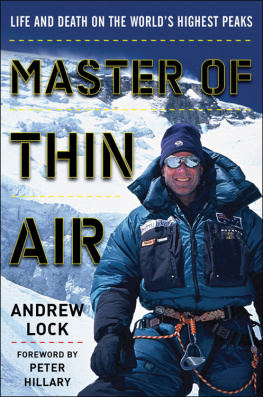

Master of thin air : life and death on the world's highest peaks / Andrew Lock ; foreword by Peter Hillary.First North American edition.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-62872-573-5 (hardcover : alk. paper); 978-1-62872-616-9 (E-book)

1. Mountaineering. 2. Lock, Andrew, 1969- 3. MountaineersBiography. I. Title.

GV200.L67 2015

796.522092-dc23

[B]

2015013992

Cover design by Andrew Lau

Cover photo: www.Andrew-Lock.com

To my mother, who for over twenty years stoically waved me goodbye, then acted as my personal assistant, answering my mail and paying my bills, all the time waiting for the dreaded phone call that said there was no point paying them any more.

To those genuinely passionate climbers who followed their dreams purely for the spirit of the adventure but did not survive to tell their own stories and whose losses in great numbers have gone largely unnoticed.

To three specific individuals, and all those like them in Scouts and other volunteer organisations, who give their time to inspire and develop the youth of Australia: Adrian Cooper OAM, who introduced me to the thrill of outdoor adventuring; Bob King, who nurtured my outdoor passion through leadership and guidance; and Geoff Chapman, whose altruism and unceasing belief in me enabled and motivated me to keep going.

Thank you, all.

THE 8000ERS

T here are fourteen peaks in the world whose tops reach above 8,000 metres (26,247 feet), and it is these that mountaineers refer to as the 8000ers. The altitude into which they tower is so extreme that it is known as the death zone, where climbers must reach their goal and descend in a matter of hours before their bodies shut down and they literally die from thin air.

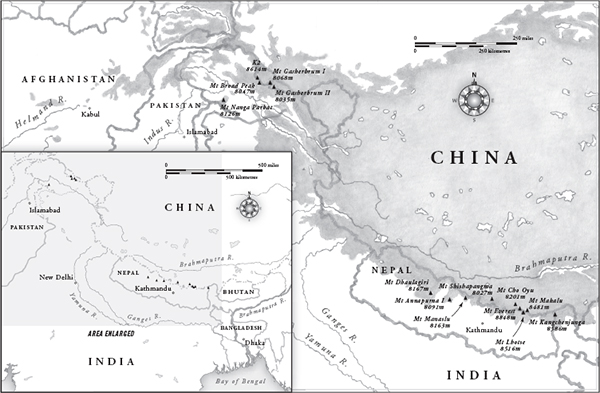

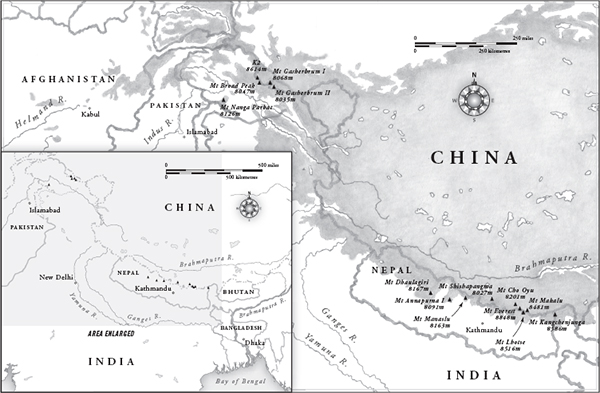

The 8000ers are not to be confused with the Seven Summits, which are the highest peaks on each of Earths seven continents. Everest is one of those seven summitsit is the highest mountain on the continent of Asiabut the rest of the seven summits are lower than 7,000 metres (22,966 feet) and as low as 2,200 metres (7,218 feet), in the case of Mt. Kosciusko in Australia. The 8000ers are all to be found in the Himalayan and Karakorum mountain ranges of South AsiaIndia, Nepal, Tibet, China and Pakistan. The most westerly 8000er, Nanga Parbat, stands just above Pakistans Indus valley and the most easterly, Kanchenjunga, sits 2,400 kilometres (about 1,500 miles) to the southeast, just above Darjeeling on Nepals eastern border with India.

