ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

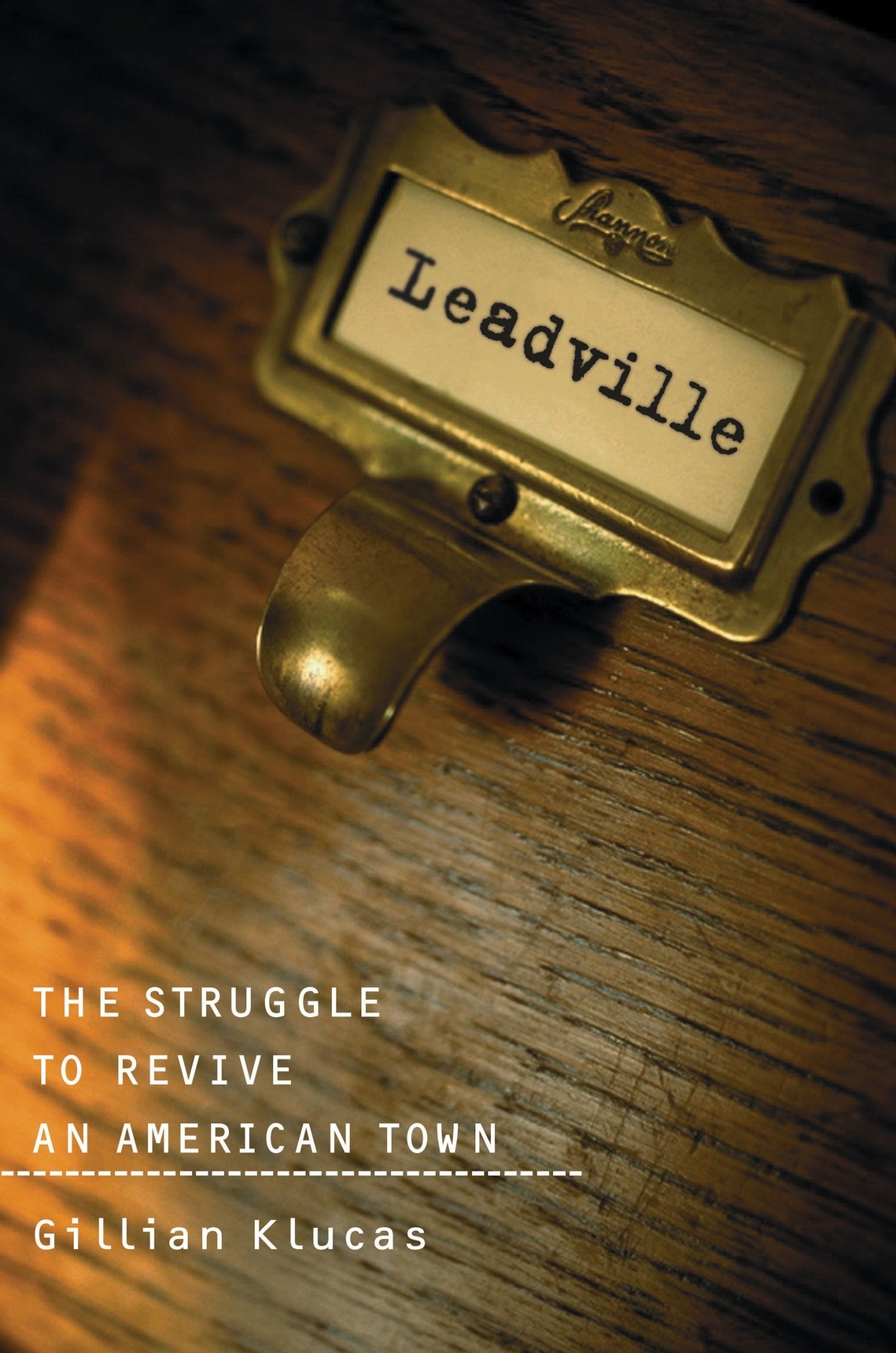

This book could not have been written without the assistance of many people. My heartfelt thanks, first, to the citizens of Leadville who welcomed me and shared their stories. Leadvilles friendliness and generosity made my stay a happy time. I would especially like to thank Bernard and Carol Smith, Jim and Corinne Martin, and Mike Holmes for the many hours they spent helping me untangle the events of the past twenty years, sometimes while driving me around the mining district, particularly during the early days of my journey.

My deepest thanks to the many people who appear in this book for giving so generously of their time and for their patience. Many others whose names do not appear also gave generously of their time, sharing their experiences, helping me with research, or welcoming me in Leadville. In particular, I would like to thank Jerry Andrew, William Atkinson Jr., Tom Cherrier, Laura Coppock, James Fell Jr., Kathleen Fitzsimmons, Larry Frank, Tom Holford, Karmen King, Christine Londos, Ellen Mangione, Nancy Manly, Jody Martinez, Sam McGeorge, Brad Littlepage, Amy Morrison, Peter Moller, Ken Olsen, Bryce Romig, Donald Seppi, Bill Scherer, Duane Smith, Steve Voynick, the librarians at the Lake County Public Library, and the ladies behind the counter at the Cloud City Coffeehouse in the Tabor Grand building where I spent many hours working and relaxing.

