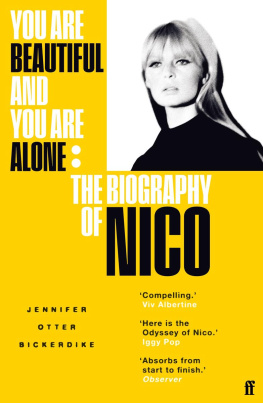

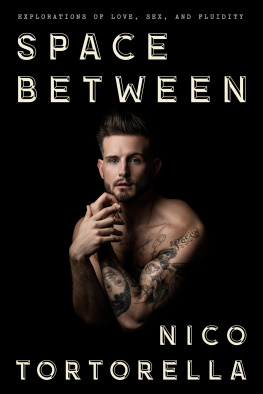

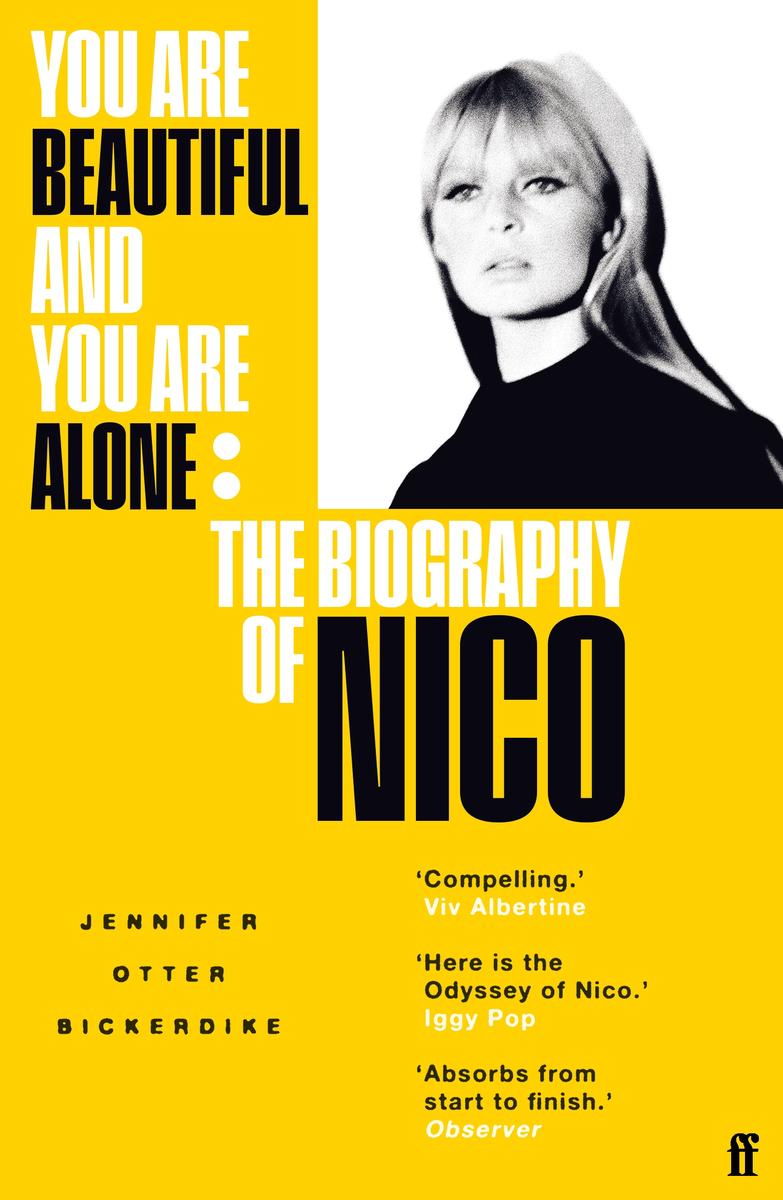

What I have in common with Nico is the understanding of her furious frustration at not being recognized.

Marianne Faithfull

I was very, very late discovering Nico. One night, I was out with a friend, discussing our personal female rock heroines. I was both surprised and mortified to find that compared to all of the men in music that we loved, the list of women we could come up with was woefully short. Upon getting home, I did a bit of research to see what fantastic females I had forgotten. I came to Nico. She was in the Velvet Underground for that one crucial record; she had that Chelsea Girl album. But what else? I started to look a bit deeper into her life, my years as a PhD student researching pop culture making it natural for me to crawl down the rabbit hole of this enigmas history. At the beginning, I assumed I would unearth the usual story of rock highs, lows, a comeback and an eventual career playing at county fairs and heritage gigs. What I found instead was a life and a myth that became more surreal the further I dug.

