Preface

As a biographer I have been faced with what is a rare, if not unique problem. For the last five years of his life I was Robert Shaws agent and for three years before that, worked for his then agent as an assistant. In preparing this book, therefore, I was faced with a dilemma. I first met Robert Shaw in Richard Hattons offices in Curzon Street after his return from appearing in the musical of Elmer Gantry on Broadway in 1970. Properly therefore, in the telling of the story, an I should enter the narrative at the half-way point in the book. As this, to my mind, would have been intrusive in the story of someone elses life, there seemed to be only one solution and that was to treat John French like any of the other characters who appear in the book, and use the third person. The introduction of an I would have changed biography into a sort of hybrid autobiography. Hopefully this device will not appear too arch to the reader.

Immediately after Shaws death, some of the more sensational aspects of this book might well have appealed to the tabloid press. His sudden death was, after all, a good story. I felt, however, that then was not the time to publish. Not only would the more prurient events be taken out of context but such treatment would do nothing to explain and characterise a quite extraordinary man. The main purpose of this book, for me at least, is to explain to those who knew Robert Shaw what had gone wrong in his life and to try, for those who didnt, to bring alive a man whose vivacity, charisma and sheer personality were unique, while documenting how this personality and its undue weight of talent came to such an untimely and unfulfilled end.

April 1993.

Foreword by Richard Dreyfuss

Robert was the largest personality I have ever encountered.

He told the best stories. Like watching Brando do Antony in the 50s with other stars-to-be from the 60s, and all turning to one another silently with a look that said, contrary to all the notices Brando had had flung at him, Hes genius.

One afternoon in the sleeping quarters of the Orca, the workboat that was our at sea rest area/equipment holder/kitchen, as we were waiting through another interminable amount of time for a sailboat to get out of our shot which could sometimes take an hour, Robert, who was in another bunk, jumped up and said I know, Ill play the ghost to your Hamlet if you play the Fool to my Lear!

You got it! I answered, but not for ten years.

Why? he asked, and I said Because youd blow me out of the water any time sooner, and you know it.

And he laughed, and laughed, and agreed.

One thing Im sure of is that hed lived, wed have done it together long before this.

He was Big, Brilliant, Boisterous, a work of Art unto himself, like a cross between Beethovens thunder and Lokis jokes. He terrified me and I loved him. I was his Gunga Din, sometimes to be flayed, sometimes singled out for praise.

He was the most competitive human being ever. Richard Zanuck held up shooting all day once because Robert kept beating Dick at ping pong, and Richard was the producer who let the cost of the days shoot slide away rather than let Robert beat him.

The day he decided to shoot the story of the SS Indianapolis REALLY drunk, became the longest day of my life, because he couldnt do it; I was in the shot with him, listening. Everyone felt sorry for him; we were all aware that he was aware which made him drink more; finally Steven Spielberg simply waited for Robert to get to the end of a sentence, and called Great! Wrap. That was ten long hours.

That night at 3am, he called Steven Spielberg and said How badly did I humiliate myself?

Not fatally Steven replied, and the next day he did the entire monologue in one take.

Brilliantly.

One day I saw him crossing his name off a piece of paper and asked him what it was about. He explained that the play The Man in the Glass Booth that he had written had been turned into a film, and the meaning of the play had been distorted, so he was taking his name off it.

I asked what it was about, and two minutes later we were sitting in the hold of the Orca and he was explaining it was the story of a man who was either an Eichmann that the Israelis had kidnapped and brought home for trial, or he was an insane Jew pretending to be a Nazi. I think he read all of the play to me, and then he read all of the finale, a long and terrifying speech that began Let me speak to you of love; let me speak to you of the Fhrer. Then it concluded with Robert saying his characters final lines right into my eyes: Children of Israel Children of Israel, if he had chosen You, you also would have followed where he led.

I had been entranced by all of him, the intellect, the courage of what we now call the political incorrectness; the voice, (my God, give me that voice), the art of his prose, and I awoke from that only to realize that the entire crew had been filling the portholes, listening, including Steven, as hypnotized as I. Maybe three hours, thousands of dollars; worth every penny.

He was astonishing in his acting: I thought his Claudius the best and told him and he was childlike with pleasure. No matter that this book says he wasted himself, so did all the others I worshipped that Robert thought were ahead of him: Burton, OToole, Harris

I complimented him on his Henry VIII in A Man For All Seasons for which he had won an Oscar nomination; he cackled like Quint and then he told me that hed played the part in one day.

In the morning, first, the landing of the king, off the river boat; then the leaving of the king onto the riverboat; then dancing with Vanessa Redgrave; and then the long and enormously dramatic scene with Paul Scofield. Take a look. One day. Thats what he said.

On the day I heard hed died I drove to Stevens house, and found him wordlessly playing the piano; I think I might have tried to speak but he was only sitting and playing, head down. For a long time. I left and drove my Mercedes aimlessly.

I was cheated out of playing his Fool. I miss him, more than even then I knew, because recently I was on an Irish talk show and was introduced to his grand-daughter, who had never met him, and I burst into uncontrollable tears; I think because a part of me still grieves at what I could have learned, and how spectacular a companion he was.

Imperious Caesar dead and turned to clay...

January, 2015.

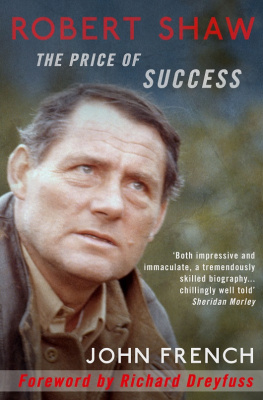

John French

Robert Shaw

THE PRICE OF SUCCESS

Robert Shaw is most celebrated today as the Oscar-nominated star in movies like From Russia with Love, A Man For All Seasons, The Sting and most memorably of all as Quint in the record-breaking Jaws.

His breakthrough came when Hollywood was experiencing something of a British Invasion. Sean Connery, Peter OToole, Vanessa Redgrave and Richard Burton were among the new stars. But Shaw was arguably more talented than any, a figure of extraordinary and wide-ranging promise. More than just a mesmerising actor on stage and screen, he was also a gifted writer. He wrote no less than six published novels (winning the Hawthornden Prize), while his plays include the acclaimed Man in The Glass Booth.

The flipside to Shaws diverse abilities was his well-earned reputation as a hellraiser. A fiercely competitive man in all areas of his life, whether playing table tennis or drinking whisky, he emptied mini-bars, crashed Aston Martins, fathered nine children by three different women, made (and spent) a fortune, and set fire to Orson Welles house. He died at 51, having driven himself too hard, too fast, but unable to get over his fathers suicide when Shaw was just 11.

John French, Shaws biographer, knew him well, professionally and personally.