First published in Australia in 2012 by Hale & Iremonger (an imprint of The GHR Press)

P O Box 612

Brookvale NSW 2100

www.ghrpress.com

This selection, Introduction and the essay Food Copyright Sue Blackburn, 2012

Other essays Copyright the contributors: Craig Campbell, Lori Nielsen, Judy Fander, Nick Bolkus, Tess Driver, David Templeman, Claire Hayes, Jane Burns, Max Lees, Martin Caust, Margaret Kartomi, Julie Anderson, Sue Park, 2012

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher.

National Library Catalogue data available upon request

ISBN: 978-0-86806-930-2

ISBN: 978-0-86806-929-6 (epub)

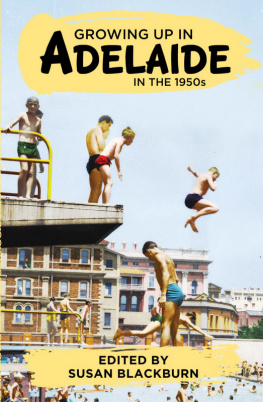

Cover design by Xou Creative

Internal design by Xou Creative

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro and KTF-Roadbrush

Printed by The OMNE Group

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Craig Campbell

Lori Nielsen

Judy Fander

Nick Bolkus

Tess Driver

David Templeman

Claire Hayes

Jane Burns

Max Lees

Susan Blackburn

Martin Caust

Margaret Kartomi

Julie Anderson and Sue Park

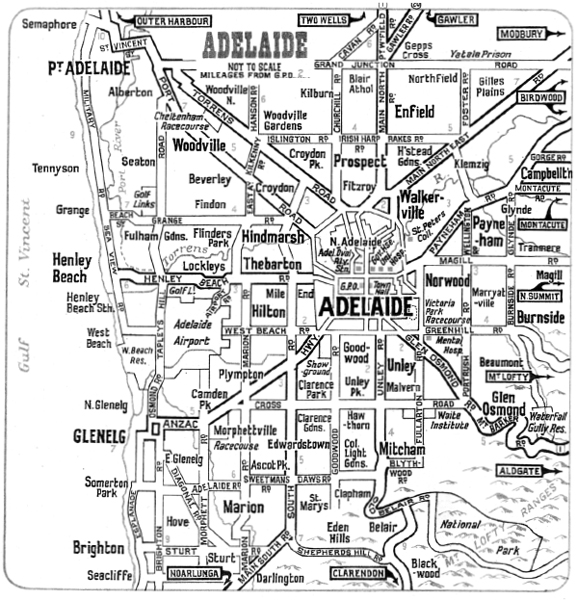

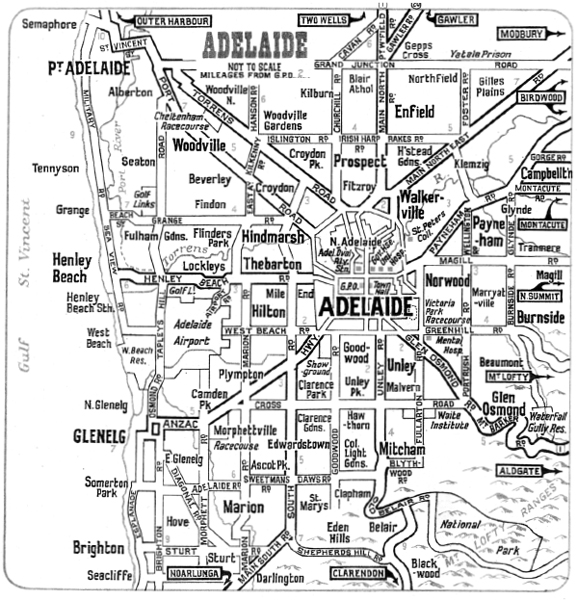

Map of Adelaide 1959. (From Ampol road map of South Australia)

INTRODUCTION

Susan Blackburn

For this book I invited a number of people who grew up in Adelaide in the 1950s to write about their childhood experiences. Rather than their providing straight autobiographical accounts, I asked them to choose a theme which they felt was important for shedding light on some aspect of what it was like to be a child growing up in that time and place, something that evoked Adelaide in the 1950s from a childs point of view. In inviting contributions I tried to find people who had a range of experiences and were various ages during that decade roughly between three and sixteen years old. As I point out below, the full breadth of childhood experiences is not represented here, but there is enough to give a feel for much of the variety. Readers will find some overlap in these accounts, which serves to show what is common to a number of them, but the different themes and the different personalities and circumstances of the contributors ensure that their perspectives and styles of writing vary.

