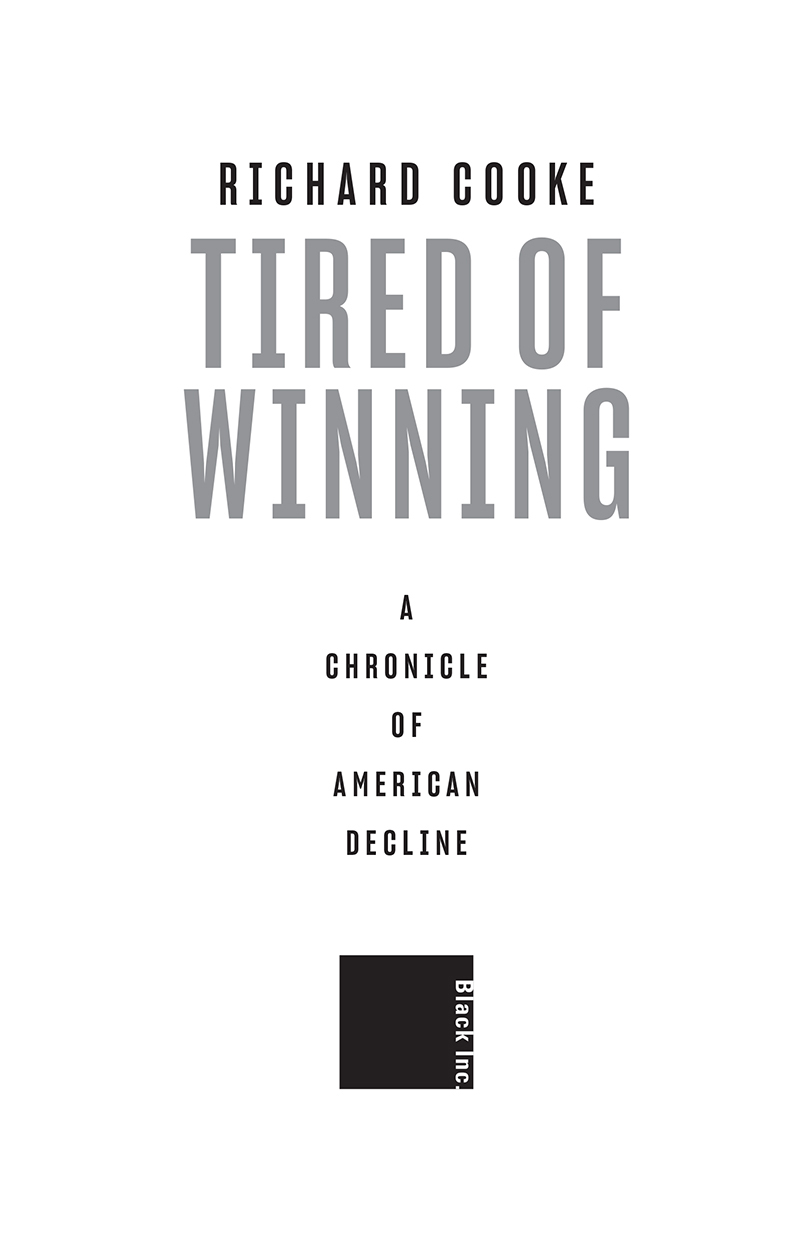

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

Copyright Richard Cooke 2019

Richard Cooke asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

Quotations in this book appear as in the original sources, including any spelling or grammatical errors.

9781760641146 (paperback)

9781743820834 (ebook)

Cover design by Akiko Chan

Cover image Getty Images

Text design by Tristan Main

Typesetting by Marilyn de Castro

To Loulou

Were going to win so much. Youre going to get tired of winning, youre going to say, Please, Mr President, I have a headache. Please, dont win so much. This is getting terrible.

Donald Trump, South Carolina (2016)

And Pedlar Forrest shot Jim Gym.

And Jim Gym shot James McBride.

And James McBride shot Cyrus Partovi.

And Cyrus Partovi shot Lewis P. Bohler.

And James Earl Ray shot Martin Luther King

J.G. Ballard, The Generations of America (1968)

AUTHORS NOTE

T he impulse to write this book began with a failure. I visited the United States before, during and after the 2016 presidential election campaign and did not understand what I saw. After leaving the country, this feeling nagged at me until I returned, eighteen months later, in the lead-up to the 2018 midterm elections. This time, I was determined to experience as much of the present state of the United States as I could, and to capture that experience on behalf of those similarly perplexed.