FOREWORD

M ountaineering is an apex sport and as Hemingway apparently put it, all the others are merely games. So where do mountaineers go to reach the pinnacle of their sport? The incomparable Himalayas.

The worlds fourteen highest mountains all exceed the 8,000-metre mark (or just over 26,000 feet) and they are all in the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges of Pakistan, China and Nepal. They are by far the tallest mountains on the planet. Shards of stone pushed higher than all the rest by extraordinary tectonic forces. Everest leads the pack by a commanding 250 metres over K2. (By comparison North Americas highest mountain, Mount McKinley, is 6,194 metres (20,322 feet) and 2,600 metres lower than Everest.) For mountaineers these huge Himalayan peaksKanchenjunga, Nanga Parbat, K2, Annapurnaare the stage where much dramatic history is acted out; they are the battle grounds of the conquistadors of the useless, as Lionel Terray aptly described his chosen pursuit.

By a strange quirk these great peaks that penetrate into the jetstream also coincide with the maximum physiological altitude that we humans can attain. In 1953, when my father and Tenzing first climbed Everest, the physiologists of the day debated whether it was even possible for humans to reach 8,800 metres (almost 29,000 feet). So why take the risk? George Mallory put it most simplyand perhaps most memorablywhen asked in 1924 during a press conference and a succession of mind-numbing questions about his motivations for why he would attempt to climb Mount Everest. Because it is there, he said. And while climbing it may be a human contrivance, its presence is as genuine and beckoning as the Atlantic was to Columbus. And now we all know we can achieve these goals and this knowledge opens the doors to individual possibility. You can go there too! If you have the grit and the blinkered focus.

Mountaineering in the modern era tackled issues to do with style and philosophy. Alpine style changed the mode of ascent more than anything before. Bold and purist teams of unsupported climbers pushed elegant lines up the great mountains without oxygen and logistical support. The great exponents of this development were people like Hermann Buhl, Reinhold Messner, Jerzy Kukuczka, Jean Troillet and Doug Scott, who made numerous astonishing climbs that changed the way mountaineers saw what was possible.

Interestingly, the current era in mountaineering has transformed substantially into everything from media stunts, commercially guided groups enabling ambitious CEOs to tag the top, speed ascents up prepared routes strung with rope, capsule style climbing, alpine style and bold solos by outstanding practitioners of Himalayan alpinism. You shouldnt judge the media reports from Mount Everest today as being typical of Himalayan climbing, as they are not and Andrews story illustrates this well. Today all these expeditions are equipped with satellite telephones and internet connections. These distractions have made Himalayan mountaineering more complex and less focused; more summit-driven and less interested in climbing excellence. There is nothing wrong with it, but the media soap operas are not the leading edge of the sport.

The popular seven summits (the highest peak on each continent) campaigns are, with the exception of Everest, more of an exciting adventure travelogue than a climbing-fest (and I completed the seven as a consolation prize when I couldnt complete all the 8000ers I wanted to climb). By comparison the small number of mountaineers who have climbed all the fourteen 8,000-metre peaks are the real thing. The leaders in this quest climbed their mountains by establishing new routes and pushed frontiers like no one had before. They were armed with superb technical skills, extensive alpine experience and an astonishing determinationReinhold Messner of Italy, Jerzy Kukuczka of Poland and Erhard Loretan of Switzerland. They showed us, on their separate expeditions, what could be accomplished. They are to mountaineers what the 8,000-metre peaks are to the Appalachian Mountains or the hills of Ben Nevis. They are giants.