Table of Contents

For Radhika (Canna) Sharma and

Joshua Ghosh Stephenson

Contents

S cent of a Story is more or less a true story. More or less, because for the early part of the story I have reached out into the past and tried to string together fragments of half-remembered conversations and incidents from my childhood. Thakurma (grandmother), Kumudini in the book, was a dear friend and even after an exhausting day would find time to tell stories till I dropped off to sleep. These stories ranged from fairy tales to bits of her real-life experiences, the latter related in a matter-of-fact manner as if sharing confidences with a friend.

Mother was a happy person, happiest whenever she found time to read. Summer afternoons I was her captive audience, and would listen to her recitation of Tagores poems. Sometimes the poems would lead to her early days as a bride when she used to recite these same poems to my father, and the fun and heartbreak they shared together. On most days this session would end with her nodding off and my sneaking off, on tip-toe, to the lawns outside, to my favourite perch in the fruit-laden guava tree.

Father was a great raconteur and the dinner table was a great place for listening to his stories. The evening would usually start with my father asking for our opinion on the days editorial in the Pioneer and the immediate response would be a delirious appreciation of the incisive observations and his superlative use of the English language! Unfortunately, our preoccupation with the sports pages and cinema advertisements, and very little else, would be found out the next moment when he asked us to talk about the edit!

Father would always see and share the funny side of things; perhaps that is why so much of the dinner table conversations are still fresh in my memory. We became the best of friends perhaps we always were and when one of my daughters, who was staying with my parents, decorated a not-so-good school report card with her own guardians signature, he took it upon himself to explain to the school nuns that age had ruined his handwriting and each signature would come out different! He told me later with a wink that he couldnt do anything different now than what he had done when I as a child had once also signed my own report card!

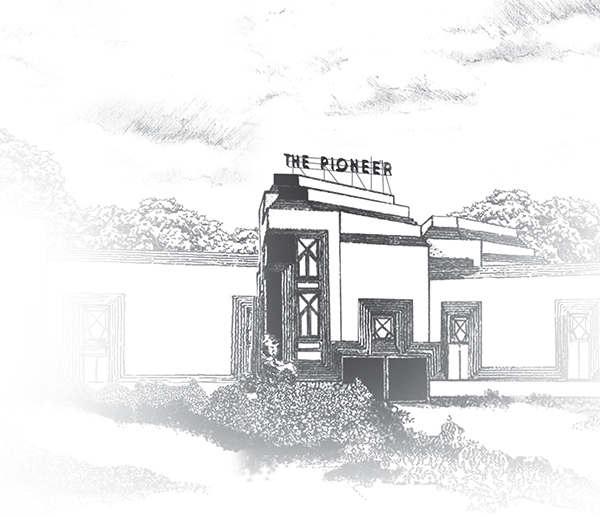

It was a unique experience to grow up in the Pioneer building in Lucknow designed by the iconic architect Walter Burley Griffin. Very few people remember Griffin and his contribution to the architectural design of some outstanding buildings in Lucknow. I too would never have known about him if it hadnt been for my father who told me about him and showed me his then unmarked grave in the Nishatganj cemetery.

My home wasnt just the editors flat. The editorial staff didnt mind me quizzing them on the stories of the day and my precocious suggestions for headlines. The main hall which housed the printing and works department was a place of wonder, an Aladdins cave where everyone tolerated a pyjama-clad urchin scrounging around for the bright round lead pellets which had spilt over while pouring out the melted ingots and served as excellent catapult ammunition. On rare occasions I could cajole Shyam babu to let me operate the Linotype machine, and the ever-smiling Kesho Lal and Mr Alburn, foreman (works) and works manager respectively, would allow me to enter the pit of the rotary machine after the print run. The swathe of newsprint, hanging like sails under the rotary, was an ideal place to pretend that I was the captain of a pirate ship leading a thieving bunch of scallywags for pillage and plunder. Of course, cross my heart and hope to die, never a word to my parents!

When I got down to relate this story, I was in a bit of a dilemma. How should I go about it? Should I try and write it from an observers point of view, or should I write it as if I were being the storyteller. A third option seemed most appropriate. Why not voice it in my fathers words, as that is how I remember most of the incidents. This story is, therefore, written as a first-person narrative of his life as a newspaperman through the tumultuous years of twentieth-century India, through the times of the viceroy and princely India to a modern democratic nation.

I would like to acknowledge with thanks the wonderful people of the Pioneer I had occasion to interact with, and who have helped me capture the flavour of the times and write this story. Grateful thanks to daughters Madhumita and Sucharita for helping me tide over very frequent afflictions of the writers block. To my wife, Manju: thank you for your help in filling some blanks in my memory. My thanks to young Joseph Antony for a great job editing the manuscript. And a big thank you to Krishan Chopra of HarperCollins Publishers for his encouragement and contagious belief that I had a story to tell.

H er school, a brick-and-thatch affair in a church compound, had two classes: choto class (small class) and boro class (big class). Very fair, tall and all of twelve years, Kumudini had finished choto class. She considered herself fortunate that her parents allowed her to attend school, unlike most of her friends who were already assisting full-time with household chores. She was a bright student and the missionaries had promised her that they would speak to her parents: After boro class, God willing, they would send her to Bilate (England), for formal education.

On that day, beside herself with excitement, she didnt stop to listen to the nun play the piano after class, and ran home, with the anchal of her blue-bordered sari fluttering behind her as she ran. It was a Saturday, and she didnt have to avoid the puddles and save her sari from being soiled the sari could be washed the next day.

She was panting heavily by the time she reached home and splashed the metal-tasting water on her face from the hand pump. It wouldnt do to appear dishevelled, her father was home, and hadnt she heard her age being discussed so many times? She had to behave with decorum and remember not to look him in the eye when telling him about what the memsahib nun had told her. Oh it was all so very complicated, it would be better to talk to her mother.

Late afternoon, on hearing her father snore after his midday meal, she joined her mother in the kitchen. Her mother had kept some rice and vegetables for their meal and was about to clean the cooking pots. Kumudini joined in with scraps of coconut coir and ash. She was hungry, but the sense of camaraderie she felt while helping her mother was to make the dam burst. Ma, the memsahib nun has told me that, after boro class, the church would try and send me to Bilate for higher studies. What fun, no?

O Ma! You will lose your caste, her mother Nalinibala replied, her voice filled with anguish. They will convert you to Christianity.

Lunch was forgotten, and Nalinibala now rubbed ashes on her forehead, and rocked back and forth on her haunches reciting gayatri mantra.

Kumudinis father, Babu Gopal Chandra Dey, worked in the main post office in Allahabad and was a first-generation settler in north India. He would have never left home in Calcutta if it had not been for an act of God, an act which wiped his slate clean of friends, relatives and all material possessions.