I felt there was more than enough reporting on the US president without adding to it. The harried ranks of foreign correspondents were thinning, and the survivors sometimes seemed trapped in New York City and Washington, D.C., as though permanently assigned to the presidents Twitter feed. Meanwhile, the relayed images of the United States beyond this unpromising horizon were becoming lower and lower in resolution. Midterms are given less weighting than contests for the White House, but they are seldom less consequential, and the 2018 ballot was the most important in a generation. It was a referendum on Trumpism rather than on Trump, and its diffuse and fragmentary nature meant a book could be written around it, rather than about it, and across a wider landscape than a few battleground states.

The question what is the United States like today? also turned out to be of domestic interest. It is not rare for metropolitan Americans to visit the heartland or the South, but it is not common either, and the coast-dwellers were the people most curious to ask me about what it was like. The tone of these discussions was not hopeful (So are we fucked? was a standard enquiry after a couple of drinks) and one eminent historian asked me, not as an exercise, if I thought there would be a second Civil War soon. I said I didnt know, and twenty states later I still dont.

Decline is a laden word, especially in the subtitle of a book, and its possible that Gibbon and Spengler have given it a permanent taint of melodrama. But I can think of no other way to describe the conditions I encountered. That decline may be temporary, relative, aberrational or partial, but it is real. In some places it made me despondent; elsewhere, resilience and rebirth leavened my pessimism.

One indicative episode: near missions end, I was in Arcadia, California, and on a single day found myself within driving distance of both the site of a mass shooting and the front of an unprecedented forest blaze. I did not get in the car: I had met my grim quota of these acts of god and man many months earlier. When I read reports of the shooting some of the dead had survived a previous spree killing in Las Vegas the targeted advertising on my computer offered up a bullet-resistant childrens backpack. That object should not exist.

I am not sure what to call the dispatches that make up this book. Other languages have more nuanced and adaptive names for hybrids of reportage and essay, writing that modulates between reporting and reflection, but in English we are stuck with catch-alls: accounts, reports, missives. At least two of my countryfolk Robert Hughes and Maria Tumarkin have combined thematically linked essays into mosaic pictures, and this approach suits topics that are too expansive for a unitary theory. My own subject, America in the twenty-first century, is also on this scale.

So what business is it of mine? Being an outsider has its advantages, and there is a long tradition of interlopers shrewdly chronicling America, dating all the way back to Alexis de Tocqueville. My nationality helped my cause as well: I was familiar my country shares a cultural affinity with the United States but not familiar enough to breed contempt. As an Australian, I was seldom received as a representative of the media elite, and there were times when natural selection broadened my accent into Crocodile Hunter territory. I should also mention, though it is distasteful, that white privilege has its uses. Even spatially it functioned as an access-all-areas pass, and it accounts for some of the things people were willing to say to me out loud.

I did not set out to assemble a prosecutorial brief, or to indict a nation and its citizens. Instead I took my bearings from history in particular, I thought of the symmetry offered by the year 1968. That season of tumult, violence and change in the United States makes the present look survivable, if not surmountable. But when I met witnesses to this time, they invariably said things were worse now than they were fifty years ago. This might be recency bias its difficult to recall the pain of unfresh wounds but I think there is a special, twice-bitten form of distress in the current scenario, in its abandoned promises, unrealised dreams and misappropriated resources. In the 1990s, John Berger could write that the poverty of the twentieth century was unlike that of any other time, because it is not, as poverty was before, the result of natural scarcity, but of a set of priorities imposed upon the rest of the world by the rich. In the twenty-first century, the abyss between what could be and what is has extended further still.

It is true that America was never great for Americans of colour (or others who found themselves subject to its sadisms) and that the Make America Great Again phenomenon is only a new version of an old nativist tendency, rather than some novelty emerging from the ether. But I think any cold comfort offered by familiarity is chilled further by an abiding sense of failure. More than fifty years on, the aims of the Civil Rights Act and the Great Society the elimination of poverty and racial injustice are so far from realisation that these policies could almost be begun afresh. African-American men are worse off economically than they were in the 1960s, and the energetic achievement of the first black presidency has been marred by an equal and opposite reaction.

Since the election of Trump, political science has tried to establish whether it is economic anxiety or racial animus that fuels his supporters. At first the answer seems obvious: when Trump warmed up his presidential run with the fraudulent accusation that Barack Obama was an African called Barry Soweto, it was not a tactic aimed at the hearts of the financially precarious. But the complex reality is that economic anxiety expresses itself through racial animus, and both find synergy in the punitive demonstrations of what is effectively an economic caste system. Perhaps most disturbingly, this social framework often requires no malice or even significant agency to operate (part of the reason why accusations of racism are received with such defensiveness).

Next page