I would also like to thank the Colorado Historical Society, which started me on this journey many years ago. In particular, my thanks go to Patrick Fraker, Aaron and Karen Mandel, David Wetzel, and Carol Whitley for their support, assistance, and friendship.

I am grateful for the invaluable financial support I received early in this project from a Preservation magazine fellowship.

I owe a great debt to Jonathan Cobb, my editor at Island Press, who believed in the value of telling this story and in my ability to tell it, and whose diligence and skillful editing helped make this a much better book.

Most importantly, I would like to thank my parents, Robert and Carol Klucas, who have supported me in so many different ways over the years. This book could not have been written without their love and encouragement.

Epilogue

In the opening years of the twenty-first century, signs of change in Leadville are everywhere. It can be heard not just in the Spanish spoken in town but in the public debates taking place in local government meetings as Leadvilles newcomers demand better schools, more businesses, and a cleaner environment. The mentality is changing, said one longtime resident. It isnt even subtle. A lot of people are seeing the writing on the wall. Many of these newcomers bring with them a new energy, a willingness to work together, and the know-how to get things done.

The changes can be seen on Harrison Avenue. Outside money is slowly sprucing up Leadvilles main street. After a corner of the Tabor Grand, the pigeon coop once eyed for a parking lot, collapsed in a rainstorm the day after its new owner purchased it in 1991, he worked with the federal Department of Urban Housing and Development to create low-income apartments. Some, including the newspaper editor of the time, thought it was beneath the towns dignity, but several million dollars later the Tabor Grand Hotel is the pride of Harrison Avenue, housing a block of shops, including a real estate office, beauty salon, and one of Leadvilles two coffee shops selling lattes and cappuccinos. Some buildings remain boarded up and decaying, but the Quincy Block, the turreted Bank Building, the gothic Old Church, and others are in various stages of renovation. A few steps off Harrison on 6th Street, the decaying Italianate-style house once owned by the Guggenheims was also recently restored as a private residence. Live bands play in Leadvilles other coffee shop that doubles as a low-key bar. The Silver Dollar with its blended Irish and Wild West themes is still there, as is the Golden Burro, a perpetual For Sale sign in its window. Leadville has bed-and-breakfasts, a few upscale gift shops, and many more rubber tomahawk shops reminiscent of the 1950s. In the summers, wooden planters of columbines and pansies line Harrison Avenue. Brooklyn Heights, a subdivision featuring New Victorian Homes, is going up south of town.

In 2003, when Mayor Chet Gaede decided not to run for reelection, the town faced an important decision. The two frontrunners to replace him were Lisa Dowdney, the former libertarian of the keep Chet in line philosophy, and Bud Elliott, a motel owner on the towns tourism task force. Lisa had come to Leadville in the 1970s and had the distinction of being one of few women who had ever worked underground at Climax. Now, she was unemployed. Bud had once worked as a nurse on the psych ward in Kansas City. He came to Leadville in 1993 with a young son after his wife died. As a city council member, Bud was the court jester. He looked benevolent, round, and soft as he tipped back comfortably in his chair at the end of the table watching the edgy mayor, unyielding Carol, and the others go at it. His bemused smile suggested that he thought this was better entertainment than reality TV. Every once in a while, Bud righted his chair and zipped in a one-liner. During one argument over spending money to fix the roads, for example, Bud asked the dissenting libertarian if cars ruined by the resulting potholes would be considered a taking by the city, poking fun at the libertarian partys aversion to governmental seizing of property. Another time, a county commissioner asked for volunteers to help water a grove of newly planted pine trees. Itll be a lovely day, he said. A chance to walk your dogs. How many dogs are you going to need? Bud quipped.

Bud campaigned on code enforcement, Lisa on a less-threatening government. The town was divided. But as the two made their cases to the public, other signs of change were taking place: a man was found guiltyby a jury of his peersfor violating the trash ordinance; a dog pound opened and began rounding up Leadvilles numerous stray pit-bull mixes; a committee to fix the pool was gaining momentum; and when a Diversity Committee held a Cinco de Mayo celebration, more than four hundred people attended. It wasnt diversityonly a few non-Mexicans were therebut restaurant owner Frederico Montez, a Mexican who had arrived in 2001, was amazed at the turnout. I didnt know there were so many Mexicans here, he said. It was the first time mariachis ever played in Leadville, he added with a smile.

That fall, the voters chose Bud Elliott for mayor by a margin of just forty-six votesa squeaker, but another sign that newcomers were starting to tip the balance. Within days Bud had twenty junk cars towed, and Leadville didnt riot. The town also passed two school bonds, the first in thirty years. In 2004, voters would face another choice between two opposing visions for Leadville. Chet and Carol both announced their intentions to run for county commissioner when Jim Martins run spanning sixteen years in local government ended.

Leadvilles relationship to Superfund is changing as well. Mention the Wedding Cakes and most residents shrug. The fence along the Starr Ditch is no longer considered the Berlin Wall. The sign had come down long ago. After Mike Holmes sent in a crew to dredge out the sediments and restructure the ditch, he announced that the chain link fence could come down. The response: We dont want our kids playing in that. So the fence stayed. (When Ken Wangerud was told of the residents change of heart, he was stunned. Youre kidding me. Ken paused, then added, Well, you see? Thats why you stand up and you take a lot of shit.)