LADY GREGORY

JUDITH HILL is an architectural historian and writer. Her previous books include The Building of Limerick(1991), Irish Public Sculpture: A History(1998), and In Search of Islands A Life of Conor OBrien(2009). She has taught Irish cultural history, written for the Irish Arts Review, The Irish Times and Times Literary Supplement, and featured on RT television and radio. She lives in Limerick.

For Kathleen and Peter

LADY GREGORY

AN IRISH LIFE

JUDITH HILL

www.collinspress.ie

Twitter

Facebook

FIRST PUBLISHED IN IRELAND IN 2011 BY

The Collins Press

West Link Park

Doughcloyne

Wilton

Cork

First published in hardback by Sutton Publishing Limited in 2005

Judith Hill 2005, 2011

Judith Hill has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved.

The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except

as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be

reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted

in any form or by any means, adapted, rented or lent without the

written permission of the copyright owners. Applications for

permissions should be addressed to the publisher.

EPUB eBook ISBN: 9781848899353

mobi eBook ISBN: 9781848899360

Paperback ISBN-13: 9781848891104

Cover design by Burns Design

Typesetting by Red Barn Publishing

Typeset in Sabon

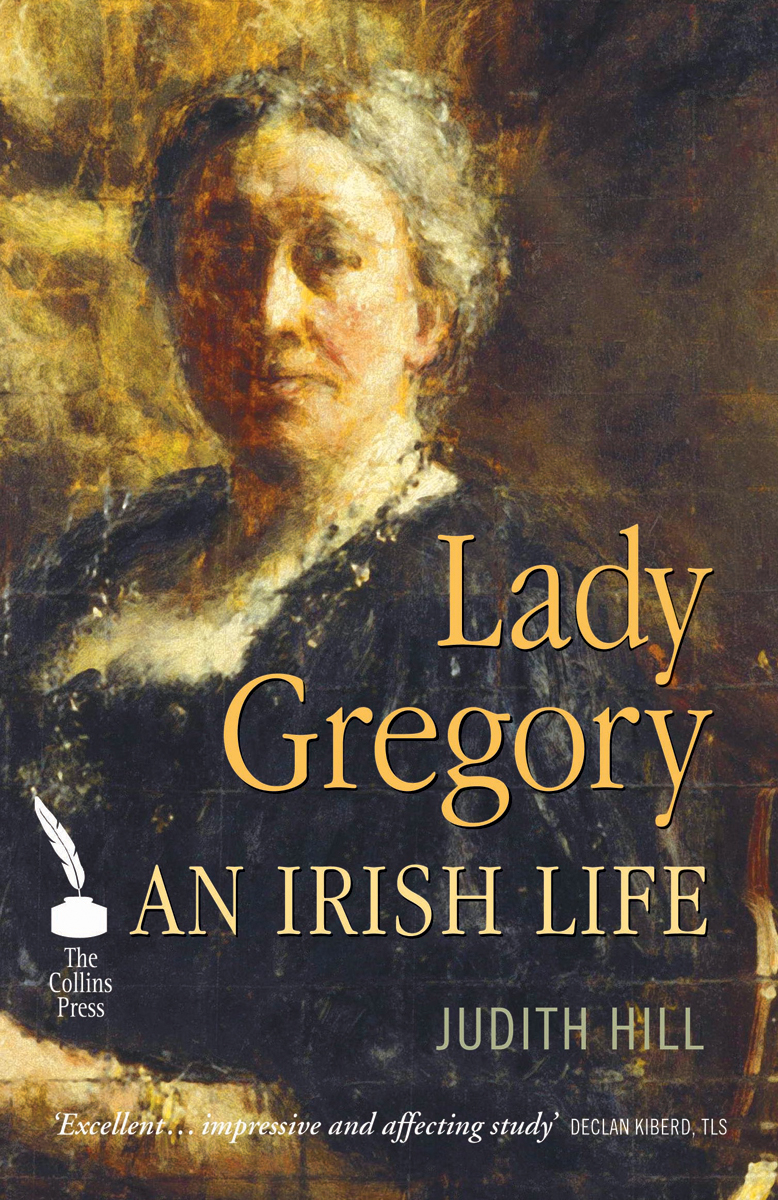

Cover photograph: Portrait of Augusta, Lady Gregory by Antonio

Mancini (1908). Collection: Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane.

