Table of Contents

Guide

Copyright 2014 Liza Monroy

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Photo on page 293 by Kimberly Buchheit. Photo on page 296 by Judi Warehouse. All other personal photos are courtesy of the authors private collection. Every effort has been made to trace or contact all other copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Monroy, Liza.

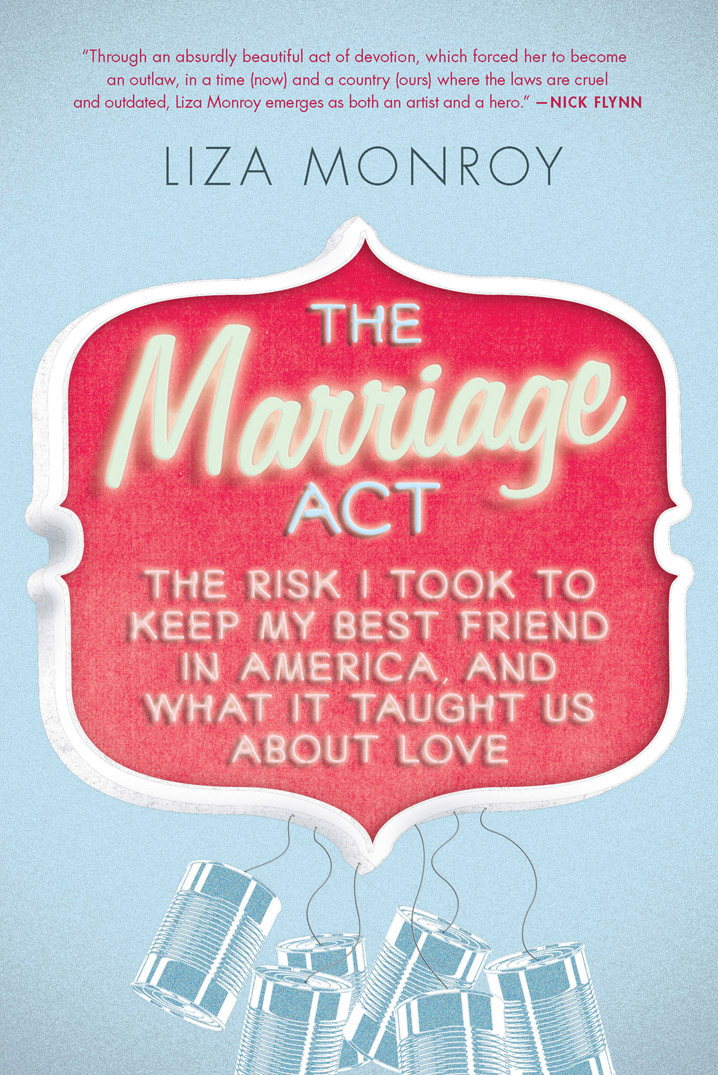

The marriage act : the risk I took to keep my best friend in America, and what it taught us about love / Liza Monroy.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61902-365-9

1. MarriageUnited States. 2. Matrimonial actionsUnited States. 3. Marriage lawUnited States. 4. Intercountry marriageUnited States. 5. AliensUnited States. 6. Gay menRelations with heterosexual women

I. Title.

HQ536.M545 2014

306.810973dc23

2013028275

Interior design by Sabrina Plomitallo-Gonzlez, Neuwirth & Associates

Cover design by Jennifer Heuer

Soft Skull Press

An Imprint of Counterpoint

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.softskull.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Emir

Contents

Memory is in this respect similar to anticipation: an instrument of simplification and selection.

Alain de Botton, The Art of Travel

Reality is the child of mans imagination.

Frigyes Karinthy, A Journey Round My Skull

One of the challenges in telling any personal story is reconciling faithfulness to fact with the subjective nature of individual perception. Sometimes, imagination invades even the surest of memories.

In this work, details of some events and identities have been changed in order to protect privacy, prevent deportation, and minimize the likelihood of anyones arrest.

