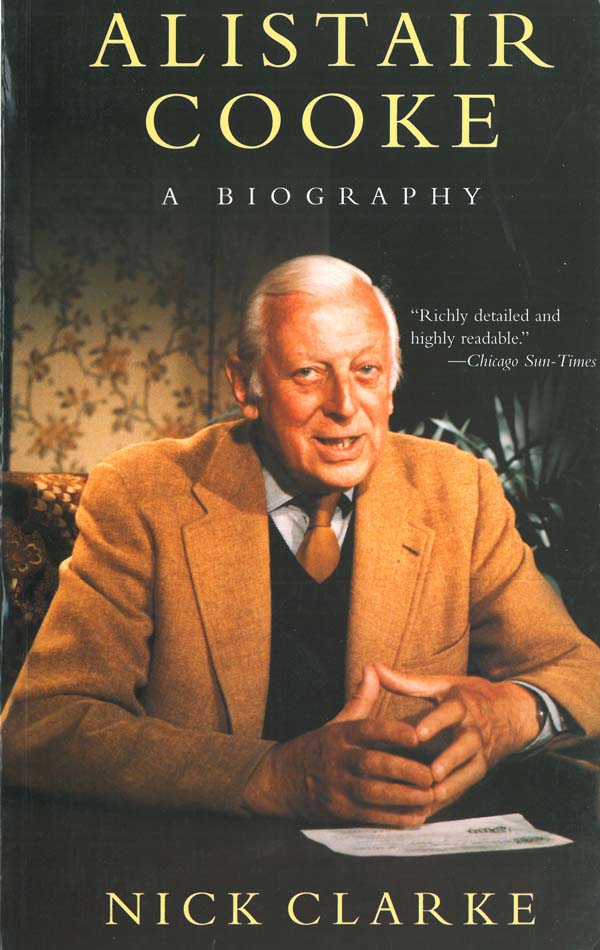

Copyright 1999, 2011 by Nick Clarke

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

First published in Great Britain by Weidenfeld & Nicholson

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com .

10 9876543 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-642-4

For Barbara.

And in memory of my father

and mother, John and Ruth.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The majority of photographs come from ACs voluminousif haphazard collection with the following additions:

Between pages 116 and 117

I am grateful to Kathleen Turner (ne Cooke) for a number of the family groups and to William Whalley for the victorious Blackpool rugby team. David Curnow provided the splendid Old Blackpoolians dinner.

Between pages 180 and 181

A number of the Cambridge photos, especially those celebrating The Granta magazine and the Mummers, came from Eddie Wiltshire, Hugh Stewart and the late Norrie Davidson.

Between pages 244 and 245

I was delighted to have the shot of Ruth Cooke in Ibiza, and the Southold Sunday Lunch, from John B. Cooke. Ruth herself unearthed the evidence of her modelling career.

Between pages 308 and 309

John Cooke found the post-war shot of Cookes parents and brother. The David Low cartooons hang in the Bunker at Nassau Point and the Omnibus sequence comes from the extensive archives of Roy Stevens in New York.

Between pages 372 and 373

Several of the photographs in this section were taken by Leonard McCombe in the early 1950s: he very kindly allowed me the pick of his portfolio. The shot of AC in his study was taken by John Cooke.

Between pages 436 and 437

Pictures from the making of America are from the BBC Stills Library in London. John Cooke caught his father playing golf in the hallway of his Manhattan apartment. Colin Clarke provided the shot of AC with Prince Charles, and Freddie Hancock entrusted me with her prize photoBernstein and Galway in concert. Thanks also to Masterpiece Theatre for the farewell party, to Heather Maclean for Bedside Broadcasting and to the Huntington Hotel, San Francicso, where Janes protrait of AC hangs. Some of the later snaps are my own.

Caricatures

The caricatures which appear at the beginning of each part were drawn by AC himself and correspond roughly to the relevant period of his life. The hangman drawing (Part Three) was used to decorate his wedding invitations.

INTRODUCTION

One Thursday afternoon in the summer of 1994, I waited anxiously outside a BBC Radio studio at Broadcasting House in London, where Alistair Cooke was recording a Letter from America. From the corridor, it was possible to catch the rise and fall of the familiar voice, but not to hear the words. I had been warned that Cooke disliked being overlooked or overheard while he was delivering his script: the producer and sound engineers were allowed to listen, but only under sufferance. Critics and reviewers had often noted this insistence on the intimacy of his art - the art of speaking directly, and without distraction, to each individual listener. None of which was much help to the would-be biographer, pacing the faded carpet-tiles, and wondering how to broach what was likely to be an unwelcome subject.

Cooke, I had read, was a private man with a tendency to prickliness, but when we were finally introduced, he was courteous to a fault. We exchanged conversational niceties - about golf and the prospects for Wimbledon - until the moment could be deferred no longer. What did he think about the suggestion that I should write about his life? Cooke did not think much of it, and was not afraid to tell me so. I should choose somebody more interesting, or dead, or both. Einstein might be a good subject, or the golfer, Bobby Jones.

Later that week Cooke did agree to meet me at his rented apartment in Mayfair, where he plied me with absurdly strong gin - being a whisky-drinker himself - and regaled me with tales of politics, publishing and the BBC. The anecdotes whetted my appetite, and emboldened me (after more than two hours) to ask my question again. Cooke smiled sympathetically, gently informed me how often he had deflected such advances in the past, and let me know that he had no intention of being more compliant this time. I retired, slightly shakily, with a vague promise of some conversations on specified topics at some unspecified future date. I was still sufficiently in possession of my faculties to recognise that I had been turned down.

That might have been that, if it hadnt been for the determination of Richard Cohen, whose idea the book was, and John Coldstream, Literary Editor of the Daily Telegraph, who had proposed my name as the writer. Cohen believed mat it was worm persisting, and encouraged me to delve into Alistair Cookes roots in the North of England. In due course, I began to unearth fragments of his early life before, during, and after the Great War: a Salford Sunday School picture, an old classmate from Blackpool, a long-lost niece. I kept Cooke informed of my progress, and after six months he finally cracked: if the book was going to happen anyway, he concluded, it might be better to ensure - as far as possible - that the biographer had his facts straight.

From that time on, I had access to all Cookes papers, photographs and archives, and I was able to speak freely to his family and friends on both sides of the Atlantic. Without that co-operation, this book would not have been possible. Whats more, Cooke made no effort at any time to influence the course of my work: indeed, he always claimed that he had no intention of reading it. I am properly grateful for his initial act of faith, which - as he often told me afterwards - he immediately regretted.

Nick Clarke

June 1999

PROLOGUE

Alistair Cooke is his own invention.

The voice of the Letter from America, purveying word-pictures of his adopted home back to the land of his birth, is deceptive. So, too, is the elegant figure of an archetypal Englishman, which so many Americans recognised in the host of Masterpiece Theatre. Neither image of the man tells the whole story.

To begin with, he wasnt even Alistair Cooke, having been christened - in November 1908 - plain Alfred. The 'Alistair came later, part of a long and slow process of osmosis.

The first concrete evidence of this process appears on the inside cover of a moth-eaten history textbook - Pages of Britain s Story, AD 597-1898. A bookplate with a school motto and crest bears the name of its owner, neatly inscribed: 'A Cooke, Form IV x. But just above, in bold capitals, a fourteen-year-old hand has doodled a more extravagant signature: 'Alister Alfred Cooke.