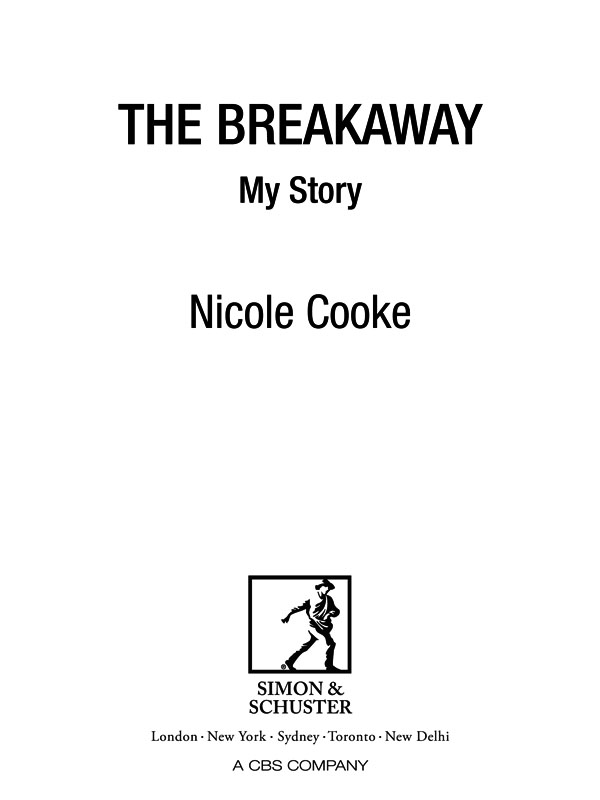

THE BREAKAWAY

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2014

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2014 by Nicole Cooke

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Nicole Cooke to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have inadvertently been overlooked, the publishers would be glad to hear from them and make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-47113-033-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-47113-036-6

Typeset in the UK by M Rules

Printed in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Foreword

by Graeme Obree

C ycling is a tough sport. To succeed in disciplines like the hour and road racing requires years of total dedication. Racing itself takes up little time but training, bike maintenance, sponsor duties and living the athletic life, with its diet and sleep requirements, leave little time for anything else. For male riders on professional teams, the training can be social and a rider can go out with a group of similar ability where there will be conversation to break the monotony of hours of graft. For male pros, there will be mechanics to clean and ready the bike for the next day of graft.

Nicole carved out her own path as a female British professional rider where the financial reward was little compared with her male counterparts and the graft would generally be done on her own. Each day required her to reach into herself to do her gruelling and monotonous training alone, driven only by her ambition and vision. Not only that, but a professional road cyclist faces the unavoidable and inevitable crash and injury scenario which only adds to the harshness of the sport. For a rider conducting the majority of their training alone, on the road, the risk of crashes and injury is multiplied. Nicole was no stranger to this and displayed amazing tenacity in coming back from injuries.

Today there is a fully Lottery-funded, military-style system. Not so in the days when Nicole first came to the fore. I remember meeting her briefly when she had her first successes in the early years. None of us could have foreseen the changes that would be made in both funding and approach. Unfortunately for Nicole, she probably started with one foot on the wrong side of change. Her articulate intelligence and lack of subservience would also single her out as dangerous to the emerging regime.

Then there was the gender issue. If Nicole had been born Nicholas and had achieved the exact same results in the male world, she would have been not just equal to, but elevated above both Mark Cavendish and Sir Bradley Wiggins. She was the youngest-ever winner of the Giro dItalia, in the fastest-ever time. She won the Tour de France. She won one-day classics such as the Amstel Gold Race, Flche Wallonne and Tour of Flanders. She won the World Cup. She won sprints, mountain-top finishes and broke away to win alone. She won green jerseys, polka dot jerseys and time-trials. In 2004, she didnt win the only womens road races that appeared on UK television, the Olympics and World Championships, because there was no British team worthy of that name to support her against other nations. Nevertheless, a string of silver and bronze medal positions bore witness to her talent and she was (and still is) the only British road rider to be ranked World No.1. Then in 2008, Nicole became the first-ever rider to win the Olympic and World road races in the same year. Unsurprisingly, she achieved this at the same time as the UK developed talent to provide some support for her.

The general attitudes that portray women in sport as second best, which in itself can lead to injustice and discrimination, were even on show when I was interviewed by Alastair Campbell for a series he was doing for The Times on the greatest sports figures of all time. When he asked me for my choice, and I named Jeannie Longo, he was clearly taken aback that I had chosen a woman, and a woman cyclist at that, given the fame and aura that surrounded male cyclists. Bear in mind that at the time Jeannie had not been implicated in drugs and Nicole would go on to achieve so much more. My argument that peer-group dominance made her pre-eminent did not convince him. I told him he was sexist, said he should also include Ellen MacArthur in his list of greats, and we moved on. This was not new, as I had witnessed both subtle and blatant sexism in the heart of the sport itself and in the media for a long time. In fairness, Alastair perhaps took my outburst to heart and later went on to write a good article in support of Nicole. Sadly, this issue is not merely historical and there is current debate about why there is no longer a womens Tour de France on the calendar. Road cycling remains hugely male-dominated, and achievements in womens sport in general go largely under-reported. When you add to that the huge disparity in sponsorship, funding and support, then you can begin to understand and sympathise with Nicoles story.

She was a trailblazer who forged a path that was clearly defined for the male riders, but equally she struggled to get womens cycling treated seriously in the UK, and there were many barriers placed in her way. Perhaps the most eloquent witness to those bruising encounters with a British establishment not willing to embrace the individual can be seen at the Manchester velodrome, which houses the headquarters of British Cycling. As you walk in from the entrance, there is a corridor packed with full-size portraits of GB stars Sir Chris Hoy, Victoria Pendleton CBE, Chris Newton, Rob Hayles and the rest. Visiting some years ago, I noticed that the achievements of both Nicole and myself were not worthy enough to elevate us to such company.

Nicole was the first female to join a continental team. She left home for Italy, aged 18, with a minimal grasp of the language, and was on her way. Like my own experiences, it was not long before she was exposed to the dark world of drug abuse that pervaded road cycling. Her accounts of dealing with this are engrossing. Despite this, she was still able to produce the results that she did. One such performance touched me and even changed my own perspective. I was watching live on TV when in a wet, uphill finish, coming from behind, all hope momentarily lost, she powered to win the Olympic road race. I had that instant wow feeling and a tear in my eye for the first time ever after a sporting performance. Knowing Nicole personally, and knowing the honourable and genuinely nice person she is, made this possible. People told me over the years how I had that same effect on them when I was racing but only now, 15 years later, and thanks to Nicole, could I feel it for myself. Here is a remarkable story: one young girl doing it her own way and getting to heights never dreamed of by British Cycling. Afterwards came the British men on the road. This is the story of the events that preceded those exploits and were necessary for those later successes. I can only hope that a spark of change can happen around gender inequality in the sport, as a consequence of Nicoles amazing contribution to enlightenment.