Contents

Acknowledgements

M y greatest debt is to the libraries and their unfailingly helpful staff: Mary Immaculate Library, Limerick; University of Limerick Library; Noel Kissane and Elizabeth Kirwan, Department of Manuscripts and Colette OFlaherty, National Library of Ireland; Trinity College Library; Mary Boran, The Special Collections and Kieran Hoare, archivist, National University of Ireland, Galway; Catherine Farragher and Mary Quilter, Galway County Libraries; The Kiltartan Museum; Raymond Refauss, The Representative Church Body Library, Dublin; Mary ODoherty, The Mercer Library, Dublin; Richard Mills, The Royal College of Physicians, Dublin; Mairead Delaney, The Abbey Archive; Kathy Shoemaker and Stephen Enniss, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University, Atlanta; Rodney Phillips and Isaac Gewirtz, The Berg Collection, New York Public Library; The British Library.

Entering a field of great scholarship, I am indebted to the work of many scholars, including Roy Foster, Adrian Frazier, Nicholas Grene, John Kelly, David Krause, Dan Laurence, Lucy McDiarmid, Daniel Murphy, Christopher Murray, James Pethica, Ann Saddlemyer.

Several people agreed to be interviewed and shared their memories of Lady Gregory with me: the late Martin Hehir, the late Catherine Kennedy, Anne de Winton.

I received great encouragement and help from a number of people who gave me specialist advice: Brian Coates, Mary Coll, Patricia Conboy, Maura Cronin, Sheila Deegan, Sister Mary de Lourdes Fahy, Terry Devlin, Roy Foster, Caroline Hill, Kathleen Hill, Madeleine Humphreys, Declan Kiberd, John Logan, Patricia Lysaght, Maurice McGuire, Philip McEvansoneya, Deirdre McMahon, G.D. Mulroney, Jane Murray Brown, Mire N Neachtain, Sheila ODonnellan, Lionel Pilkinton, Pat Punch, John Quinn, Veronica Rowe, Colin Smythe, Monica Spencer, Lois Tobin.

The Royal Irish Academy very generously awarded me two Eoin OMahony bursaries, which allowed me to travel to New York.

I am very grateful to my agent, Sara Menguc, who has been encouraging at the worst times; to my excellent editor at Sutton [publishers of the hardback edition], Jaqueline Mitchell; to my editors at The Collins Press who allowed me to make some minor adjustments, my understanding children, Lily and Helena; and to Mark Davies, who is a rock.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the Berg Collection of English and American Literature, the New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations for permission to quote from Lady Gregory and Edward Martyn correspondence in their collection; the Foster-Murphy Collection Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations for permission to quote from material in their possession; Special Collections and Archives, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University, for permission to quote from material in the Gregory Family Papers; National Library of Ireland for permission to quote from Lady Gregory corres pondence; A.P. Watt Ltd on behalf of Michael B. Yeats for permission to quote from the published prose and poetry of W.B. Yeats; the Society of Authors on behalf of the Bernard Shaw Estate for permission to quote from George Bernard Shaws letters; the Catholic University of America Press, Washington DC for permission to quote from the letters of Sen OCasey; Pan Macmillan UK for permission to quote from Sen OCaseys autobiography.

Preface

L ady Gregory lived a full life, very different from the one mapped out for the daughter of a Galway landowner, born in mid-nineteenth-century Ireland. She founded the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, supplied it with a steady stream of plays and directed it through controversy and war. She was a close friend, patron of, and artistic collaborator with the poet W.B. Yeats. She was a pioneering folklorist. She made Coole Park, County Galway, a home of the Irish Literary Revival, and was an influential commentator on Irish culture. She supported her nephew, the art collector Hugh Lane, in his desire to establish a modern art gallery in Dublin, and fought tirelessly for his pictures to be returned to Ireland from Britain. She loved her husband, her son, Robert, her three grandchildren, her numerous friends, and she had two lovers. She suffered too; most heartbreakingly when Robert and Hugh were killed in the First World War.

It was not, as might be anticipated, a straightforward life. There were many intriguing contradictions. She gradually gained an empathy with those from whom she was separ ated by birth, education, culture, habit, dress, manner of speaking and family allegiance, to become a nationalist. Yet she remained a landowner, collecting twice-yearly rents, grooming her son to take up his inheritance. She was ambitious to succeed as a writer, and could be forceful when trying to get her own way in the Abbey. But she believed that women should put men first, or at least be seen to, and so she concealed some of her successes and made her presence felt indirectly. She made no public statements about the role of women in society, and lived her life as though there was no need for change. Yet in several of her plays she demonstrated an interest in questioning traditional female roles, and she explored the lives of strong women. There were hidden contradictions, too. She seemed the epitome of an emotionally restrained person; she had married pragmatically, and after her husbands death her forty years of widows black proclaimed a lack of interest in re-marriage. Yet she had two passionate affairs, and her letters and diaries reveal the depth of her love for her son and grandchildren. She was extremely secretive about her private life. However, several of her plays contain surprisingly significant auto biographical seeds. She is a fascinating character, at once a product of her class and time, and a rebel against circumstance.