Authors Note

Unless otherwise attributed, all quotations and dialogue in this book have been taken directly from the writings of Henry Stanley. A list of his works is given in the bibliography.

Bibliography

Anstruther, Ian. Dr. Livingstone, I Presume? New York: E. P. Dutton, 1956.

Bent, Laura. Stanley, Invincible Explorer. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1955.

Feather, A. G. Stanleys Story, or Through the Wilds of Africa. John E. Potter & Co., 1890. Reprint. Chicago: Afro-American Press, 1969.

Farwell, Byron. The Man Who Presumed. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1957.

Davidson, Basil. Africa in History. New York: Macmillan, 1968.

Jeal, Tim. Livingstone. New York: G. P. Putnams Sons, 1973.

July, Robert W. A History of the African People. New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1970.

Keltite, J. Scott, ed. The Story of Emins Rescue As Told in Stanleys Letters. New York: Harper, 1890. Reprint. New York: Negro University Press, 1969.

Moorehead, Alan. The Blue Nile. New York: Harper and Row, 1962.

. The White Nile. New York: Harper and Row, 1960.

Stanley, Henry M. The Congo and the Founding of the Free State. 2 vols. New York: Harper, 1885.

. How I Found Livingstone. New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1872. Reprint. New York: Arno Press, 1970.

. In Darkest Africa. 2 vols. New York: Scribners, 1890.

. My Early Travels and Adventures in America. London: S. Low, Marston, 1895. Reprint. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

. My Kalulu. New York: Scribners, 1874.

. Through the Dark Continent. 2 vols. New York: Harper, 1878.

Stanley, Henry M., and Stanley, Dorothy. The Autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1909.

Seitz, Don C. The James Gordon Bennetts. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1928.

CHAPTER 1 The Mountains of the Moon

N o unexplored region in our times, neither the heights of the Himalayas, the Antarctic wastes, nor even the hidden side of the moon, has excited quite the same fascination as the mystery of the sources of the Nile. For two thousand years at least the problem was debated and remained unsolved.... By the middle of the nineteenth century ... this matter had become ... the greatest geographical secret after the discovery of America. So begins Alan Mooreheads classic The White Nile.

It is not hard to understand why the unknown source of the Nile fascinated people. The Nile is the basis of life in Egypt, home of one of the oldest, most powerful, and most exotic of all ancient civilizations. Without the Nile there could have been no Pyramids, no Sphinx, no civilization at all in Egypt, for it almost never rains there, and agriculture depends entirely on water drawn from the river and particularly on the annual flood that renews both the moisture and the soil of the Nile Delta. If the flood failed for a single year, Egypt would perish. But it has never failed, not once in thousands of years of recorded history. And the flood rises during the driest and hottest time of the year.

Where does all that water come from?

The Nile flows north from the center of Africa through more than a thousand miles of hot, rainless desert. The source of the Nile clearly lay somewhere in the middle of the African continent, but all attempts to find the place where the great river began proved to be incredibly difficult. Going upriver, against the current, was hard enough, particularly in the days before steam power. There was the heat of the desert and the great rapids, or cataracts, of the Nile to be passed. And if these difficulties could be overcome, there was the impassable barrier of the Sudd.

In the southern part of the Sudan the air grows more humid, and the banks of the Nile are green year round. Soon the traveler finds that the river has merged with a huge swamp that is the Sudd. There is no clear channel through this vast region of weed-choked muddy water. The swamp is the home for the hippopotamus, the crocodile, and clouds of disease-bearing mosquitoes. Many travelers had tried to trace the course of the river through the Suddnone had succeeded. The great swamp was impenetrable.

Another approach to finding the source of the Nile was to march inland from either the east or west coast of Africa right to the heart of the continent. But this required a march of hundreds of miles through hostile and completely unknown territory, for up until the middle of the last century the center of Africa was just a big blank marked unexplored on the worlds maps. How could any explorer be sure that he had really found the source of the Nile? Aside from the enormous difficulties of African exploration, there were endless bitter disputes over the significance of different discoveries.

Yet the source of the Nile was not truly unknown; someone had once known the source, but that knowledge had been lost. There was a widely repeated story that in the first century A.D. a Greek merchant named Diogenes landed on the coast of Africa and, according to his own account, travelled inland for a 25-days journey and arrived in the vicinity of two great lakes and the snowy range of mountains whence the Nile draws its twin sources. In the second century A.D., the great Egyptian geographer Ptolemy drew a famous map of Africa that showed the Nile originating in two lakes that were in turn watered from a high range of mountains, the Lunae Montes, the Mountains of the Moon.

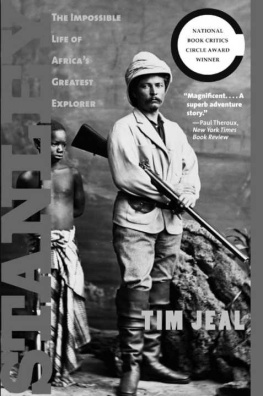

Vague reports of snow-capped mountains in Central Africa had filtered out of the unknown interior for a long time. But most nineteenth-century geographers refused to believe such reports, because the existence of un-melted snow so close to the equator seemed ridiculous. Yet the snow-capped Mountains of the Moon that are the ultimate source of the Nile do exist. The man who first brought credible reports of the mountains to the outside world was the greatest of all African explorers, Henry Morton Stanley.

Like other African explorers of the nineteenth century, Stanley too had taken part in the great quest for the source of the Nile. Yet when he found the Mountains of the Moon he was not really looking for them. It was 1889, and Stanley was on his last, strangest, and most terrifying African journey. He had faced extreme hardships before, but nothing matched the horrors of the Ituri Forest. There were starvation, disease, ghastly accidents, and almost constant attack from hidden Pygmy enemies. His men were dropping around Stanley at a frightful rate. Those who didnt actually die were usually too starved and sick to move. Stanley himself was often driven half mad with pain or was delirious with fever. Yet somehow he persevered and broke out of the forest. On April 20, 1889, the advance party of Stanleys expedition reported seeing a white mountain. A month later Stanley himelf saw the mountain, or more accurately a whole range of snow-capped mountains, on the equator in the heart of tropical Africa! It was then that Stanley realized that he had found the fabled Mountains of the Moon, the ultimate source of the Nile.

Other travelers had passed close enough to the Mountains of the Moon, or Ruwenzori, as they were called, to see them. But somehow mists or clouds had always obscured the mountains. The mists cleared for Stanley. He had always felt that his life had been guided by some sort of special Providencethis was just another example of it.

Stanley can be excused for believing in special Providence. His own life was so improbable that it is hard to believe. It could have been dreamed up by a collaboration of Charles Dickens and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Stanley became one of the most famous men of his day. Everyone in Europe and America knew of his exploits. His African nickname Bula Mataribreaker of rockswas known from one end of Africa to the other. There was a mountain, a lake, even a city named after him.