First Skyhorse edition published 2021.

First published in 2006 by Greenhill Books, Lionel Leventhal Limited,

Park House, 1 Russell Gardens, London NW11 9NN

www.greenhillbooks.com

and

MBI Publishing Co., Galtier Plaza, Suite 200, 380 Jackson Street,

St Paul, MN 55101-3885, USA

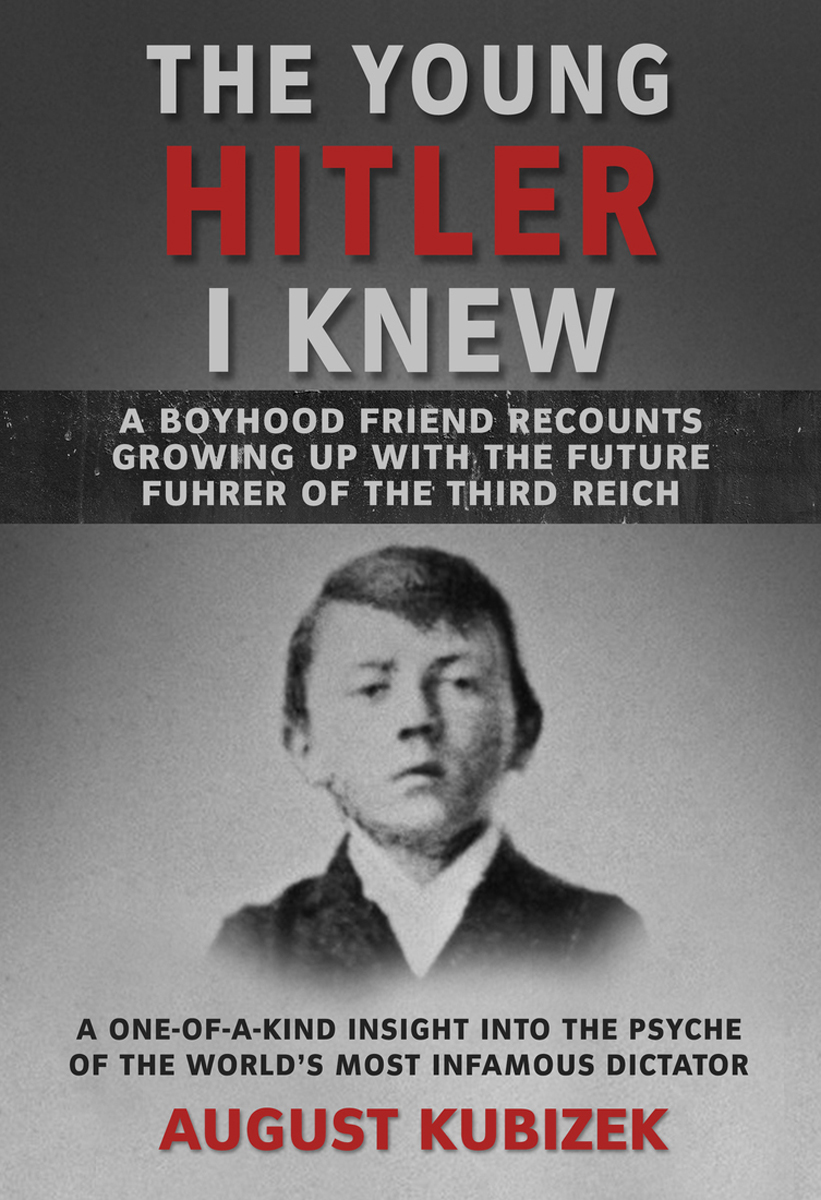

Copyright August Kubizek, 1953

Translation Lionel Leventhal Limited, 2006

Introduction Ian Kershaw, 2006

The right of August Kubizek to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries about this edition should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of

Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

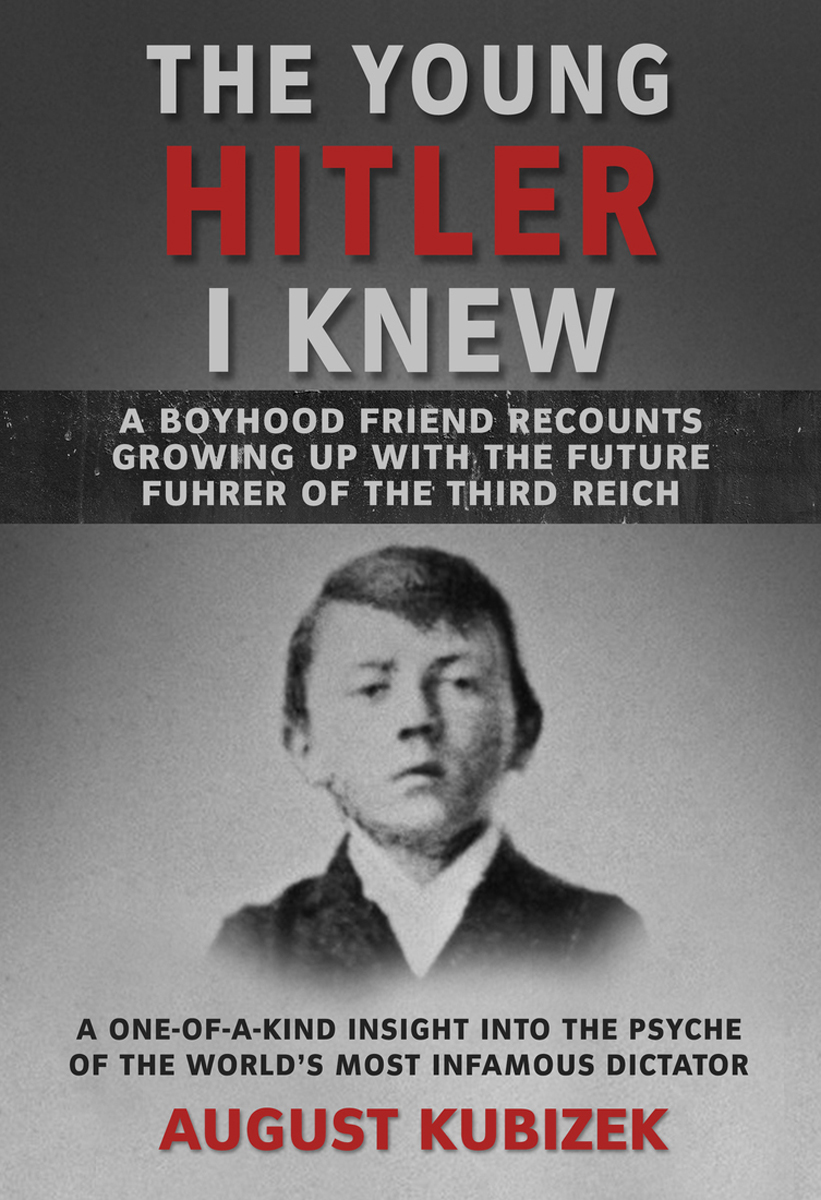

Cover design by Kai Texel

Cover photo credit: Getty Images

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-6263-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-950691-73-9

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

by Ian Kershaw

Illustrations

Introduction

For a vital phase during the early years of his life, his late teenage years in Linz and Vienna, when we otherwise have tantalisingly little to go on, Hitler had a personal and exclusive friend, who later composed a striking account of the four years of their close companionship. This friend was August Kubizek. His account is unique in that it stands alone in offering insights into Hitlers character and mentality for the four years between 1904 and 1908. It is unique, too, in that it is the only description from any period of Hitlers life provided by an undoubted personal friend even if that friendship was both relatively brief and almost certainly one-sided. For, like everyone else who came into contact with Hitler, Kubizek would soon learn that friends, like others, would be dropped as soon as they had served their purpose.