Almost every aspect of Nicos life has been haphazardly recorded, if accurately chronicled at all. The repetition of the same anecdotes has somehow mutated random incidents specific to contextualized moments into grand brushstrokes of over arching truisms. The more I tried to figure out who the real Nico was, the greater the rupture became between the oft-repeated myths, the few documented facts and the personal memories of those who knew her best. Any new crumb of information was hard-won and precious, often the result of weeks spent digging in dusty and long-forgotten archives, months of scanning through old microfiche, and countless emails and phone calls, all in the hope of discovering something not previously known. More than a hundred new interviews were carried out in pursuit of establishing a more well-rounded understanding of the icon. What emerged was a didactic example of apathetic misogyny and stereotyping on the part of written history, a narrative that lazily rests upon the familiar, salacious and utterly predictable realms of sex, drugs and rocknroll excess, without acknowledgement of the unique and often unnerving life circumstances of the singer. At first it seemed too simplistic to blame the quagmire separating the two versions of Nico on nationality, misogyny and cultural expectations. Yet the more I learned about her, the more obvious this explanation became. There were very few women writing about and documenting rock music at the time, and even fewer brave enough to break societal expectations of what or how a female could be as an artist. This meant an often one-sided narrative was created and perpetuated about Nico, as there were no other female voices to challenge it or offer a counterpoint.

From her name to the diametrically opposed personas she inhabited over the span of her life, it is hard to discern who the real Nico was. It has not been an easy task to tease apart fiction and folklore from often long-forgotten fact. The majority of Nicos life was spent as a solo artist, with little formal documentation. There are also numerous conflicting claims about her, ranging from when she was born (1938? 1942?) to her political ideas (was she a Nazi? Or a Jew herself?). And though hardship and horror are common threads throughout Nicos story, so are moments of humanity and humour, such as the singers love for making brown rice and vegetarian soup (Always have an onion, she once told a friend), or her attempt at seducing a potential partner with a box of Cadburys Roses chocolates.

Several aspects of Nicos life are certain. Born in Cologne to parents of Spanish and Yugoslavian descent, Christa Pffgen carried with her the guilt and unease of being brought into the world and raised in Germany during World War II. Her father, Willi, was drafted into the Wehrmacht; she never saw him again. This would haunt her for the rest of her life. Nico was a persona, created one day in 1956, when fashion photographer Herbert Tobias suggested to the then teenage aspiring German model that she should change her name, causing a protective shield between the fragile survivor and the public character to be forged. The nom de guerre paid off, as Nico began landing modelling jobs for fashion hard-hitters across Europe, including Vogue and Elle. She moved from modelling to acting, most notably scoring an unforgettable cameo in Federico Fellinis 1960 art-house masterpiece La Dolce Vita. After being encouraged by a lover to try her hand at singing, Nico eventually found herself at artist Andy Warhols notorious Factory in New York, a hub for outsiders, creatives and non-conformists. Warhol and his collaborator Paul Morrissey had just decided to work with a then unknown band, the Velvet Underground. The duo agreed to fund the fledgling group, if they let Nico front them as the visual element.

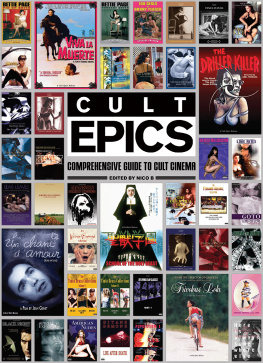

While the Warhol days boast ample images, anecdotes and interviews, the later, perhaps more authentic version of Nico the two decades spent touring the globe as a solo artist has been virtually lost and rarely discussed. This has created a vacuum, allowing Nicos legacy and impact as a cultural icon to be often solely defined by her supposed superficiality, which sees her cast as a racist junkie who slept with a myriad of famous men. Her fellow Velvets Lou Reed and John Cale are consistently hailed as American masters, poets and legends, their creativity and talent the main focus for the dispersion of such accolades. When physical appearance, sexual exploits, political leanings and substance-abuse issues are woven into the overall tapestry of their stories, it is often as part of the expected journey for any real artist. Yet Nicos genius contributions to rock culture are often overlooked, her value to contemporary music trivialized to her simply being a beautiful mannequin for the Velvet Underground.

Nicos five albums post-Girl many of which are now considered undervalued treasures by critics showcase a polluted, heroin-addicted, henna-haired singer with a repertoire of songs that are focused on the morbid and the dark. It is the demise of her legendary appearance, not the music, that is often remembered. Though her other-worldly beauty granted Nico access and opportunity, she also saw it as a hugely problematic attribute that prevented her from being taken as a serious artist not just a female performer with a pretty face. Her apparent need to destroy this valued asset was not lost on those around her. As the years went by, the few press write-ups Nico received often hastened to note that, along with her deteriorating fan base, increasing age and fifteen-year opiate addiction, she had lost her fresh-faced youth. Even her former benefactor Warhol called her old and fat in 1980. People rarely saw or acknowledged the woman who could speak seven different languages fluently, read classic literature voraciously and finish the New York Times crossword puzzle in near record time.

Nicos continued determination to make music, seemingly against all odds whether fuelled by artistic ambition or a need to fund her drug abuse along with the empty concert halls, abusive fans and the uncertain and often perilous reality of being an ageing artist and addict, have often been cast aside in our cultural memory. This makes her story a chilling modern narrative on the fetishism of beauty, ageism and the romanticization of death, at the cost of a talented, lonely and eccentric musicians life. As a solo artist, Nico created mesmerizing and thoroughly unique projects that inspired a generation of artists, including Henry Rollins, Morrissey and Marc Almond. She was a true bohemian who deserves proper recognition for her brave, ballsy, often weird and always deeply personal albums, which created a template for the modern genres of rock, punk and goth.