First published by Ayni Books, 2019

Ayni Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., No. 3 East Street, Alresford

Hampshire SO24 9EE, UK

www.johnhuntpublishing.com

www.ayni-books.com

For distributor details and how to order please visit the Ordering section on our website.

Text copyright: David Rowan 2018

ISBN: 978 1 78535 764 0

978 1 78535 765 7 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017943402

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of David Rowan as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: Stuart Davies

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY, UK

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

Contents

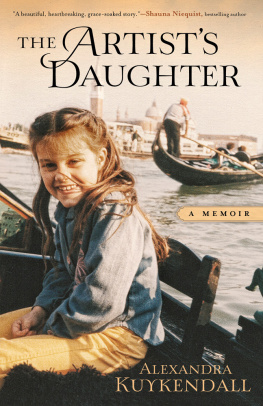

For Brittany, Erika, Julia, and the countless other innocent young women who have lost their lives to these insidious drugs.

For Roz who, ever since that terrible day, has had to endure unfathomable loss.

For Alex, my best friend for 23 years. You didnt deserve to be taken from us like this. Wherever you are, keep making tea, taking notes, and giving hugs. I love you.

Preface

I did not intend to become a member of an exclusive club that you would not wish on your worst enemy, the Club of Parents Who Have Lost Their Children. I did not intend to become an activist, fighting against the injustices of our American medical and drug lobbies. I planned to enjoy a comfortable retirement, quietly fading away with my wife while we watched our lovely daughter Alexandra grow and thrive.

However, in October of 2013, all our plans changed forever: Alex, our only child, died suddenly and without warning. This horrible event has forever altered my life and that of my wife. Everything from that terrible day forward has been completely different from my expectations beforehand, and I began a journey that took me through the darkest times of my life, a journey that continues to this day. Where, when, or if it will ever end, I dont know, but I do know that I have no choice but to travel down a sad and grim road.

When I began writing this book I thought that perhaps it might be some sort of catharsis for me, that it might liberate me, or at least ease my sorrow. But it hasnt. Some of the work brought back joyous memories; some of it revealed things I hadnt known before, and some was terribly depressing to relive, but always, the writing drove home one simple, unavoidable and painful truth: My daughter is dead and she isnt coming back.

She didnt have to die, and the more I learn about the cause of her death and the insidious, commonly available drugs that killed her, the more this statement rings trueshe didnt have to die! I hope that others need not tread my path in their future. I hope that these words will make young women or their parents stop and think. It may almost be a clich to say it, but if just one death is avoided by reading this book, then it will all have been worthwhile.

Finally, I promised Alex that her writings would be published, and some of her work is presented here. It was her lifelong desire to become a published author, and her work is good enough, but this ambition was curtailed by her unnecessary demise. No matter; if she is out there somewhere, shell know that at last she has achieved her goal.

Chapter 1

August 1990Birth

The London summer of 1990 was exceptional; for many weeks temperatures had soared into the 80s. Most Brits, after their first flush of excitement about actually having a summer, were now back into their usual mode of moaning about the weather. Another Scorching Day, No End in Sight shouted newspaper headlines. For Roz, in her second trimester, the heat simply added to the misery of a difficult pregnancy. Lying in bed on the top floor of an old hospital with no air-conditioning, her enforced bed-rest was a taxing proposition and she sweated out the days with her fellow bedmates, staring out across the dirty slate rooftops of the city center.

Although the initial stages of her pregnancy had seemed normal, as time progressed Rozs blood pressure had gradually increased. At first the doctor had simply advised rest. When this had no effect, full bed-rest was ordered. But it was all to no end, and finally shed been admitted to University College Hospital (UCH), an imposing Victorian red-brick complex just off the top end of Tottenham Court Road. Roz knew that this was the right place to be: As a medical secretary in Houston (and in England before wed moved to the States), on our arrival in London shed done research into the many hospitals near our flat and had concluded that UCH was by far the best in terms of prenatal care. Shed even sought out a position there, interviewed successfully, and ended up working at the place. She had thus got to know the ins and outs of its operation; who were the good doctors, who were the not-so-good, the cranky ward sisters and the kind ones. The hospital was an old building with many floors and definitely no air-conditioning in most of its wards. So here she now lay with the other mums-to-be, like rows of beached whales lying on their beds glistening in the heat, all windows opened, table fans whirring, waiting for the contractions to start.

Throughout her weeks of confinement there, my ritual was to climb the stairs each evening and hang out with her for as long as I was allowed. My routine was: board the sweaty, smelly, and crowded Tube near my office at Barbican; ride four stops on the Metropolitan, District and Circle line; exit at Great Portland Street and walk five minutes to the hospital entrance. After my visiting time with Roz ended, I would then make a 45-minute walk up through Camden to our place in Kentish Town, usually stopping off for fish and chips or a kebab on the way. The next day, repeat, and so on. It was a tedious routine, but wed both embarked on our quest for a family with eyes wide open, and we considered our efforts to be worthwhile.

At the age of 39, Roz was relatively old for her first pregnancy, but was in generally good health. Neither of us had anticipated any major problems, although maybe Roz subconsciously did when she researched and selected UCH? Her rising blood pressure was a mystery to us, but not to the doctors: We had never heard of pre-eclampsia, but here it was, putting Roz on full hospital bed-rest. The causes of this sickness are essentially unknown, but the problem affects around 1 in 20 pregnancies, usually showing up in the second trimester and continuing for some time after birth. It was worrying for us both, but not overly so; we simply dealt with it and continued to look forward to our baby.

So, the days and weeks passed, me with my routine, Roz with her boring and sweaty confinement. Meanwhile, her BP numbers quietly continued their inexorable rise to danger-point.

Despite the hot weather, Id been sleeping well, even though our apartment lacked air-conditioning: The long walk home every night and the couple of pints I usually drank along the way all helped get me off quickly once in bed. Following our move from Houston we had bought a two-bedroom ground-floor place on Torriano Avenue in a corner of Kentish Town close to where it merges with Tufnell Park. This area of London is old and working class. There were no leafy gardens and stuccoed mansions for us, just rows of terraced houses that had, for the most part, been converted into flats. Our mid-terrace place was nothing special, but it was all we could afford in the sky-high real estate environment of central London. We occupied the ground-floor garden flat, while the upper two floors had been made into a self-contained three-bedroomed apartment. It was a nice enough place, close to both work and Hampstead Heath, and within walking distance of most of central London. One enjoyable quirk of our home was that it had once been owned by Tom Bell, an English actor best known for being one of the many Doctor Whos on the BBC. We sometimes received breathless fan-mail for him from as far away as Japan. Living and working in the city, we had both learned not to rely on public transport of any kind, and although I had a car, driving was next to impossible. To be more specific, driving was possible, parking was impossible: Whenever we managed to get a spot close to the flat we were always reluctant to go anywhere in the car again and thus lose our sacred parking place. I therefore walked to as many places as possible, including the hospital, resorting to the Tube only when the distance was too great, or when I was especially short of time.