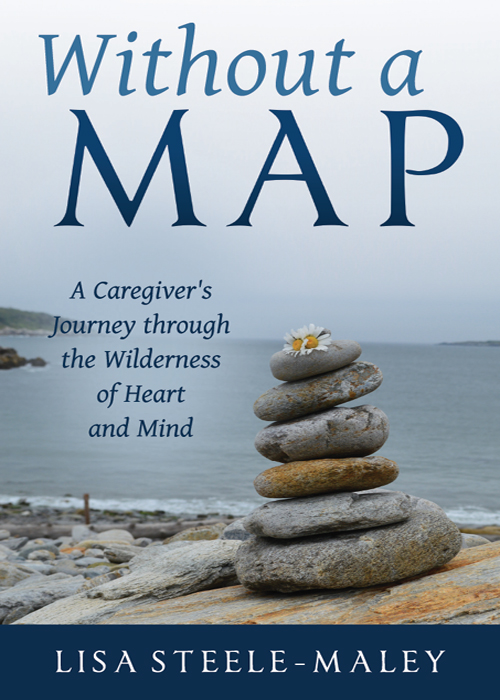

Copyright 2018

by Lisa Steele-Maley

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work in any form whatsoever, without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief passages used in connection with a review.

Some names and identifying details have been changed

to protect the privacy of individuals.

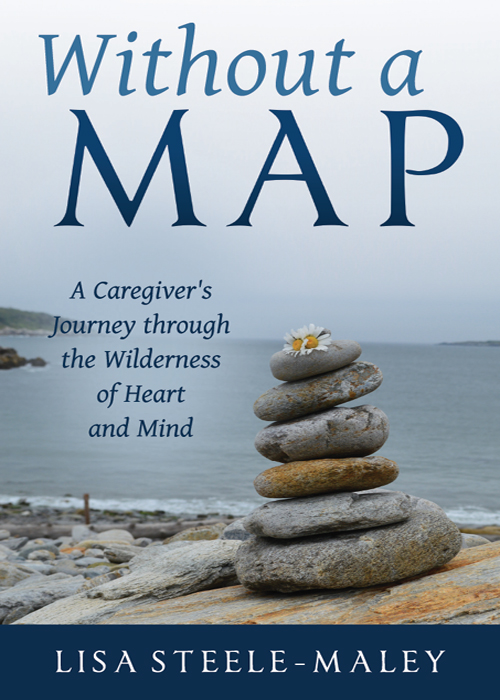

Cover design by Frame25 Productions

Cover art by Duncan Steele-Maley

Interior design by Howie Severson/Fortuitous

Turning Stone Press

8301 Broadway St., Suite 219

San Antonio, TX 78209

turningstonepress.com

Library of Congress Control Number

is available upon request.

ISBN 978-1-61852-122-4

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

Dedicated to my family

and to the grace that awakens in the

heart of giving and receiving

Disclaimer

This is my true story. The people and events described here are real, as are the worries, questions, joys, sorrows, and other emotions they evoked.

With respect, I have changed the names of the doctors and the residential living facility to protect professional privacy.

With appreciation, I have used my family members' real names. At different times and in different ways, they offered support, advice, presence, and vital companionship. Their experience of these events will be different from mine; I am grateful for their permission to share my perspective.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Over the course of five years, my father succumbed to progressive dementia. As my family navigated the uncharted territory of supporting him, I was surprised over and over again by how hard the process was and by how much there is yet to understand about dementing illnesses. I scoured the library and the internet for information and guidance. Some of what I read helped to explain what was happening medically and some shed light on what the experience might be like from my dad's perspective. Some resources offered a range of possible conditions that could be causing his dementia and sketched out the likely progression ahead. They were helpful, but they were not enough. I craved clarity and answers. I wanted a map.

