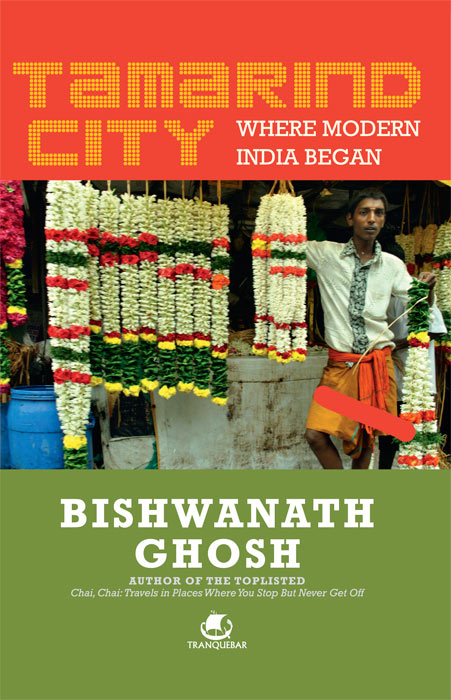

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

Tamarind City

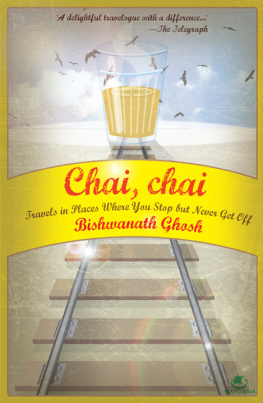

Bishwanath Ghosh was born on 26 December 1970 in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, where he began his career as a journalist before moving to New Delhi to work with the Press Trust of India and The Asian Age. In 2001 he relocated to Chennai where he spent seven years at The New Sunday Express and three at The Times of India. He is currently a deputy editor with The Hindu. In 2009 he wrote the bestselling travel book, Chai, Chai: Travels in Places Where You Stop But Never Get Off, also published by Tranquebar.

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

An imprint of westland ltd

Venkat Towers, 165, P.H. Road, Opp. Maduravoyal Municipal office, Chennai 600 095

No. 38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bangalore 560 026

Survey No. A-9, II Floor, Moula Ali Industrial Area, Moula Ali, Hyderabad 500 040

23/181, Anand Nagar, Nehru Road, Santacruz East, Mumbai 400 055

4322/3, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

First published in TRANQUEBAR by westland ltd 2012

Copyright Bishwanath Ghosh 2012

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-93-81626-33-7

All photographs by Shruthi Venkatasubramanian except those indicated otherwise

Typeset by Arun Bisht for Four Words Inc

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

For two women in my life:

My mother Karabi,

who did not live to see this book,

and my wife Shuvashree,

who saw me through it.

CONTENTS

Company Comes Calling

North of South

Do You Believe in God?

A Sacred Sunday

Sex and the City

The Rich Girl and the King of Romance

Chandamama and Madras Miscellany

A Seaside Story

Come December

All Roads Lead to Chennai

My Street 298

When writing about a city you are still living in, you dont have the luxury of looking back at it from a distance, with a boxful of notes and memories to draw from. You live your subject each day, and one of the biggest challenges is to sift through your daily life to collect material that may be used to paint a portrait.

This book, however, does not pretend to be an exhaustive or authoritative study of Chennai or of Tamil culture. It is born purely out of my desire to understand a city Ive called home for over a decade now.

B.G.

PROLOGUE:

THE TRAIN TO A

NEW IDENTITY

A t times, even a minor act of nature can decide things of great significance to some of ussuch as the title of this book.

One morning around six oclock, when the roads of Chennai are stirring awake, wife and I were driving home after dropping a friend off at the railway station. Rarely do you find yourself driving at a leisurely speed in your own city at that hour; usually it is a dash to catch a plane or train, when the eyes are glued to the watch and blind to the blossoming of a new day.

We were on Commander-in-Chief Road, gliding towards Mount Road, when something fell from a tree straight onto my lap. Taking it to be a large insect, I instinctively shook it off. As the tiny intruder lay near my feet, I examined it from a distance and then picked it up with glee.

Whats that? my wife, who was driving, asked.

A piece of tamarind.

But why are you smiling?

Because that settles it.

Settles what?

I had just signed the contract for this book, intended to be a portrait of Chennai, which I proposed to call Tamarind City. The title was based on my childhood impression of the city. However, when I bounced it off my well-wishers in Chennai, they all, quite expectedly, raised the same argument: But tamarind is not unique to Chennai, it is commonly used all over south India. That set me thinking: should I be fastidious about such technical accuracyeven though Chennai has traditionally been representative of the whole of the south and therefore qualifies as Tamarind Cityor celebrate the image that was sown in me as a child?

For weeks, I see-sawed between Tamarind City and the various names that came to mind at odd times of the day. I visualised these titles on the spine of an imaginary book, but none of them was convincing enough to make me saythis is it!

Then, that morning, the balance was tilted by a weightless piece of dry tamarind that fell straight from the tree onto my lap. I knew this was it.

I was thirty, single and commitment-phobic when I moved to Chennai in 2001. I was hoping to spend a few carefree years in the city before returning to Delhi to settle down. But Chennai turned out to be a rocking chair. Swinging to its gentle rhythm, the balmy sea breeze always apologising on behalf of the heat, I didnt realise how quickly the last two digits of that year got interchanged.

Today I am forty, married, and leading a fairly comfortable existence as an honorary Madrasi. Yet, as I look into the mirror every morning, stroking the new grey sprouting on my chin, I often find myself asking: But wasnt it only the other day I took the train to Chennai?

I had almost missed the train.

Delhi lay under a thick blanket of fog on the night of 13 January 2001, when I arrived at the railway station to board the Tamil Nadu Express. I was to travel 2,157 km in the next one-and-a-half days to reach Chennai. A small party of friends, including my girlfriend, had come along to see me off. They engaged me in humorous banter as we stood in a circle on the platform. Much of the ribbing was forced, just to break the awkward silences that we kept slipping into. They were aware, as was I, that for all the years we had spent together, I would be past tense once the train pulled out of the station.

The trains departure was scheduled for 10.30 pm, but there was no sign of the train even at ten oclock, which was unusual. Trains originating from a station usually park themselves at the designated platform way ahead of the departure time. Finally, the recorded female voice, the nightingale of Indian Railways, announced a delayfirst by thirty minutes and then by an hour.

The delay, presumably due to the fog, was robbing my departure of drama. I could see my friends growing weary of waiting. The banter was now too artificial for comfort. A farewell is most effective when short and sweet; the longer it drags, the more you wish the person left sooner.

To make matters worse, a male voicelive and not automatedcame on the public-address system to announce that the departure of Tamil Nadu Express had been postponed indefinitely due to the dense fog engulfing north India, and that passengers must wait until further announcement.

I could see the smiles vanish from the faces of my friends. They were friends alright, but why should they stand indefinitely in the bone-chilling cold to wave goodbye to someone they might never see again? They bullied me into going back to my girlfriends place, which was very close to the railway station, and advised me to keep checking the trains departure time over phone. The girlfriend was delighted. She had earned a few more hours with me. She perhaps knew the relationship was eventually going to be devoured by distance. As soon as my friends dumped me back at her place and left after giving me farewell hugs, having fulfilled their responsibility of seeing me off, I called up the station. To my horror, I was told that the Tamil Nadu Express was leaving in thirty minutes.

Next page