This editon first published in paperback in the United States in 2012 by The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Stree

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales please contact

Introductions and all Letters from America copyright

The Estate of Alistair Cooke, 2008

All Guardian reports The Estate of Alistair Cooke, 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-176-2

I am a reporter of the facts and the feelings that go into the American life I happen to observe. I mention the feelings if only to stress a belief that there is no such thing as an objective reporter. But the way to be as fair as possible is to notice that no fact of human life comes to you uncoloured by what people feel it means.

Letter From America No. 831, 9 August 1964

I have often been asked what it was like to grow up surrounded by famous people. It is a question that leaves me dumb. Four-year-olds havent the faintest idea what it means to be famous or infamous; they either like someone or they dont and judge people with uncanny clarity on their warmth, friendliness and approachability. I have found that, with allowances for circumstance and history, most people are pretty much alike, driven to greater and lesser degrees by fear, longing, ambition and desire.

As a child, this is how I viewed the adults who flowed through our house and my world: as nice or not so nice, fun or distant. My view of my father is, therefore, much the same: seen through my own very personal lens. Regardless of whatever else pulled on his coat-tails, when I was little, like all children, I just cared about how much attention he was paying to me.

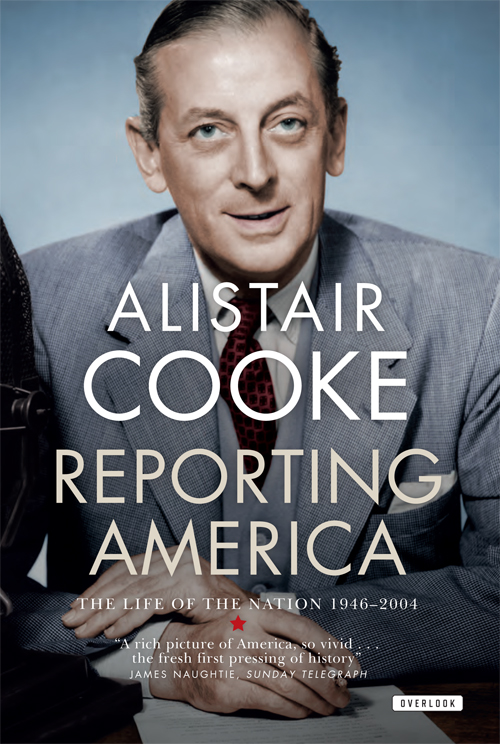

When my father died, accolades flowed and many an erudite observer sought to delineate, once and for all, if not the role he played in furthering international understanding, then at least his influence on broadcasting and reporting in the twentieth century. Because that was what he was, first and foremost: a reporter. It was how he described himself, often with a marked vehemence: I am not a television personality, I am a reporter. A reporter! The more refined title of journalist never sat as well with him as the simple, descriptive term of reporter. I dont comment, I dont judge, I report.

This book seeks to honour what he valued most, reports filed in print and broadcast over the air about what he observed in his assigned and chosen territory: the United States of America. It begins as the Second World War ends, with the sun rising on the second half of the twentieth century. It is divided chronologically into decades, each section presenting pieces from that time. In keeping with this somewhat arbitrary though useful framework, I will loosely also look back by decades to my life with my father, relating, as best I can, not the events and facts I shall leave that to the reporter but what was going on at home. Though I would not presume to know with certainty what Daddy was feeling or thinking, I feel comfortable in sharing my impressions. They are offered as just that, for in the end I can speak for no one else.

As my reflections in this book are primarily about my life with my father, I have not addressed our broader family life. My parents had each been married before and had children from their first marriages; my mothers children are Holly and Stephen and my fathers son is John. Holly and Stephen lived with us, and John with his mother, Ruth. It may seem from the stories I tell that I was an only child; this was in some ways true and in others decidedly not. But Holly was eleven years older than I, and Stephen and Johnny both, coincidentally, eight, a span of years that seemed enormous when we were young. Stephen went away to boarding school when I was three and Holly to college when I was eleven, and although I couldnt wait for their return for holidays, for most of my childhood I was the only child at home. So many of my early memories relate to stories I have been told, making it difficult to know exactly if I really remember the event myself or if it simply has been implanted time and again by others and by familiar photographs.

One of the earliest memories I have of my father was of Sunday nights. In the early 1950s his star was rising; he was a regular correspondent for The Manchester Guardian, his radio broadcast, Letter From America, seemed pretty secure, and he was the host of a television programme called Omnibus. My impression that his feet seemed rarely to touch the ground was probably correct. He was a tightly strung, lean, energetic and engaged man at the time, whose focus, ambition and intelligence had secured for him a stronghold in New York City. Though his commitments were certainly demanding, taking him away from home a considerable amount of time, what I recall was that when he was home the air was charged with vitality.

At no other time was this more true than on Sunday nights. Omnibus was broadcast live, and after each show a slew of the crew came to our house for dinner, always the same fare: chili and beer. High on the excitement of the show, elated that it was over, and not yet under the weight of the next weeks production, they were a very merry and raucous group. My bedroom at the time was a maids room just off the pantry. The pantry led to the dining room, and if I lay at the end of my bed, opened my door just a crack, and made sure that the door to the dining room was also open, I could watch a section of the table and feel part of the gaiety. Generally I was in bed before the crew even arrived at the apartment, and I remember Daddy coming in to kiss me goodnight and ask if I had seen the show. His entrance into my dark slice of a bedroom was like a thunderbolt strike, and I would jump on the bed with excitement. Later I would drift off to sleep on the waves of laughter and camaraderie, the smell of chili, the sound of my mother bustling in and out of the kitchen. To this day several people from Omnibus remain close friends of our family.

During the 1950s it seems to me that the initial elation my father felt at his rising good fortune began to give way a bit to the sobering reality of all he had taken on. As one of the first real television personalities, he was often asked to speak about the evolving medium. As Omnibus struggled for survival and sponsorship, his impatience with the hard realities of its financing grew. He was barraged with offers to lecture on a variety of topics, play parts in films and write for various periodicals and magazines. He was in great demand, and there pervaded in the household an understanding that we cut him a wide berth. This was essential since he worked in the apartment, the doors to his study remaining closed from the moment he awoke until he shut up shop in the evening. We were keenly aware that what was happening within his study was none of our concern. This work routine would remain intact until he gave up Letter From America in February 2004, a week after he was diagnosed with cancer and only a month before he died at the age of ninety-five.