Acknowledgments

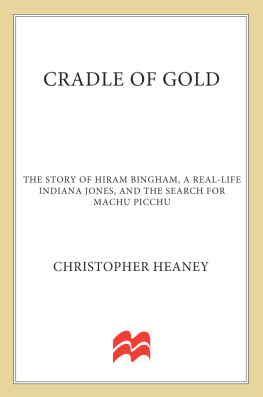

I would like to thank Judith Schiff and the staff of the Manuscripts and Archives Room at Yales Sterling Library for all the help they gave me in consulting the Bingham family papers. I would also like to thank Dr. Leopold Pospisil, director of the Division of Anthropology at Yale, who gave me permission to examine the extensive photograph collection of the Yale Peruvian expedition. Special thanks are due to David Kiphuth of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, who actually guided me into the vault where the collection is stored. I am grateful to the Peabody Museum for permission to reproduce the pictures from the expedition that appear in this book.

Bibliography

Bingham, Hiram, Sr. A Residence of Twenty One Years in The Sandwich Islands. Hartford, Conn.: Hezekiah Huntington, 1849.

Bingham, Hiram, III. Across South America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911.

. The Discovery of Machu Picchu. New York: Harper, 1913.

. Elihu Yale: The American Nabob of Queen Square. 2nd ed. Archon Books, 1968.

. An Explorer in the Air Service. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1920.

. Inca Land: Explorations in the Highlands of Peru. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1922.

. Journal of an Exploration Across Venezuela and Colombia, 19067. New Haven: Yale Publication Association, 1909.

. Lost City of the Incas: The Story of Machu Picchu. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948.

De Camp, L. Sprague, and De Camp, Catherine C. Ancient Ruins and Archaeology. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1964.

Deuel, Leo. Conquistadors Without Swords. New York: St. Martins, 1967.

Hemming, John. The Conquest of the Incas. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970.

Miller, Char. Fathers and Sons: The Bingham Family and the American Mission. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982.

CHAPTER 1

An Unbelievable Dream

O n the morning of July 24, 1911, Hiram Bingham was about to make the greatest discovery of his lifein fact, it would be the greatest archaeological discovery that has ever been made in the Americas. But as the day dawned in a cold drizzle, there were no signs or portents of what was to come in just a few hours.

The weather was so miserable that Melchor Arteaga, the farmer who had first told the members of the expedition about Inca ruins in the mountains, didnt even want to leave his hut. It was only after Bingham offered him a Peruvian golden sol, three times the usual guides fee, that the farmer reluctantly agreed to go.

Other members of the Yale expedition had no faith in Arteagas story, especially on so wet and chilly a morning. When the farmer had been asked where the ruins were, he just pointed straight up. They had heard similar rumors of ruins and had scrambled up and down mountains only to be disappointed. Harry Foote, the naturalist, decided that there were more butterflies near the river and that he was going to stay and collect them. Dr. William Erving, the surgeon, said he had to wash and mend his clothes. Besides, it was Bingham who had really dragged all of them into the Peruvian jungle to look for lost cities of gold, so finding the ruins was really his responsibility. He was the one who was supposed to follow through on every rumor, no matter how unpromising. And this rumor was an unpromising one indeed, for as far as they knew no one else had ever reported Inca ruins in this area of the Urubamba River.

So at about ten oclock, Bingham, accompanied by Arteaga and the Peruvian officer Sergeant Carrasco, started off on the forested trail that followed the course of the Urubamba. Bingham saw a recently killed snake along the side of the road. It was yellowish in color and had a triangular pointed head. He asked Carrasco what sort of snake it was.

Viper, replied the sergeant. Bingham knew that meant fer-de-lance, the lance-headed, or yellow, viper, the deadliest snake in the world and an aggressive killer that was known to actually spring through the air in pursuit of its victims. Carrasco casually mentioned that these vipers were quite common in the area. Bingham shuddered and walked more quickly.

The trail led through a spectacular landscape that Bingham would write about: Great snow peaks loom[ed] above the clouds more than two miles overhead and gigantic precipices of many-colored granite [rose] sheer thousands of feet above the foaming, glistening, roaring rapids. On the peaks above, glaciers shimmered through the clouds. Below the peaks was dense tropical jungle. Along the road grew gigantic tree ferns, and orchids bloomed on their trunks and in their spreading branches. It was a land of unsurpassed beauty and great danger.

After about three-quarters of an hour of walking, Arteaga left the road and plunged through the jungle to the riverbank. He gestured somewhat uncertainly to a bridge that crossed the turbulent Urubamba at its narrowest point. The bridge was really a series of logs that spanned the gaps between boulders that stuck up out of the rapids. In his travels through the mountains of South America, Bingham had seen many primitive and rickety bridges. This was surely the worst. As he noted later, The bridge was made of half a dozen very slender logs, some of which were not long enough to span the distance between the boulders but had been spliced and fashioned together with vines!

The river boiled up just a few feet beneath the bridge, and the logs were slippery and moss covered. Bingham knew that with one misstep he would plunge to an instant death in the icy rapids. Arteaga and the sergeant took off their shoes and crept carefully across, gripping the logs with their toes. Bingham, who was not used to gripping anything with his toes, adopted a different method. He got down on all fours and crawled across, a few inches at a time. Though he was a college teacher of history, this was no place to try to look dignified. As soon as he got across, instead of being relieved, he began to worry about how he was going to get back. The bridge was already under siege by the rapids. If it rained the frail logs would be washed away entirely.

Once again the trio plunged into the jungle, and in a few minutes they reached the base of a mountain, which seemed to Bingham, at least, to rise straight up. For the next hour and a half they climbed and clawed their way up several thousand feet. For a good part of the distance we went on all fours, sometimes holding on by our fingernails.

The sergeant was grateful that his heavy boots were snakebite proof. But Arteaga worried and continued to talk loudly about snakes. After a while, Bingham began to wonder if a mere snakebite would not come as a welcome relief. Both the heat and the humidity were tremendous, and as Bingham discovered, he was in no shape for such a climb. He struggled for breath and swore that every foot of the climb would be his last. Worse still, there was no sign of ruins. There were signs that the area had once been inhabited or used as a trail. In one spot, the climbers found a notched tree trunk that served as a primitive ladder. But such signs were recent in origin. The whole venture might be a complete fiasco.

By noon Bingham was convinced that he was not going to be able to go any farther, that if the Lost City of the Incas itself lay at the top of the mountain, he would not have the strength or will to reach it. And then, amazingly, the climbers came upon a grass-covered hut inhabited by two very good-natured Indians who offered them gourds filled with cool, delicious water. To the exhausted Bingham the sight of the two smiling men holding out the overflowing gourds was like a vision, a dream. It was the first of a series of dreamlike experiences he was to have that day.

Over a lunch of boiled sweet potatoes, the two Indian farmers, Richarte and Alvarez, explained that they were able to grow a variety of cropspotatoes, beans, peppers, and tomatoeson terraces that had been built into the mountainside. Why had they chosen to live in such a remote spot? The two men laughed and said that up here they were safe from the tax collectors and from army men looking for volunteers. They went into the valley about once a month along the path that Bingham and his companions had just climbed or, during the rainy season when the bridge was washed out, along a path that was even steeper. Bingham found it difficult to imagine what that path might be like.