For every study of Hitlers early years, including the first parts of my own biography, Kubizeks story has proved an indispensable source. His recollections of his time together with Hitler, first published in 1953, are now in their sixth edition. An English translation, with an introduction by H. R. Trevor-Roper, later Lord Dacre, was published in 1954 and later reprinted, and has had to serve for those without access to the German original until the present. Yet this earlier English-language version was neither a complete nor an altogether satisfactory translation of Kubizeks German text. Numerous passages, in fact some entire chapters, were omitted. This new translation remedies these deficiencies and omissions. For the first time, it makes the entire text of Kubizeks recollections of his friendship with Hitler available to an English readership. This is greatly to be welcomed.

August Kubizek was born in Linz in 1888. After leaving school he served as an apprentice in his fathers small upholstery workshop. But he was musically talented, and this offered him an exit-route from the upholstery trade. While the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna was rejecting his friend Hitler, Kubizek was gaining entry to the Vienna Conservatoire to study music. He subsequently obtained a position as second conductor in the municipal theatre at Marburg on the Drau, and was just married when war broke out in 1914. He served in the Austrian Army for the duration of the war, suffering a serious lung infection in 1915 from which he never fully recovered. After the war he became town clerk of Eferding, near Linz, where his duties included organising the small communitys musical events. And there he remained, a quiet, retiring family man, helping to bring up his three sons, and conscientiously involved in the local cultural life.

In the meantime, his erstwhile friend had become famous. Kubizek sent a note of congratulation when Hitler became Reich Chancellor in January 1933, and later received a personal reply. Hitler even suggested that Kubizek might pay him a visit one day. Nothing came of this for five years. But shortly after the Anschluss, Kubizek made his way to Hitlers hotel in Linz, and was allowed in to see his former friend for the first time since their ways had parted in 1908. Hitler greeted him warmly though now used the formal Sie mode of address not the more intimate Du (which he had still used in his note to Kubizek five years earlier). Invitations followed to the Bayreuth Festival in 1939 and again in 1940, when, with Hitler at the height of his power, he and Kubizek met for the last time.

Kubizek had by then gained recognition among leading Nazis as a friend of the Fhrer as a young man, and was known to have memorabilia from that time. He had already in 1938 been approached and agreed to write his recollections for the Party archive. His insights were said to be staggering, revealing the inconceivable greatness of the Fhrer in his youth.in Eferding. These became the basis of the book, Adolf Hitler Mein Jugendfreund, published in 1953, and an immediate sensation. Kubizek died three years later, now widely known as a first-hand witness to Hitlers early, formative years.

But how valuable is Kubizeks book as a source for Hitlers life in Linz and Vienna? The core of the book, we should recall, began life as a manuscript commissioned by the Nazi Party. A copy of the second part of this original text survives today. The Austrian publishing house denied that it had provided any assistance. But either Kubizek suddenly discovered the art of writing, or he had help from a person or persons unknown.

Kubizeks recollections need to be read critically and treated with great care for other reasons. The young Hitler, for example, is frequently and extensively cited verbatim in Kubizeks published text (though seldom in the original manuscript). Kubizek is far from alone among those who later wrote of their experiences of Hitler in putting words directly into his mouth years after the events described. But it is self-evidently impossible that he could have remembered exactly what Hitler said over four decades later. The direct quotations have, therefore, to be seen as a literary device of Kubizek (or his ghost-writer) rather than precise expressions of the young Hitler. This does not in itself discredit their veracity as statements of Hitlers views. But, obviously, they ought not to be taken at face value as quotations.

Beyond this, some of Kubizeks recollections have more than an air of fabrication about them. His story of Hitler denouncing to the police a kaftan-clad Jew was probably an embellishment of a well-known episode in Mein Kampf (on which Kubizek drew quite extensively in his book). The description of a visit together with his friend to a synagogue sounds equally dubious. The claim that Hitler joined the Anti-Semitic League in 1908, and registered Kubizek for membership at the same time, is plainly wrong. No such organisation existed in Austria at the time. Kubizeks passages on Hitlers anti-semitism, in fact, deserve generally to be treated with scepticism. They are clearly designed to distance himself from his former friends radical views (which he, almost certainly wrongly and in contrast to Hitler himself, dated back to the influence of home and school in Linz), though his own anti-semitism had not been concealed in the manuscript version.

Next page