Offering my hand in marriage to my close friend Emir had nothing to do with civil rights issues the night I got down on one knee in a crowded West Hollywood gay bar. I didnt do it as activism or to make a statement. Even though this act of marriage came to have political meaning in the aftermath, making a political gesture was not my intent. That came later. At the time, I proposed out of love, empathy, and support, along with desperation to keep Emir with me. All of it was done in secret. With a handful of exceptions, I didnt talk about it, and I certainly never imagined I would write a book coming out about it because our story had a place in a national conversation about equality, or that our story could further reveal the illogical underpinnings of why a debate ever existed in the first place.

At first, the story of Emir and me sounded mostly like a premise for one of the Hollywood movies I spent my days working on then, in my early twenties: Lost-but-Optimistic Young Woman Marries Her Gay Best Friendwho is from a Muslim family in the Middle Eastto keep him in the country, while her mother works for the State Department preventing immigration fraud. I used to refer to Emir and me as Will and Grace on steroids, but when gender-neutral marriage grew from niche to national issue in 2004, as Mayor Gavin Newsom of San Francisco began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, I realized that what I had taken to calling the book about us went beyond a romantic comedy with a catchy premise. Marrying Emir was, as with any marriage-type thing, a purely personal decision. Then again, The Personal Is Political and all.

When I decided to write about us, I thought I was writing a book about friendship. After all, what sustains the core of marriage if not friendship? But as I began writing, larger questions came to preoccupy me: What defines a union? What is a marriage? How can there be correct and incorrect love? Who is to say which loves are validvaluableand which are not? In writing The Marriage Act, I realized this personal narrative could highlight the absurdities of our marriage laws. How, in this century, is there still debate about gender discrimination? What it boils down to is that there are still second-class citizens in the United States today, and until gender-neutral marriage is legal federally, there will continue to be.

The irony is that while technically Emir and I fit into the proper gender classification of DOMA, The Defense of Marriage Actwhich defined marriage as between one man and one womanour marriage was, in actuality, less conventional, less traditional, than Emirs partnership with his true love, Stan (and the traditional familial love of millions of same-sex couples). It all leads to quite the quandary over the definition of marriage, and the absurdity of not granting federal marriage benefits to same-sex couples.

And yet, on another level, Emir and I were real. The surface reasons our marriage was illegitimate were that its main driving force was immigration, and that he is gay and I knew it when I married him. I wanted to marry him in spite of these things as much as because of them; even though I popped the question because he stood to be deported otherwise, even though he was gay, I wanted to marry him anyway. Marriage springs from emotion and emotions arent rational. With our history, deep emotional bond, and love of each other, Emir and I shared everything except sex. This blurry line came to highlight the ironies and problems of forbidding gender-neutral marriage on the federal level, of denying tens of thousands of couples the benefits that federal marriage providesimmigration of a foreign-born partner in particularsolely based on the couple being the same sex rather than opposite sexes. Now that DOMA has been done away with and Proposition 8 along with it, it looks as though the path has been cleared more so than before, but until same-sex marriage is federally recognized and available in every state, there is still a ways to go.

After the uproar leading to Proposition 8 resulted in nationwide attention to the debate over gender-neutral marriage, immigration entered the picture. Even in the fifteen states (as of this writing) where same-sex marriage is legal, if one partner is a U.S. citizen but not the other, the citizen is powerless to keep his or her partner in the country should the partner lose the legal ability to stay by other means, such as an H-1B work visa. Same-sex marriages are invisible on the federal level. So while I could marry Emir or even a man off the street and secure him a green card, couples with more traditional marriagesmonogamy and life devotion and even childrenhave been powerless to do the same. The consequences are devastating.

One such case was that of Bradford Wells and Anthony John Makk, a couple for nineteen years and counting. Makk is Australian and Wells is a U.S. citizen with health complications from AIDS. Makk, his caregiver, was threatened with deportation after being denied spousal immigration benefits, even though the couple lived in Massachusetts, where same-sex marriage is legal, because of DOMAwhich Bill Clinton signed into law in 1996, and which defined marriage on the federal level as existing solely between one man and one woman.

At first, the San Francisco Chronicle