I have spent most of my adult life traveling in the wilderness. Although I always carry a map, I never really know exactly what to expect. A map provides landmarks and guideposts that offer comfort and perspective, but a trip carefully planned while consulting the contours and promises of a map will always adapt to a myriad of unknown variables. In this case, there was not even a mapand I definitely did not know what to expect. Dad's situation and condition were, by their nature, unpredictable. Furthermore, no two people are the same and, of course, there is no right way to travel life's path. There is no wrong way either. In Speaking Our Minds, Lisa Snyder writes, A personal definition of Alzheimer's is as varied as the disease itselfas unique as the particular course it runs in each person who has it. While Dad was never diagnosed with Alzheimer's while he was alive, Snyder's description resonated with my sense that we would not find any clear answers by looking out into the world. We needed to find our way on our own.

I took solace in knowing that, while Dad's path was solely his, he did not need to travel it alone. That is, in fact, the only thing I had to go on as I became his primary caregiver. I could ensure appropriate autonomy and care and provide companionship and joy while he followed an otherwise very lonely and isolating trail. When I fell into step with my dad's journey with dementia, I did not have any idea where we were going, how we would get there, or what we would encounter. But we would travel together with attention to the moments that would arise along the way.

Even now as I recall the steps of our journey from beginning to end, I cannot chart this wilderness for anyone else. I can only cast a flashlight beam down the dark path, shining light on pieces of our story as comfort and company for other families navigating the twists and turns of their own caregiving landscape.

1

Without a Map

Adapting to a Changing Life

T hroughout my twenties and thirties, as I embraced the responsibilities of adulthood, I navigated the literal wildernesses of the earth, deeply immersed in the biology of North America and my own body. I hiked, kayaked, and canoed through the northern United States and Alaska. I met my future husband, Thomas, on the trail. We built and repaired trails high in the mountains and deep in forests. Working with teens and young adults, we matched the rhythms of our lives to the flow and demands of the landscape. Living in community and working hard both strengthened and broadened our bodies, minds, and hearts. The roots of our lives grew long and strong, stretching deep into the earth and reaching out to one another. From these interconnected roots, Thomas and I would grow into our future together.

During our early years in Alaska, we became careful wilderness travelers. We relished the detailed planning of a route, studying maps for days before a trip. We organized menus to ensure that we had plenty of food but not too much weight to carry. Most importantly, after all of our careful preparations, when we stepped onto the trail at the beginning of a trip, we set aside all expectations and intentions. We were ready to meet whatever blessings or challenges arose along the way.

A few years after we met, Thomas and I spent a summer working on a trail maintenance crew for a remote Forest Service ranger district. Each week we traveled to and from our work sites by boat or floatplane. Traveling by plane was an exercise in precision, patience, and acceptance. We had to pack precisely to be within the plane's weight limits while also having the tools, fuel, and food we needed for the trip. We transported only the tools we anticipated needing for a project and no more, but we always packed an extra day's worth of food in case weather kept the plane from picking us up on schedule. After all of our careful attention to detail, we remained at the mercy of many elements beyond our control. We spent quite a few Monday mornings scrambling to get ready for our departure only to sit at the airport for hours waiting for the fog to lift enough for takeoff.

One week our crew was scheduled to do trail maintenance at a lake nestled high in the mountains. Our flight in was smooth, tucked between the morning's late-clearing fog and the afternoon's early storms. We unloaded quickly so the pilot could take off again before the clouds closed in on the narrow lake basin. As he flew off, we turned from the beach to haul our things up to the cabin that would be our base for the week and slowly absorbed our situation. The dense forest was cool and dark, there were bear tracks and scat everywhere, and the deep grooves and long, coarse hair in the cabin siding made it clear that our shelter had been used recently as a scratching post. We had been cohabitating with brown bears all summer, but something about this place felt differentnot necessarily unsafe but definitely unpredictable. A feeling of unease settled into our bones that afternoon and remained with us all week. The dense understory of the forest, finicky mountain weather, and isolation of this camp were constant reminders that there were more elements outside of our sight and control than within it.

Next page

1

1