This book should not be compared with the (very limited) literature and memoirs by those who grew up in Adelaide in the 1950s.

Adelaide in the 1950s

There are plenty of common stereotypes about Australia in the 1950s. It is almost always seen, implicitly or explicitly, in relation to the decades that preceded and followed it. By comparison with the thirties and forties it appears to be a time of peace and economic security, of full employment and growing consumerism, and of rapidly growing population, fed by a baby boom and an unprecedented level of immigration. By comparison with the rapid social change of the sixties and seventies, critics often see the fifties as conservative and dull, with rigid gender patterns, and they ridicule the pervasive suburban life of the period as narrowminded and limited. Alternatively, the more nostalgic among us picture the decade as a time when social and religious mores and family life were stable, when everyone had enough work and income, and society was secure and harmonious. In short, the stereotypes imply that you either love the decade or hate it, depending on how much you hanker after a time of stability and slowly growing prosperity.

If those are the stereotypes about Australia in the fifties, what about Adelaide in particular? Adelaide in the 1950s was the fourth largest state capital in Australia with a population of 483,508, according to the census of 1954. In the portrayals of post-war Australia we encounter a layer of frequently negative generalisations about Adelaide. Compared with other Australian cities, in the fifties it is held to be particularly parochial, staid, stuffy, wowserist and conservative, dominated by Tom Playfords long Liberal-Country Party premiership (19381968) On top of this are the persistent geographically based stereotypes: Adelaide as flat and featureless apart from the nearby hills (absurdly called the Lofties), with sparse vegetation and bare, exposed beaches.

The conventional view of Adelaide as neat, old-fashioned and staid is upheld by the view of the central city in 1950, dominated by the towers of the post office and town hall. (Photo: State Library of SA)

Like most stereotypes, these have a basis in fact, but they tend to exaggerate and omit some significant features. Playfords Adelaide was more interesting and dynamic than many give it credit for.

Nurses and babies in 1957 at the Queen Victoria Maternity Hospital, where most Adelaide baby boomers were born. ( Newspix/News Ltd)

People were encouraged to immigrate and have children because of full employment and ready access to housing assisted by the activities of the South Australian Housing Trust.

Migration contributed to population growth only a little less than the baby boom: during the period 194765 the state gained 215,461 immigrants. As Hugo points out, South Australia received a disproportionately large share of immigrants, many of whom were from non-English speaking backgrounds, although Playford gave special assistance to the British, who were still the main group. While in 1933 only 1.5 per cent of the population of South Australia were from non-English speaking countries, by 1966 it was around 11 per cent. The largest groups were Italians, Germans, Greeks and Dutch. In this book, chapters by Hayes and Bolkus in particular show the impact of migrants on parts of Adelaide, although other areas were virtually untouched by the influx of New Australians, as they were called, at the time, because many migrants settled in concentrated locations.

Much changed in Adelaide in the post-war period, not only in terms of population. The workforce was certainly different from before the war, since unemployment was at an all-time low and manufacturing absorbed more than a quarter of the workforce compared to about 15 per cent before the war. One historian went so far as to say of Adelaide around 1960 that, The eccentric, pietistic town that had jogged for years on the sheeps back or the wheat dray was now a marker pin on the map for multinational corporations like General Motors Holden and Chrysler. Chapters in this book by Caust and Lees in particular illustrate the pressure on schools during the 1950s.

With population growth, Adelaide expanded rapidly in size. New subdivisions accommodated much of the housing required. Some of the chapters in this book show the contrast between oldestablished suburbs and new ones: one has only to contrast the environment depicted by Bolkus and Nielsen, for instance, with that shown by Caust and Hayes. One of the causes of its sprawling, low density suburbs was the rise of the motor car after the war and after petrol rationing ended in 1950. Although car ownership could not compare with the level of today (there were still only 12,000 registered cars in 1960), it was significantly greater than in the pre-war period, reflecting the greater affordability of cars.

Next page