Table of Contents

List of Illustrations

1. AC in the BBCs New York studio. (By kind permission of Nick Clarke/Orion)

2a. At the White House in 1941. (Photograph by Ralph Morse, reproduced by kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

2b. AC reviewing the troops along a line of New York City mounted police in the early 1960s. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

3a. AC in front of the general store in Cutchogue, Long Island. (Copyright Leonard McCombe/Time Life Pictures/Getty)

3b. AC drifts past a neighbours house at Nassau Point, Long Island. (Copyright Leonard McCombe/Time Life Pictures/Getty)

4a. AC filing a story to England from his teletype machine in Nassau Point. (Copyright Leonard McCombe/Time Life Pictures/Getty)

4b. AC with his son John in a New York studio. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

5a. Jane cutting ACs hair. (Copyright Leonard McCombe/Time Life Pictures/Getty)

5b. AC, Jane and Susie at 114 East 71st Street. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

6a. AC discussing the Hollywood film business with colleagues in 1949. (Copyright Peter Stockpole/Time Life Pictures/Getty)

6b. AC with long-time friend Lauren Bacall. (Copyright Nick de Morgoli/Camera Press, London)

7. AC discussing issues of the day with the man on the street. (Copyright Leonard McCombe/Time Life Pictures/Getty)

8a. AC with Jane aboard the Queen Mary. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

8b. AC delighted and relieved to be nearly home and back in New York. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

9. In the studio, 1970s. (Copyright Penny Tweedie)

10a. AC and President Eisenhower during the filming of General Eisenhower on the Military Churchill. (Courtesy of the Alistair Cooke Collection in the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

10b. AC with Attorney General Robert Kennedy. (Courtesy of the Alistair Cooke Collection in the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

11a. Adlai Stevensons 54th birthday. (Courtesy of the Alistair Cooke Collection in the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

11b. AC interviewing LBJ about Vietnam. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

12ac, 13ac. AC in his study at 1150 Fifth Avenue. (Copyright Penny Tweedie)

14a. AC putting in the long gallery at 1150 Fifth Avenue. (Copyright John Byrne Cooke)

14b. AC practising his swing in Central Park. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

14c. AC chipping out of a bunker at Islands End Golf & Country Club. (By kind permission of Alistair Cookes family)

14d. AC after a round with Bing Crosby and Robert Cameron. (Courtesy of the Alistair Cooke Collection in the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

15a. On the roof of 1150 Fifth Avenue, overlooking the reservoir. (Copyright Penny Tweedie)

15b. In the living room of 1150th Fifth Avenue. (Copyright Penny Tweedie)

16. Portrait by long-time friend Roddy McDowall. (Copyright Roddy McDowall courtesy of the Roddy McDowall Trust)

Introduction

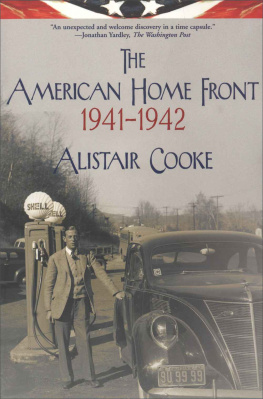

Alistair Cooke was the classic Anglo-American. He embodied the cultural and political bond that linked Britain and the United States during the long half century from the Second World War into the twentyfirst century. In the great game of current affairs, he was an observer, not a player. But like the best observers, he helped define the game.

My parents were ardent Americanophiles. As a result they would sit each week listening to Letter from America, like wartime refugees glued to a message from a land afar. Cooke kept them in touch with Strong America in the 1950s, Rich America in the 1960s, Questioning America in the 1970s and Uncertain America in the 1980s and 1990s. He never preached. He was accused of ignoring the dark side of American life, but his bias throughout was that of an East Coast liberal conservative. It was the bias of most of his British listeners.

Alistair Cookes writing was extraordinary. He wrote in conversation and he spoke in prose. In fifty-eight years of Letter from America he perfected the journalism of personal witness, adapting it brilliantly to the medium of radio. His mellifluous mid-Atlantic voice treated Britain and America as if they were two armchairs talking to each other, with the Pond as coffee table. Above all, he knew his craft. He never wrote a dull sentence. He never lost touch with narrative, with the commentator as storyteller, learned from his love of theatre and movies. He understood that listeners wanted more than the old standbys of anecdote and opinion. They craved context and history. As his years lengthened into decades, Cookes journalism acquired a depth inaccessible to younger practitioners.

Here was a man who could recall Hoover and Roosevelt. He could compare Churchill and Truman as orators, for he had heard them both. He could remember the arrival of air conditioning, the building of freeways, the exploding of the atom bomb and Bobby Jones making the green in one. His letters from America brought the New World into the drawing rooms of the Old, not as a series of sensational events but as a rounded culture. His journalism published and broadcast in the United States returned the compliment. It brought British culture to American attention. In periods when the two countries seemed at risk of tearing apart from each other, he linked hands and held them tight.

Cookes work and outlook were rooted in his past. He was born with the name of Alfred in 1908 in Salford, Lancashire. His father was a metalworker, Methodist lay preacher and teetotaller. His early theatrical and writing talent was noticed by his teachers, who encouraged him to a Cambridge scholarship. The upwardly mobile Cooke changed his Christian name to Alistair and applied himself furiously to acting, producing and writing. He founded The Mummers and edited Granta. By the age of twenty-two he was suggesting himself to the Manchester Guardian and the BBC as a contributor on theatre, poetry and literature. In 1932 he struck gold. He won a Harkness Fellowship to Yale and Harvard. The curtain opened on what seemed an even more glittering stage. For the drama of theatre he exchanged the drama of America.

Cookes early ambition was to become a leading theatre director. This ambition was cursed by his success in transatlantic journalism and the people he met thereby. He was taken up by another British refugee, Charlie Chaplin, and wrote scripts for him. Cooke married an American model, Ruth Emerson (a relative of Ralph Waldo), and moved back and forth between London and America in search of work, becoming the film critic for the BBC in 1934. He wrote a Letter from London for NBC, allegedly clocking up 40,000 words for American outlets at the time of the Abdication in 1936. Back in America, he suggested a similar venture in reverse, for the BBC. With the outbreak of war he risked his reputation on both sides of the Atlantic by taking out American citizenship, granted in 1941.

Cookes career in America was initially that of a normal foreign correspondent. In the 1940s he worked variously for The Times, the Daily Sketch and the Daily Herald. In 1940 he also began regular broadcasts for the BBC, titled American Letter (they became Letterfrom America

Next page